Leonard Maidment: missing, found, now remembered

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Leonard Maidment: missing, found, now remembered

As Serjeant Leonard Maidment nervously waited in the pre-dawn gloom of the morning of 20 July 1918 preparing for his first combat on the Western Front, his thoughts would have turned to his family, safe at home in Andover. His father, Edward and mother, Bessie would be oblivious to the fact that Leonard’s battalion, the 2/4th Hampshire Regiment, was – along with other battalions – about to launch an attack on the Germans who had recently broken through French lines just west of Reims.

He no doubt thought also of his older brothers and sisters Edward, Walter, Henry, Louisa and Bessie. Dorothy and Florence were younger than Leonard (who was 22) with Frederick the ‘baby’ of the family at thirteen. Leonard probably reflected on how he came to be here, on the densely wooded slopes just north of Epernay. Compared to many, he had had a relatively safe war. A pre-war territorial, he had – on the outbreak of the war – immediately volunteered for overseas service.

Rather than being sent to France, his battalion, the 1/4th Hampshires, was – along with many other local territorial units – sent to India where he had arrived in November 1914. Subsequently posted to the 2/4th Battalion and promoted to serjeant, he had seen action in Palestine during 1917 before being ordered to France in the spring of 1918.

Men of the Black Watch (Royal Highlanders) 2nd Battalion, practise marksmanship across sandbag defences on the coast near Arsuf. © IWM (Q 12485)

Up to this point the 2/4th had lost no more than 60 men killed or died of disease. He was in no doubt that this was about to change.

It was only a few weeks ago, in early June, that his battalion had joined the 62nd (West Riding) Division near Bucquoy, just south of Arras. By the 10th of the month the first men from the Hampshires were receiving instruction in trench warfare from the veterans of the Duke of Wellington’s (West Riding) Regiment.

Unlike Leonard and his comrades in the 2/4th Hampshires, most of the men of the 62nd (West Riding) Division had seen plenty of action in the last year or so. Despite the almost impenetrable Yorkshire dialect of some of his new comrades, he had chatted to men who talked about Beaumont Hamel, Bullecourt, Lagnicourt, Havrincourt and Bucquoy. Although eight months ago, these Yorkshiremen seemed most proud of their efforts at Havrincourt and the subsequent dreadful fighting at Bourlon Wood. They had talked about advancing alongside “Harper’s Duds”, the affectionate name for the 51st (Highland) Division. Even though the Highlanders had been held up at Flesquières, they were pleased to be alongside the Scotsmen again, here in the wooded hills of the Bois de Reims.

Above: Battle of Tardenois. Men of the 6th Battalion, Black Watch (51st Division) about to encamp in woods near St. Imoges after the capture of the Bois de l'Aulnay, 25 July 1918. They were just relieved by the French. Note the young age of the soldier in the left middle foreground, almost certainly underaged. © IWM Q 11093

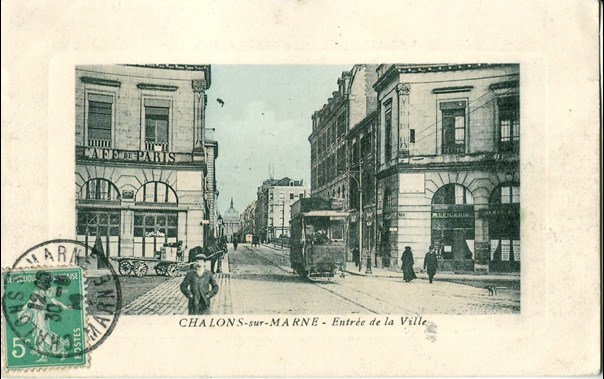

The minutes slowly ticked by. As the artillery barrage thundered overhead, Leonard recalled the highs and lows of the last few days. Urgent orders to march to a railway station at Mondicourt, east of the town of Doullens, had been received and on Sunday 14 July the long journey south by rail had started. Even though they were cramped into uncomfortable goods carriages (40 men or eight horses according to the sign on the side of the truck), the journey had been interesting. They had travelled via Amiens, Beauvais, Paris, Montereau and St Florentin. Nearly two days later they had clambered off the train at Sommesous and into lorries which had taken them to billets at Recy, close to Châlons-sur-Marne on Tuesday 16 July.

An early start on Wednesday 17 July had seen them marching along dusty French roads in the broiling heat of the French summer. Although this was the Champagne area, there had been precious little time to enjoy any of this particular type of wine. Leonard remembered the villages along the way, including Matouges and Jalons where they had been warmly greeted by the inhabitants. Eventually they had arrived in Athis where they took up billets and spent the night, during which a severe thunderstorm had occurred.

They had had a restful day on Thursday, there had even been a battalion band playing in the village during the day, much to the enjoyment of troops and locals alike. This short period of pleasure could not last and the following morning (Friday, 19 July) the battalion had marched off into the forest. It had been a short march - just 11 miles - and they had reached their destination of Germaine by mid-morning. Leonard had seen the battalion Commanding Officer, Lt-Col Brook, and the company commanders move off during the afternoon to reconnoitre the next stage of the march to Courtagnon. The officers had returned from their reconnaissance and at around midnight the battalion had set off even deeper into the massive forest.

The last leg of the march had been dreadful. It has seemed like chaos, the babble of voices in French and Italian had been mixed with the occasional explosion of German shells. There had been no light and the overgrown forest seemed dark and sinister. The line of men struggled along narrow, crowded tracks and they had frequently halted then surged forward, only to halt again. Tired, and behind schedule, they had made it to the correct place at the North East corner of the Bois de Courtagnon. The battalion’s officers were unhappy, they were being asked to launch an attack against the Germans with virtually no notice and across ground that was totally unfamiliar. They were also reliant on French Artillery. Although efficient, would ad-hoc coordination work? Despite this, they were being told that the Germans had bitten off more than they could chew and a successful attack up the valley of the Ardre would mean the Germans would be pushed back to Bligny, and once there, the Montagne de Bligny could be cleared and the Germans would be really on the back foot.

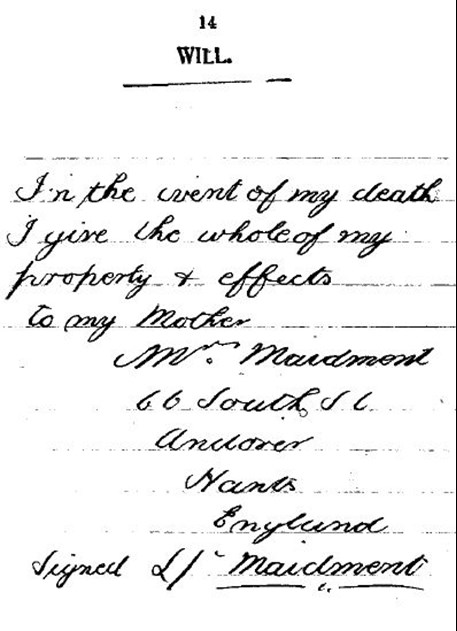

It was now fully light, and another gloriously hot and sunny day was in prospect. Leonard looked at his watch. It told him that it was 7.30am: half an hour to zero hour. Thankfully his battalion, and the two Duke of Wellingtons battalions in his brigade were in support, and not due to go in with the first attack. For the umpteenth time, Leonard checked his rifle and other equipment. He could see the men of his platoon doing the same thing. Anything to try to relieve the tension. How many would be alive at the end of the day. Would he be alive? He had made out his will, and it was in his pocket book.

At 8am ‘Zero Hour’ - Leonard would have heard the crescendo of the artillery and supporting arms. Battalions of the 62nd (West Riding) and 51st (Highland) Divisions went forward, launching the attack with French and Italian troops on either side. It was a truly international effort.

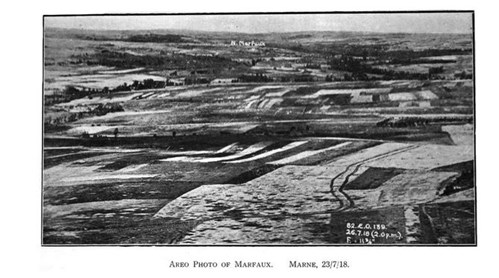

The Hampshires moved forward from their supporting positions, flanked by the 2/4th Duke of Wellingtons and the 5th Duke of Wellingtons. Heavy German artillery fire came down. In front of them, battalions of the West Yorkshire Regiment attacked towards the villages of Marfaux and Cuitron.

“Surely,” said an officer, “there was no war there was no war in this pleasant country.” But the standing crops in the undulating valley, the vineyards on the slopes leading up to the heights and the dense woods along the ridges, concealed from view hostile positions of great strength, and death lurked in the shimmering haze covering those peaceful fields and quiet uplands.

The Story of the 62nd (West Riding) Division 1914-1919, Volume 1, Everard Wyrall. (Undated Publication: John Lane, The Bodley Head, London.)

The West Yorkshires attack stalled. The artillery barrage had fallen too far ahead and fire from the German machine gun nests (located in the villages and wooded slopes above the villages) swept across the open fields. The West Yorkshires dug in just in front of Marfaux, still under a withering fire.

As the Hampshires moved forward from their positions behind the front line they received orders to reinforce the West Yorkshire battalions. Lt Col Brook instructed ‘B’ and ‘D’ Companies, with ‘A’ Company in support, to continue the attempted advance on Marfaux.

Into this maelstrom stepped Leonard…

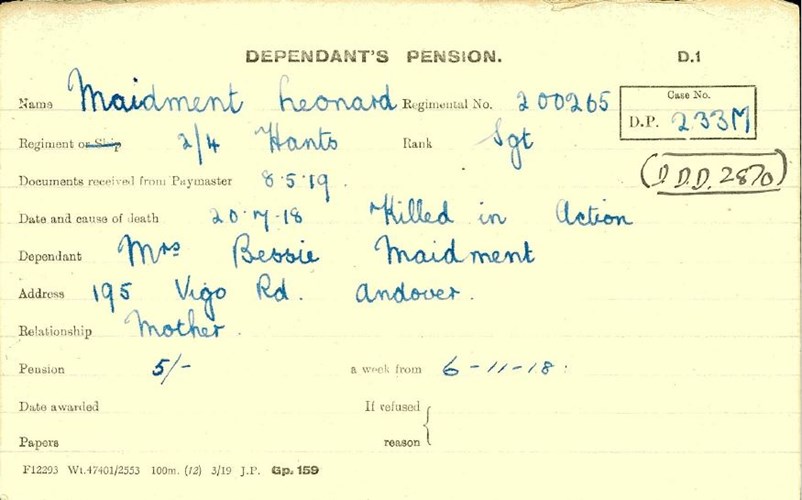

Back in Andover, Mr and Mrs Maidment received the dreaded telegram. Leonard had been killed in action on 20 July. Later they learned that his body had been lost and he had no known grave. His name was therefore listed on the Soissons Memorial to the Missing. Like so many other families, they had no grave to visit, nowhere to focus their grief. All they had was a pension of 5/- per week. As the years rolled by, some of the family moved to Australia.

Above: Battle of Tardenois. Soldier of the 2/4th Battalion, Hampshire Regiment (62nd Division) looking at the recent graves of three Germans. Bois de Reims, 24 July 1918. © IWM (Q 11091)

* * * * *

In 2004 I visited Marfaux British Cemetery with my wife. As I walked between the headstones, I came across one that caught my attention. This headstone marked the grave of an “unknown” Serjeant of the Hampshire Regiment killed on 20 July 1918.

It is not uncommon for one or even two of these extra details to be included, but for all three to be provided is somewhat unusual. Knowing that only one battalion of the Hampshire Regiment had been in the area on 20 July 1918, I thought that this may be worthwhile following up when we were back home. So it proved. Only two serjeants of the Hampshire Regiment were killed on this date, one was killed in what is now Iran, the other was 200265, Serjeant Leonard Maidment who was named on the Soissons Memorial to the Missing.

After writing to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, who kindly pointed me in the right direction, the Joint Casualty and Compassionate Centre (JCCC) of the Service Personnel and Veterans Agency (SPVA) confirmed in November 2009 that grave 3 in Row G of plot III could only be that of Leonard Maidment. They did, however, want to try to trace his family prior to the headstone being replaced.

In February 2012 I received an email from Keith Maidment in Australia who was researching his family tree. Leonard was his Great Uncle (Leonard’s brother, Henry, being Keith’s grandfather). Since then, we have been in discussion and Keith, in conjunction with the mayor of Marfaux, the SPVA, the CWGC and the Hampshire Regiment, has arranged for a service to take place at Marfaux British Cemetery on 20 August. This will be the first time that any of his family had had the opportunity to pay their respects at Leonard’s graveside.

Ninety Five years after his death, Leonard is now no longer missing.

Article by David Tattersfield

Related article: The Day my Family Came

Further reading

Further images are on the WFA's Flickr account