The Abandoned St Quentin Memorial to the Missing

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Abandoned St Quentin Memorial to the Missing

In 1926 the French government raised serious concern at the number of free-standing memorials being proposed by the Imperial War Graves Commission (IWGC) to honour the missing and among those to be sacrificed would be the one planned for St Quentin.

It was a challenge to create the necessary number of structures to carry the many names of the missing.

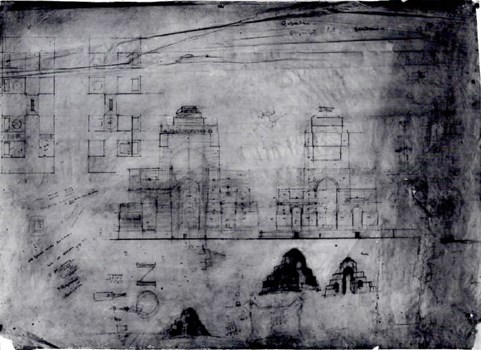

Reproduced here is a 1923 pencil and crayon sketch by Edwin Lutyens of the St Quentin memorial, and the similarities are clearly striking between this memorial and what would go on to appear as the memorial to the missing of the Somme at Thiepval, complete with its complex and distinctive interlocking arches.

The drawing of the St Quentin Memorial held in British Architectural Library, RLBA , London.

The architectural similarities were not lost on Bulletin editor James Brazier when he came across the drawing in the British Architectural Library in London in 1999, and it enabled him to provide another layer of insight into a complex issue.

Debate about the free-standing memorials to the missing had come to the fore among the WFA faithful in 1999; this after a letter had been reproduced in the Bulletin that had been sent in 1929 by the IWGC to the father of a Private Archibald Payne (18912) – a soldier killed in action on 1 July 1916 whilst serving with the 1st Battalion of the Hampshire Regiment on the Redan Ridge.

The letter said that Private Payne's name had originally been down to be inscribed on the St Quentin Memorial to the Missing, but that his name was now going to be inscribed instead on what was to be known officially as the ‘Thiepval Memorial’.

The Thiepval Memorial that replaced the St Quentin scheme, but was clearly forged from the same architectural template.

Putting the content of this letter together with the Lutyens’ sketch, the evidence was now clear that one of the most striking commemorative landmarks of the war had originally been designed for St Quentin – albeit with some minor adaptations, such as the loss of the domed top depicted on the St Quentin sketch.

This in itself was not wholly surprising, as it had long been known that a number of additional memorials to the missing had been planned for the whole of the Western Front. Indeed, some researchers had previously suggested that the Thiepval Memorial had originally been designed to straddle the Albert-Bapaume Road at Pozieres.

Lutyens' design for the St Quentin Memorial had been approved “with acclamation” by the IWGC in early December 1924. However, it had been decided at a meeting in Paris of the Anglo-French Mixed Committee in June 1926 that this memorial, along with four others, be abandoned. Lutyens was then commissioned to design the Thiepval Memorial, and clearly decided to adapt his previously acclaimed design for St Quentin to fulfil the new remit.

The Thiepval Memorial would be formally unveiled by the Prince of Wales on 1 August 1932 and became the fourth free-standing memorial to the missing in France, with the others at Soissons, La Ferte-sous-Jouarre and Neuve-Chapelle.

The inauguration of the Thiepval Memorial in 1932 © Commonwealth War Graves Commission

According to extensive research by Major and Mrs Holt, plans for other free-standing memorials at Lille, Cambrai, Pozieres and Bethune had also been dropped alongside the St Quentin scheme, and the names of the missing they were to hold allocated to memorial walls in IWGC cemeteries instead.

Extra land had been obtained at Ploegsteert to take the names that had been destined for Lille, Louverval took the Cambrai names, Loos the Bethune names, while Pozieres, Le Touret and Visen-Artois were redesigned to accommodate the others which were also to be shared with the St Quentin names on the new Thiepval Memorial. It was also decided at the same time that the memorial proposed in the Faubourg d'Amiens cemetery in Arras should be changed to take the names of the missing of the Royal Air Force.

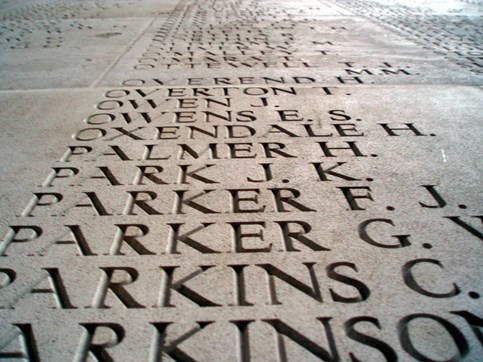

In Flanders, the Menin Gate proved unable to cope with all of the names of the missing and a memorial wall had to be built at Tyne Cot to accommodate those that had been lost after 15 August 1917. Even that was to prove insufficient and further names would be recorded at Ploegsteert, while the names of many of the Dominion forces would be commemorated at their own memorials across the Western Front.

Edited by Dr Martin Purdy