The Final Whistle: Rosslyn Park - a Rugby Club at War

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Final Whistle: Rosslyn Park - a Rugby Club at War

This is the story of fifteen men and more from one London rugby club who answered the call to arms in the Great War; they did not live to hear the final whistle that ended the game. Their history begins with their names lost in mystery. Rosslyn Park Rugby Club was established in 1879, the year that some British soldiers died and others won Victoria Crosses at Rorke's Drift in South Africa. They also fought and died in Afghanistan, as they do again in the twenty-first century. For relaxation they played rugby, with rudimentary pitch and posts. In 2007, Prince Harry kicked an oval ball about with his Household Cavalry unit in Helmand Province, Afghanistan. These colour images now flash worldwide on the web and satellite television - our technology has progressed if perhaps our civilisation hasn't.

From red and white hoops into khaki

In 1914, with a new war looming, Rosslyn Park, then playing in Henry VIII's ancient Deer Park in Richmond, south-west London, already had thirty-five seasons of mud on its shorts; successive waves of players had worn its red-and-white hooped jersey and would now don khaki. Any club of young, physically fit men will naturally suffer losses in wartime; those killed in the ‘Second Great War' of the century, including Prince Alex Obolensky, a flying winger killed in his RAF Hurricane in 1940, are rightly revered on a clubhouse plaque. But why is there no memorial to its Great War dead? Was it somehow lost in the move from Richmond to a new ground in Roehampton in 1956? A few short miles but a careless slip by clumsy movers and a slab of broken marble consigned in muttering embarrassment to a skip; without a memorial, there was no Roll of Honour, no record of the club's pain and pride.

So began the first work to piece together the list of men who died. The sole clue was a yellowed press report of the Club's 1919 Annual General Meeting, reporting sixty-six members killed and six ‘missing', but no names. Thankfully the club's membership records survive: the meticulous copperplate entries for name, address and (occasionally) school attended were checked against Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) online records of those who died. Some took hours' more trawling through Census, school and university records, newspaper microfiche, war diaries, regimental histories and National Archives to achieve conclusive matches. The total has already surpassed the stated seventy-two and currently stands at eighty-five; several more sit ‘on the bench' - tantalisingly short of the perfect match of name, address or initial that would select them definitively for the side lost to history.

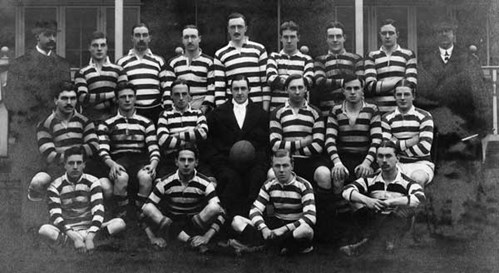

1) Rosslyn Park's 1909-10 XV; six would die in the war

Long hours in libraries will be familiar to any researcher - the hard yards have to be won. But this project was frequently illuminated by chance discovery when helpful correspondents flashed the light of their insight over the internet. One early enigma was J.E.C. Bodenham, who joined the Club in 1913 and is found on the Thiepval Memorial, a first-day casualty on the Somme. He was a rifleman in the 1/16 London Regiment (Queen's Westminster Rifles).

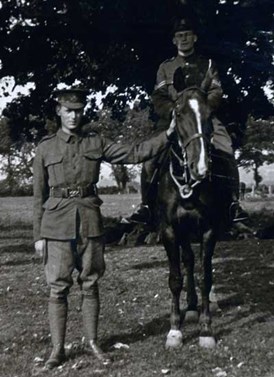

2) Jack Bodenham, 1/16 London (QWR) in Richmond Park

His CWGC entry does not tell us much, and his status in the ranks did not promise a well-documented trail. Yet why, in a middle-class dominated sport, was the proud possessor of three initials (J.E.C.) the only club member not to take the King's commission? The answer came via an intervention by a reader of the website where the early research was collected and published: ‘J.E.C.' emerged as John Edward Cyril Bodenham, of Ratcliffe and Ampleforth College, one of sixteen children in a prosperous Catholic family, whose famous fragrance business still flourishes today. Further enquiries to descendants brought forth his unpublished diary and letters, written up until the night of 29 June 1916 and the postponement of the battle in which he would lose his life. They reveal a touching story of a sensitive and intelligent soldier, contentedly unburdened by the weight of command.

Many names were already linked through shared friendships at school and university. In varying permutations, they bob to the surface time and again in a stream of match reports, school magazine articles, team-sheets and photograph captions. The Club would unite them again - friends naturally flock together in rugby - and prolong those masculine bonds into adult life. So, fleetingly, would military service in war, until it tore their brief lives and friendships violently apart. In their hour of dying their median age will be 23.

Two close friends from Durham School, Jimmy Dingle and Nowell Oxland - both vicar's sons - can be tracked through their school lives and rugby careers at Oxford University and various London clubs to their deaths near Suvla Bay, Gallipoli in August 1915, separated by ten days and a few hundred yards. Oxland, 6/Border, achieves a posthumous distinction as war poet from his much-anthologised poem ‘Outward Bound' and is the only one of the Rosslyn Park peninsular dead to have a known resting place. His friend Dingle, an English rugby international with 6/East Yorkshires (Pioneers), is on the Helles Memorial. His campaign and death are closely documented in letters, witness statements, war diary and - somehow ironically - an epic poem written in captivity by fellow officer Lieutenant John Still. Both tales reveal the confusion and mismanagement of the Gallipoli expedition.

3) Jimmy Dingle, 6/EYR, England centre, died Gallipoli

Drawn together

Young men, whether from Australian outback, Indian railway or industrial Wales, were drawn by education or profession to London's metropolis and found companionship there with like-minded rugby players: they became team-mates and close friends. Syd Burdekin, an Australian from a notable Sydney family, could not wait for the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) and sailed for Britain to join the Royal Field Artillery (RFA).

4) Syd Burdekin

While many of his schoolmates perished at Gallipoli, he would die at Loos with his Trench Mortar battery. Another Australian, Eric Fairbairn, hailed from a Melbourne dynasty as famous for its rowing exploits as for its business acumen. Whilst at Cambridge, he won a silver Olympic medal for Great Britain, and competed in regular rivalry with a Belgian club from Ghent. When the call to defend ‘poor little Belgium' came he was quick to join up, yet died with the 10/DLI six days after reaching the front.

5) Flt Lt Jack Harman, killed nightflying on Zeppelin watch over Lincolnshire in 1917

Other players swim in and out of focus in the research into their lives. Arthur Tulloch Cull was born in Colombo, Ceylon, one of two sons of a charismatic school principal. He was Head Boy at Uppingham and surely destined for a life of leadership, although the school's alumni records note him only as a ‘Bank official'. He joined the Inns of Court Officer Training Corps, then the Seaforth Highlanders, but in January 1916 transferred to the Royal Flying Corps (RFC), inspired perhaps by his brother John who won the DSO in the 1915 attack on the Koenigsberg in Tanganyika. Arthur himself was killed on 11 May 1917 on offensive patrol east of Arras by one of Richtofen's Jagdstaffel 11 fliers; there is still considerable debate as to whether it was Karl or Wilhelm Allmenroeder, or even Lothar von Richtofen, the Baron's brother. Cull's name appears on the Arras Flying Services memorial to those with no known grave.

Yet does his story have a further unexpected richness? Is he the same A. Tulloch Cull, who in 1913 published a volume of infatuated poetry in praise of the ballerina Anna Pavlova? In a foreword she ‘accepts the dedication with pleasure'; a copy was in Rudolf Valentino's possession on his death. This rare book, consulted at the British Library, carries no confirmatory clue to the author's identity, although this most unusual of names surely suggest they are the same man. One central section of twelve besotted poems reveals his frustration that in 1912 he is required to be far away in Egypt, rather than witnessing La Pavlova's new show opening at the Palace Theatre, London. From the Club records of his given address it emerges that his employer was the Imperial Ottoman Bank in London. In 1912 the Khedivate of Egypt was an autonomous vassal state of the Ottoman Empire, but since 1882 had been under the increasing influence of the British. What exactly was Arthur's business in Egypt in 1912? Alongside hints that his father's latter days were scandalously ‘intemperate' and his end ‘pathetically inglorious', Arthur Cull the rugby-playing international banker and balletomane pilot killed in a dogfight remains a complex mystery.

6) Poetry by A Tulloch Cull RFC

They were not all young men. The career soldier from the famous artistic family, Guy du Maurier, first played for the Club in its earliest North London incarnation, when just sixteen in 1881; he became the oldest member to die as Lieutenant Colonel, 3/Fusiliers at Kemmel, aged 49, in 1915. Alec Todd, a gregarious British Lions rugby tourist to South Africa in 1896, also fought there in the Boer War, where wounds ended his England playing career. In 1914, the successful wine-merchant returned to the colours with the Norfolks and was killed at Hill 60, a day after returning from leave, at the age of 41. Oddly, he is both buried at Poperinghe and recorded on the Menin Gate.

7) Capt A F Todd, Norfolk Regt in France 1914

Much younger men than Guy and Alec were looking forward to a new rugby season and a life of promise when war broke out: the youngest, Gerald David Lomax, whose father was killed at Driefontein when he was just five years old, died of wounds suffered at Fromelles, at just 20 years of age.

Perhaps these players had absorbed some martial spirit from the terroir of Richmond Old Deer Park, in the manner of fine French wines. The ‘splendidly quick-drying springy turf' (1) had once been used as an archery range by warrior-Queen Elizabeth, that ‘weak and feeble woman, with the heart and stomach of a king.' On the second day of the war the writer Henry James could write privately of ‘the plunge of civilisation into this abyss of blood and darkness' (2); public hubbub, on the other hand, was of heroic adventure. The early clashes, roared on by armchair spectators reading sanitized match reports from the battlefield, had the flavour of one huge game. Plucky defence to the last man against superior opposition, defiant goal-line stands and, in true sporting headline fashion, the ‘Race to the Sea', as both sides attempted to outflank the opposition by running wide around the wings.

A series of last-ditch tackles, at the cost of thousands dead and wounded, stopped every attack until the Germans were squeezed out of play at the topographic touchlines of the North Sea and Swiss border. Both sides then settled down to a full-frontal forwards game in the mud, rolling on interminable replacements as men went off injured and dying. The thoroughbreds were forever left in reserve, starved of action, waiting for the opportunity to burst through a gap in the opposition line which, in those four hard years, only appeared very late as its German defenders died on their feet - or surrendered on their knees.

Global game

But the stark image of the Western Front is only part of the story. Just as these fresh recruits came from all corners of Britain and the Empire for trial on the rugby field, so they were sent out to fight in every theatre of this war. What emerges from the lives of these rugby men is a remarkable history in miniature of the entire war, across all fronts, arms, theatres and engagements. This Great War was, after all, the first world war: Rosslyn Park players from London died in France, Belgium Mesopotamia, Turkey, Palestine, Egypt and Italy.

Some went to ‘quiet shows' that proved just as deadly as the celebrated set-pieces of Ypres and the Somme. Second Lieutenant Guy Vickery Pinfield, stationed in Dublin with a reserve cavalry training unit, would be the first British soldier to die in the Easter Rising of April 1916, at the gates of Dublin Castle. Despite Ireland being a British ‘home front', his hastily buried body was never reclaimed by his family. He remained lost until its accidental rediscovery in 1963 and reburial in Grangegorman military cemetery. Jack Harman returned from plantations in Ceylon to join the ASC and served at Gallipoli and Salonika before joining 33 Squadron Home Defence flying against Zeppelins in Lincolnshire. He was killed in a night-flying accident at Hibaldstow in November 1917.

In a reminder that enemy fire was not the only wartime killer, some of these fit and muscular rugby bodies were tackled low by illness and disease in the field. Captain John Lloyd Jones of 2/Yorkshire Regiment, a former solicitor, was brave enough to be twice mentioned in Despatches and win the Military Cross (MC), but could not fight his own human frailty; he was wounded in August 1915, but died at home in North Wales of septicaemia and pleurisy in 1916. Naval surgeon John Rutherford, a Barts trained doctor, treated the wounded at Gallipoli on board HMS Theseus, stayed on in the Aegean and succumbed to tuberculosis in 1917. Another Gallipoli medic, Wellesley Roe Allen, RAMC never returned from Cairo where he died of sickness.

Even after the Armistice, when the killing had stopped, the dying went on: Herbert de la Cour of the Royal North Devon Hussars, was wounded a month before the war ended, but struggled on, paralysed and fighting infection, for another fourteen months before his eventual death in St. Georges Hospital, London. Sadder still, John Spread Beamish, son of an Admiral, was wounded in the leg at Railway Wood in May 1915, but took his own life while on leave recuperating. His death on the Harrow Road, a revolver by his side, is reported in The Times, sandwiched between the opening meet of the Bramham Moor Hunt and a hunting accident in Berwickshire.(3)

Some were honoured for their bravery, with Lieutenant Commander Arthur Leyland Harrison, another pre-war England rugby international, posthumously awarded the nation's highest award for his heroism at Zeebrugge in April 1918. Welshman Second Lieutenant Charles Button, RFA, also won honour from another nation when he and his 5/Battery, 45 Brigade were awarded the Croix de Guerre on the Aisne in May 1918. Button died as his battery was overrun by the German stormtrooper offensive, an action immortalised in oils by Terence Cuneo.

8) The Last Stand of the Gibraltar Battery, by Terence Cuneo

But far more fought in obscurity, their feats of arms rarely recorded and their death in ‘some corner of a foreign field' marked only by the marginal notes of overworked War Office clerks. Not for them the gleam of the Military or Victoria Cross, or even the dignity of a named grave, only the shadow of the Cross of Sacrifice or granite memorial.

Some inherent quality of bravery or natural leadership saw many rugby men take the lead, as they had on the field, whether as reckless pilots in frail biplane or balloon, as officers of doomed infantry companies or at the head of desperate naval storming parties. Youthful hopes - the promise of life, adventure, love - turned swiftly to fears of death, dismemberment, squalor and insanity. In callous mockery of the club motto, fortune did not always favour the brave. Charles George Gordon Bayly, named after his great-uncle General Gordon of Khartoum, followed the career path of his illustrious relative through Woolwich and Chatham, before learning to fly. His 5 Squadron RFC immediately flew to Maubeuge on the outbreak of war and his plane was brought down by ground fire on 22 August: his charred body in its RFC tunic was the first evidence to the advancing German commander that Britain was in the war. Bayly, a St. Paul's scholar and scrum-half was the first Club member and first British Army officer to be killed under (or over) enemy fire in the Great War. There would be many more.

9) Charles Bayly's charred body, the first sign that Britain was in the war

Their names are now scattered on public war memorials: in home towns where they lived and were loved, and on battlefields where they perished. They were also engraved on the rim of the Victory Medal, the circular bronze ‘Death Penny' and printed scroll from the King. But these are invariably scattered or lost. I have been privileged to view the plaque and medal trio of ‘first-class rugby forward' Arnold Huckett, killed on a terrible August night for 5/Wiltshires at Sari Bair on Gallipoli, touchingly reunited by a collector with those of his brother Oliver, killed in France. Syd Burdekin's medals are safe in a Sydney museum. As for the rest, who knows?

For many parents, the loss of a young son (or two, even three), heartbreaking in its own right, could also mean the death of the family name, as the male lineage was violently severed. It could be said that whole families died at Ypres, Suvla Bay or Kut. Kipling borrowed from Ecclesiasticus to promise that ‘Their Name Liveth for Evermore', but with no descendants to preserve them, the living stories behind those dead names have rarely been handed down. Nor are they collected in one place that unites them, as the rugby club once did. Occasionally photographs emerge from family albums that speak more eloquently than the formal portraits in memorial books. But some sons have left no trace of a face and remain invisibly lost as men.

Almost a century later, why do we write so many books about the Great War? And why do they invariably focus on those who died? Gertrude Stein's oft-quoted ‘lost generation' referred not to the dead of the war, but to its war-interrupted survivors, damaged and drifting in the 1920s. Many indeed died but three-quarters of Rosslyn Park's estimated 350 members who fought came through alive, although not always untouched in body or mind. There are as many heroic stories to be told of players who survived. In his 1918 VC citation, Captain Reginald Hayward:

‘ ...displayed almost superhuman powers of endurance. In spite of the fact that he was buried, wounded in the head and rendered deaf on the first day of operations and had his arm shattered two days later, he refused to leave his men, even though he received a third serious injury to his head, until he collapsed from sheer exhaustion.' (4)

In hearty disregard for mortality, the superhuman Hayward lived until 1978. Yet it is Arthur Harrison VC, who dies sixty years earlier in a storm of bullets at Zeebrugge, who fascinates and whose equally vivid story is told here.

10) Arthur Leyland Harrison VC, hero at Zeebrugge

A fortunate few achieved some small measure of youthful fame before the whistle, but rarely did it last, overwhelmed by the wave that washed away their Edwardian world. None lived to write the memoirs and autobiographies which flooded onto the market in the 1920s and by which we know of the survivors' experiences. None were interviewed as forgotten voices in their declining years by historians rushing to preserve their accounts before the virus of death deleted them. The only true death is to be forgotten and the book which resulted from the research hopes to resurrect their ghosts and remember them as men. A project that was born out of curiosity, took shape through a website and gave rise to a junior rugby tour to the Somme battlefields and the Armistice town of Compiegne, has now become a living memorial online and now in print.

The book tells of fifteen lives cut short, and touches on many others. Few of these mostly young men had time to marry and father children who would live after them and tend the flame of memory. If they wrote letters home, as surely they all did, only a few have been spared by time; these glimpses into the thoughts of Alec Todd, Jack Bodenham, Jimmy Dingle, or Guy du Maurier are precious. Many did not even leave mortal remains: thirty-four bodies - two entire teams and more - were never found and have no known resting place. It is the author's hope that more details of these men will emerge from knowledgeable WFA members, that they be not forgotten. Contact is welcomed through info@rugbyremembers.co.uk

The Final Whistle: the Great War in Fifteen Players by Stephen Cooper is published by The History Press

Article and images copyright WFA/Stephen Cooper 2012

This is the featured article - kindly contributed by Stephen Cooper - from Stand To! No 95, published September 2012. Stand To! is the journal of The Western Front Association.

References

(1) Rex Alston, One Hundred Years of Rugby Football at Rosslyn Park 1879-1979, Club archive.

(2) Letter to Howard Sturgis, Letters of Henry James Vol 2 ed Percy Lubbock, Scribner, New York 1920.

(3) The Times, 3 November 1915.

(4) London Gazette, 24 April 1918.

Further Reading:

The Easter Rising - Dublin 1916

The Battle for Mount Street Bridge

The Battle for the South Dublin Union

The golden locket, the hidden grave and the forgotten soldier