The R38 disaster 24 August 1921

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The R38 disaster 24 August 1921

At the start of the war, in contrast to Germany, the British had limited experience of airships.

Under the Royal Naval Air Service there were only a handful of airships in service but with increasing U-Boat activity and the resultant impact on shipping, the Navy began to further develop its use of airships to counter the U-Boat threat.

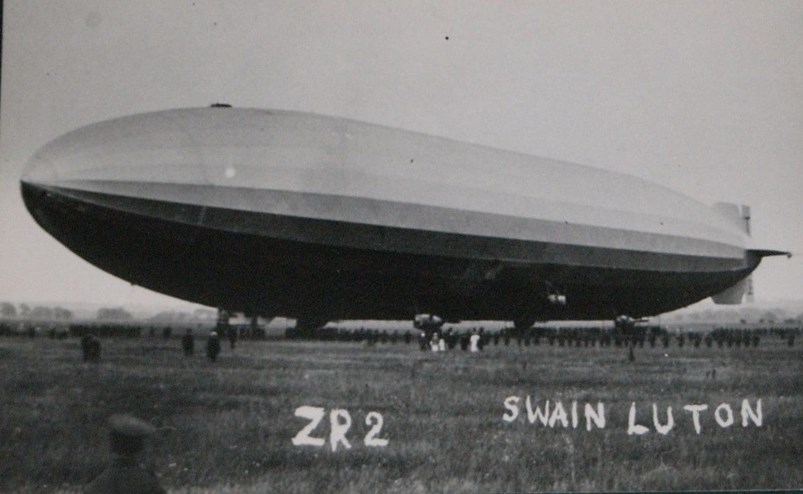

The R.38 class (also known as the A class) of rigid airships was designed for Britain’s Royal Navy during the final months of the war, intended for long-range patrol duties over the North Sea. Originally, the order was for four, but three were later cancelled after the Armistice. The one completed airship – R.38 – was sold to the United States in October 1919 before its completion. The Americans named the airship ZR-2. At the time, it was the largest airship to be constructed.

Above:R.38. Photo -britishairshippeople.org.uk

It began trial flights in June and July 1921 from the Howden Airbase, situated near the town of Howden and south east of York. A number of American servicemen – known as the Howden Detachment – came over to Britain to gain experience of flying R.38 before it would be flown back the United States.

Above: The Howden Detachment. Photo: HistoricalHowden.com

The first three trial flights in June and July 1921 revealed a number of faults which were rectified. But on the fourth of its trial flights on 24 August 1921, R.38 was destroyed when it broke up in flight and then was ripped apart by explosions. There were 49 on board – only 5 survived.

A report in the Belfast Telegraph described that:

“A wireless message was received at Howden Aerodrome two minutes before the great airship fell in flames and smoke, but it gave no hint of the tragedy which so quickly followed. ‘Running in fine condition’ the message ran and in two minutes the vessel crumpled and fell to the noise of explosions and the glare of flames.”

“Thousands were watching the beautiful sight as the vessel, with her silver coat glistening in the sun, sailed majestically overhead, about 1,000 feet up. She disappeared in the clouds and on emerging it was apparent to the most uninitiated that something untoward had occurred. The airship was crumpling as though breaking into two portions. Disabled as she was, the R.38 was headed towards a wide portion of the river, and she laboured heavily ahead. A huge portion became detached and fell, being followed in the space of a few seconds by what is believed to be one of the engines and a gondola. There followed a series of explosions, two of them of a very pronounced character, the noise of which could be heard for many miles. Fire then broke out on the ill-fated craft, which became enveloped in dense volumes of black smoke, and the mangled remnants gradually fell until they alighted on a sandbank in the Humber which was at low water”.

“...it was an awesome spectacle, and its terrible effects have plunged two nations into mourning, for on board, in addition to the personnel of the British crew, were a number of Americans, some of them high-placed officials…”

Above: A picture of the wreckage from the stern of the airship as it appeared on the front page of The Sheffield Independent 26 August 1921 (from the British Newspaper Archive).

In the days following the tragedy, newspapers would report that bodies were being found along the Humber.

A memorial service was held in Hull, with a public funeral for many of the victims.

Above: The funeral procession. Photo – HistoricalHowden.com

In September 1921, a Memorial Service was held in Westminster Abbey.

Of the British crew, 28 were killed, with 14 Americans killed. A number of those killed are buried in Hull Western Cemetery.

Above: Hull Western Cemetery

Air Commodore Edward Maitland was the highest ranking British officer to perish in the tragedy. He had taken up ballooning whilst in the army in 1907 and for a short time commanded the air battalion section of the Royal Engineers from 1911 to 1912. On the formation of the RFC, he was given command of 1 Squadron (airships) until his transfer to the Royal Naval Air Service in 1913. In 1919, now Acting Brigadier-General in the RAF, he made the flight across the Atlantic and back in the airship R.34 – a feat which had attracted the American’s interest and subsequent purchase of R.38.

Above: Air Commodore Edward Maitland CWG, DSO, AFC. Photo – rafweb.org

Flight Lieutenant Godfrey Main Thomas DFC from Jamaica had lost three brothers in the war.

Above: Flight Lieutenant G.M. Thomas DFC

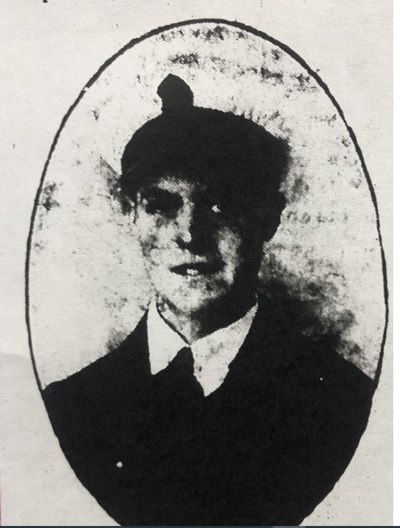

Aircraftsman Charles William Penson from Sleaford, was also killed in the disaster. The eldest of seven children, he had joined the Navy in 1916.

Above: Aircraftsman 1st Class Charles William Penson. Photo – lincolnshireworld.com

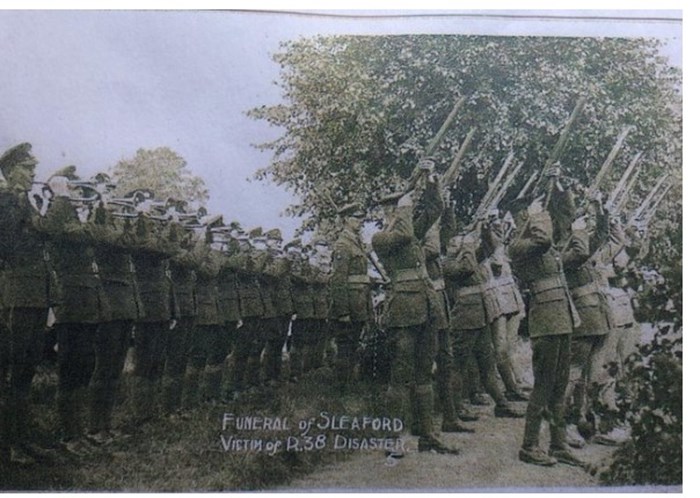

Above: Charles Penson’s funeral at Sleaford and his gravestone in Sleaford Cemetery. Photos – lincolnshireworld.com

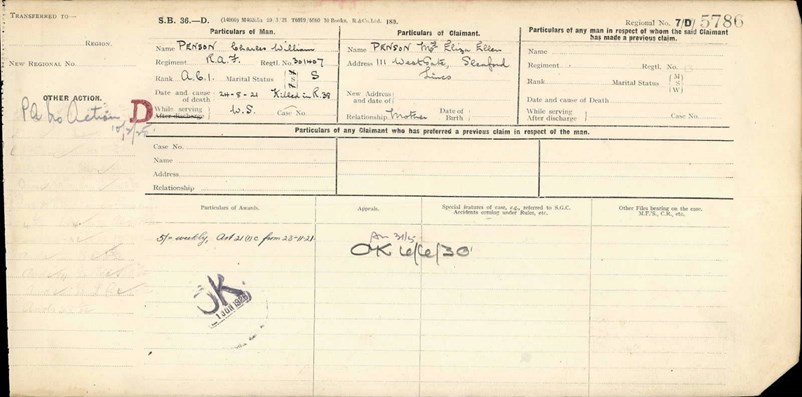

Above: Pension Ledger for Charles William Penson.

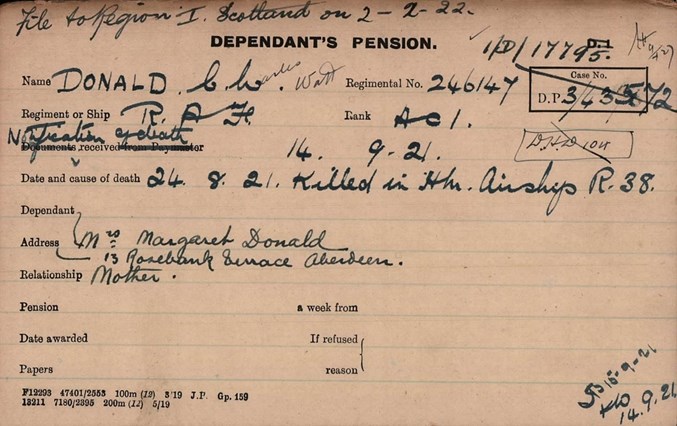

One of the youngest casualties, aged 20, was AC1 Charles Watt Donald from Aberdeen who had joined the RAF in 1918. He is buried in Aberdeen’s Nellfield Cemetery

Above: The pension card for Charles Watt Donald

A Memorial to those lost on the R.38 was erected in the grounds of Hull Cemetery.

Above: The R.38 Memorial. Photo – CWGC

Following the loss of the airship, an inquiry was held, with the outcome reported in the press in October 1921. This found that the R.38 had broken into two parts due to a failure in the structure in the rear of the after-engine cars when being subjected to tests. The fire that broke out after this was deemed to have been the major cause of loss of life. Some criticism was made regarding the extent to which the design of R.38 had been subjected to examination prior to construction. Its loss effectively ended Britain’s military interest in airships.

Article by Jill Stewart

Hon. Secretary, The Western Front Association