Was Lord Kitchener Gay?

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Was Lord Kitchener Gay?

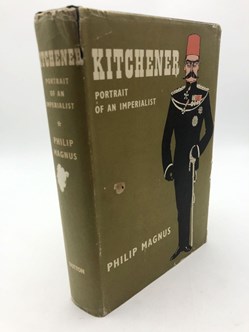

Ever since the publication of the biography entitled ‘Kitchener: Portrait of an Imperialist’ by Philip Magnus in 1958 there have been repeated rumours about Lord Kitchener’s sexuality.[1] The article below by Jeremy Paxman was first published on his website (https://jeremypaxman.co.uk/revelations/was-kitchener-gay) in 2014. Footnotes and photos have been added to the original plus passages from the Philip Magnus biography to supplement and provide further context to Paxman’s piece.

On a sunny day, Marwick Head is a glorious place to be. Sandstone cliffs tumble sheer into peacock and petrol-blue water. And at the top of the headland stands a squat, crenellated tower.

Above: Marwick Head

Above: A new memorial wall was constructed recently at the base of the memorial.

Above: Part of the new memorial includes a panel which lists the fourteen strong party, led by Kitchener who were all drowned on 5 June 1916.

Visible for miles, it has no obvious function — too fat to be a lighthouse, too small to be a castle. A stone panel explains: ‘This tower was raised by the people of Orkney in memory of Field Marshal Earl Kitchener of Khartoum on that corner of his country which he had served so faithfully nearest to the place where he died on duty. He and his staff perished along with the officers and nearly all the men of HMS Hampshire on June 5, 1916.’

Above: HMS Hampshire

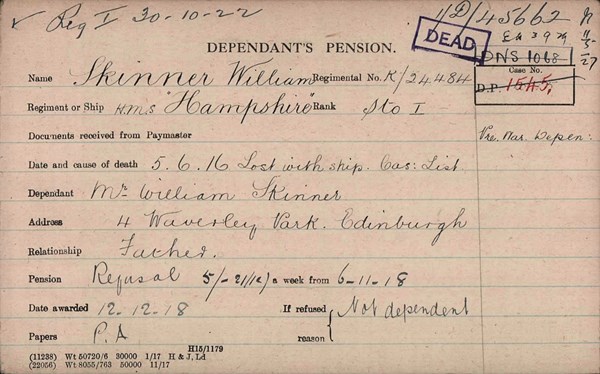

Though hardly remembered today, the wreck of the Hampshire was seen at the time as little short of a national disaster. Hundreds of men perished, among them the best-known soldier in the English-speaking world, who became the most senior officer from either side in the First World War to die in active service.

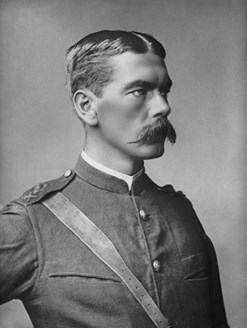

Above: Kitchener

When news of the loss of HMS Hampshire reached London, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle reached for his ink pot. Lord Kitchener, he said, had left behind ‘the memory of something vast and elemental, coming suddenly and going strangely, a mighty spirit leaving great traces of its earthly passage’.

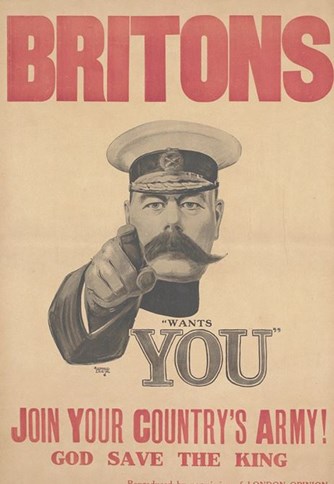

When those shots rang out in Sarajevo in 1914, Britain had been without a war secretary. Kitchener, 64, was a soldier rather than a politician, yet the obvious choice for the job. At 6ft 2in, with piercing blue eyes set in a weathered face, he was an imposing presence. ‘If not a great man, he was, at least, a great poster,’ the prime minister’s wife, Margot Asquith, was supposed to have sneered, referring to the famous recruiting advertisement.

Above: Margot Asquith

Above: That Poster

But without his appeal for volunteers Britain could not have survived the early stages of the fighting. He soon became to the First World War what Churchill would later be to the second.

This vain, imposing, arrogant man arrived at the War Office garlanded with medals, stars and satin sashes for raising the Union Jack over numerous corners of foreign fields.

Having survived a brutal upbringing in Ireland (his father disdained blankets, preferring to sleep under sheets of newspaper sewn together, and once punished his son by staking him out on the lawn, wrists and ankles tied to croquet hoops), he had risen to become the greatest public expression of ramrod uprightness.

Kitchener had already served as consul-general in Egypt and commanded the army in India. Most famously, he was ‘the Sudan machine’ — the man who had crushed the massive force of Islamists which had risen in the desert against the British Empire.

Above: Charge of the 21th Lancers at Omdurman. Oil on canvas

Even though he had said several times that he would rather sweep the streets than have a job in the War Office, when conflict broke out, Kitchener was immediately appointed Secretary of State for War.

The Cabinet table was an odd place for a man who despised politicians. And, by 1916, many of them were coming to despise him, too.

Thousands of British lives had been lost in the doomed Gallipoli adventure, and Kitchener carried the can for a calamitous cock-up in the supply of artillery shells in the spring of 1915. Two years into the war, Prime Minister Herbert Asquith felt able to reduce Kitchener’s responsibilities but dared not cast him completely aside.

But then came an opportunity to get the man out of the way, for a little while at least.

The Orkney Islands, specifically Scapa Flow, was Kitchener’s destination when, on June 4, 1916, he boarded a night train at King’s Cross station for the 700-mile journey north. The following morning he crossed to the Scapa anchorage. Here he boarded the armoured cruiser HMS Hampshire to embark upon a secret voyage to Archangel in northern Russia, for talks with Britain’s Russian allies.

The tsar was begging for fresh supplies of guns and explosives, and Britain was worried whether Russia, which had taken enormous casualties, would have the will to stay the course of the war. Kitchener jumped at the idea of leading a mission of reassurance. As the commander of the Grand Fleet, Admiral John Jellicoe, recalled later, the war secretary ‘expressed delight at getting away for a time from the responsibilities and cares attaching to his Office’.

The captain of the ship carrying the war secretary and his dozen-strong staff had been ordered not to follow the obvious route to Russia.[2] Instead of using the sea lanes regularly patrolled by mine-sweeping vessels, the Hampshire was to hug the western coast of the Orkneys and only head for Russia once it had passed to the north of the islands.

Above: Kitchener boards HMS Iron Duke from HMS Oak at 12.25pm on 5 June 1916 prior to lunching with Admiral Lord Jellicoe at Scapa Flow.

Above: Admiral Jellicoe bidding farewell to Field-Marshal Kitchener before his embarkation aboard the H.M.S. Hampshire. Kitchener is the third figure from right. Admiral Jellicoe is seen standing beside Kitchener, shaking hands with Hugh James O'Beirne of the Foreign Office, who also perished in the sinking.

There was certainly a reasonable argument for the unusual course, for a fierce storm was blowing from the north-east and the lee of the islands offered some shelter. Even though the sea was far too rough to launch a torpedo, the Hampshire was instructed to maintain a speed of 18 knots to outrun any U-boats.

That afternoon the storm changed direction and was soon blowing into the face of the warships. Nonetheless, Herbert Savill, the captain of the Hampshire, had soon outpaced the two destroyers assigned as escort vessels. By 7pm he had sent them back to base.

Above: Taken aboard HMS Iron Duke in Scapa Flow on afternoon of 5th June 1916. Col Fitzgerald (Kitchener's Military Secretary) is just stepping out of the doorway to the left of the photo. He died that night. The others are Lord Jellicoe (at the foot of the ladder) and Admiral Sir Frederick Dreyer (Captain of Iron Duke) with Lord Kitchener

Less than an hour later there was a tremendous explosion. The Hampshire shuddered and took on water.

‘It was as though an express train crashed into us,’ recalled a stoker who survived.

Within minutes, the vessel was sinking by the bows, with most of the lifeboats unlaunchable in the storm. It was still daylight, and in the Orkneys, observers from the Royal Garrison Artillery had seen the Hampshire explode a mile or so off the coast.

The postmistress in the remote settlement of Birsay sent an SOS by telegraph to alert the naval authorities. But the Hampshire went down in 15 minutes — time only to launch three small life rafts, which were soon hopelessly overcrowded.

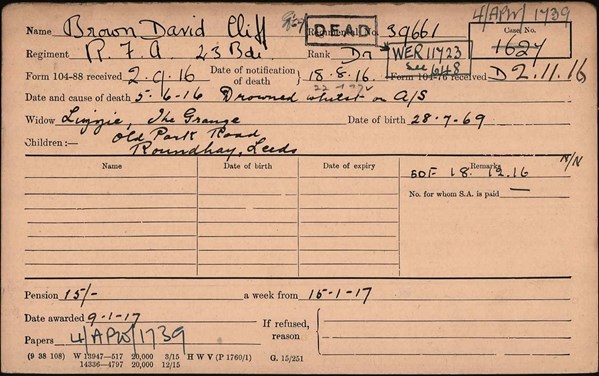

Above: Driver David Brown was part of the 14 man contingent in Kitchener’s party. He was a servant to Brig-Gen Ellershaw.

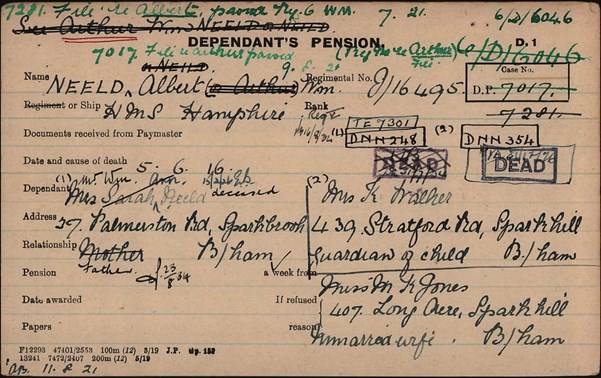

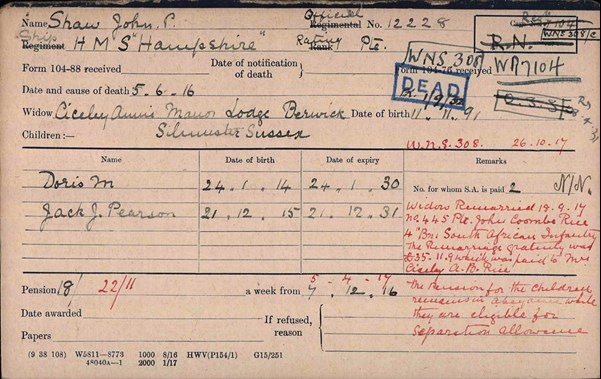

Above: Three pension cards of men who were drowned on HMS Hampshire. The final death toll was 737.

Of Lord Kitchener, there was no sign at all. Though corpses continued to wash up for weeks afterwards, Kitchener’s body was never found.[3]

Two survivors later testified to an Admiralty inquiry that as the ship sank, the British war secretary emerged from the gun room, when there was a call of ‘Make way for Lord Kitchener!’. He was last seen standing in his uniform on the starboard side of the quarterdeck, calmly talking to two staff officers as the ship went down.

The King noted his personal distress at the news of Kitchener’s death in his diary: ‘It is indeed a heavy blow to me and a great loss to the Nation & the Allies.’ He ordered Army officers to wear black armbands for a week. Across the nation, hands trembled as people read of the calamity. The Daily Mirror distributed 1.5 million copies that day.

Above: The Daily Mirror headline

The conspiracy theories began almost at once. How could such an important figure, in the full protection of the greatest navy in the world, be dead?

On June 7, the Evening News reported that all over London people believed the sinking had been the work of German secret agents. Others even claimed that the disaster had been perpetrated by the British government.

The Admiralty conducted two investigations, the first in the immediate aftermath of the disaster, the second ten years later. Each concluded that the ship must have hit a mine.

In July, Sir George Arthur, Kitchener’s secretary, wrote to tell Admiral Jellicoe that the supposedly secret visit to Russia had been common knowledge there long before he had even arrived in Scapa Flow.

Above: Admiral Jellicoe

Had German intelligence intercepted British signals, thereby leading to the mining of the waters off Marwick Head? Should Admiral Jellicoe have insisted that the Hampshire take the unusual course? Why had his staff ignored not one but three intelligence reports of German U-boat activity in the area?

An Admiralty directive after the disaster ordered that if Lord Kitchener’s corpse was to be found ashore, it should be retrieved in secret and put inside a special ‘metal-lined shell’ carried on board a Royal Navy ship. Why? The conspiracy theories refused to die.

Another concerned MP, Edwin Scrymgeour, said that he knew a secret police report was being kept hidden, proving that the Admiralty had botched the rescue operation.

Oscar Wilde’s former lover, the Poet Lord Alfred Douglas, claimed a conspiracy which took in Winston Churchill and a worldwide network of Jews. It was also said that the Hampshire had been carrying vast quantities of Gold to be given to the Russians.

It was only in the late 1960s that the records of Admiralty investigations — coming to the pedestrian conclusion that the ship had almost certainly struck a mine — were declassified.

Reports from captured German archives note that the log of submarine U75 recorded her scattering mines in the area just before the disaster — the U75 claimed the Hampshire as one of her victims.

Yet when the Kitchener files in the National Archives were reviewed by officials in 1973 and 1981, two were still judged unsuitable for publication and sealed until the end of 2015 and the end of 2025. If there was a conspiracy, it was being hidden from sight for a remarkably long time.

Was there really a cover-up? Or is there something in the death of a hero that makes a conspiracy seem more believable?

Orkney’s folk-memory seems to hold it as fact that local people desperate to rescue sailors had been blocked from doing so, sometimes at the point of a bayonet. There are still Orcadians who believe British military headquarters ordered the local lifeboat not to attempt a rescue. Much of this is nonsense. Yet the bad smell lingers.

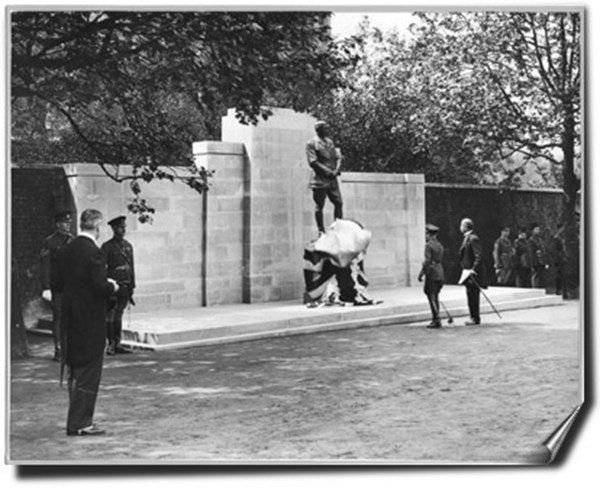

Though several notables attended the unveiling of Kitchener’s statue on Horse Guards Parade, not a single senior member of the government came to the dedication of the Orkney memorial.[4]

Above and below: The Kitchener Memorial at Horse Guards Parade.

Above: The Kitchener Memorial at Marwick Head, being unveiled by Lord Horne.

Below: Seen from above the memorial overlooks the area off Orkney where HMS Hampshire was sunk

Admiralty investigations into the sinking concluded there was no conspiracy. They would, wouldn’t they? And what could be so sensitive that two files in the National Archives remained closed to the public until the end of 2015 and 2025? Was it something about his private life?

Kitchener was long ago conscripted into the ranks of homosexual history.

He was accompanied on his final journey by the ever-present, ‘Fitz’ — Captain Oswald Fitzgerald, of the 18th Bengal Lancers — the latest in a series of handsome younger men on his staff.[5]

Fitzgerald had saved his boss from a would-be assassin in Cairo and Kitchener had planned to bequeath his 5,000-acre African estate to him.

Above Lord Kitchener and his personal staff in India. Fitzgerald stands 3rd from left, without a hat. Kitchener is on the extreme right of the group.

As it was, ‘they died in each other’s arms when the HMS Hampshire struck a mine off Orkney in 1916’, the gay activist Peter Tatchell informed Guardian readers ten years ago. There is not a shred of evidence to support this claim.

It is true that Kitchener never married. It is certain that Fitzgerald also died when the Hampshire went down,[6] and that he had been with Kitchener for nine years, though that hardly adds up to conclusive evidence.

The closest he came to marriage was in 1883 / 1884 when Kitchener was in Egypt. Kitchener was aged 33 and an engagement to Hermione Baker was very much on the cards. Hermione was aged 16, so it is possible that an engagement may have had to wait until her 18th birthday. Tragically Hermione died of Typhoid fever in Cairo in January 1885.[7]

Above: Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener by Alexander Bassano half-plate glass negative, 1885 Purchased, 1996 Photographs Collection NPG x96297 (C) National Portrait Gallery

The origins of the rumours about Kitchener’s sexuality if not started by, were at least compounded by the biographer Philip Magnus who in his 1958 book made a number of statements hinting at Kitchener’s homosexuality.

Magnus writes

“To replace Maxwell [his previous ADC who had been ‘the reigning favourite for six years’]…. Kitchener appointed Capt OAG Fitzgerald….at the end of July1907 Fitzgerald went home to England on leave and while he was away Kitchener was intensely lonely for some weeks. And after his return, Fitzgerald established himself so securely in the affections of his chief that Kitchener never looked elsewhere and their intimate association was happy and fortunate. Fitzgerald, like Kitchener was a bachelor and a natural celibate; he devoted the whole of the rest of his life exclusively to Kitchener and except for a brief period early in 1910 he never quitted Kitchener’s side until they met their death together on the fatal voyage to Russia in June 1916”

Magnus also states that Kitchener left a substantial part of his estate to Fitzgerald. Describing Broome Park (Kitchener’s residence) Magnus tells us

“…he (Kitchener) had personally designed the special fountain embellished with nymphs and sea monsters [and] had arranged for four pairs of boys [statues]… to stand at the four corners of the square; and in the modeling of those bronze figures Kitchener had taken a boyish delight. The first pair were running; the second wrestling; the third embracing and the fourth dancing.”[8]

Above and below: Broome Park today

At the time of Kitchener’s eminence (and indeed until 1994), homosexual activity in the army was a court martial offence. But homosexuals were, and are, almost certainly as well represented in the army as in any other walk of life.

The occasional remark from enemies about his near-kleptomaniac enthusiasm for fine porcelain or his passion for orchids, textiles, flower arranging and his pet poodle proves nothing. Whatever his aesthetic enthusiasms, there is not a jot of proof that Kitchener was what we would understand to be an active homosexual.[9][10]

So what could be sufficiently sensitive about this great British hero, and his death, that one government after another deemed the files about him should stay secret so long?

I submitted a Freedom of Information Act request to have the Kitchener files declassified, and discovered that, alas, our heroes succumb to the same plodding fate as the rest of us.

The files are as dull as ditch water. The Inland Revenue wants to get its hands on the proceeds of a sale of a few bits of pottery from the Kitchener estate. There is an undignified wrangle over whether Captain Fitzgerald might have lived a little longer than Kitchener, and therefore could be liable for taxation on the African estates he inherited as he struggled for life in the icy waters off Orkney. There are pages and pages of turgid legalese. But there are no revelations about Kitchener’s private life, no mutters of official anxiety, nothing to suggest a conspiracy of any kind.[11]

The banal is always more likely than the bizarre. With all its strange public displays of grief and crackpot conspiracy theories, the reaction to Kitchener’s disappearance had about it some of the characteristics of the death of Princess Diana.

Kitchener was a hero for a different age: who can even name a single serving general today? But once someone has found a place in the popular imagination, we do not let them go easily.

Jeremy Paxman

The Lord K and The Western Front Association

Major Henry Herbert Kitchener, 3rd Earl Kitchener (24 February 1919 – 16 December 2011) was a Vice President of The Western Front Association. He was the son of Captain Henry Franklin Chevallier Kitchener, Viscount Broome, only son of Henry Kitchener, 2nd Earl Kitchener. The 2nd Earl was the nephew of the Field Marshal (Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener).

The 3rd Earl Kitchener was the last of the ‘original' Vice Presidents of The Western Front Association and his passing in 2011 marked the last of those invited to this role by the WFA's founder John Giles.

Further reading

‘Kitchener of Khartoum’ and HMS Hampshire

Footnotes

[1] Herbert Horatio Kitchener was a controversial figure even in his own day, "hated or traduced by some, almost worshipped by others" but his modern reputation really dates from the publication in 1958 of Philip Magnus's Kitchener: Portrait of an lmperialist. From this work comes the popularly accepted theory of Kitchener's homosexuality, for which there is no contemporary evidence whatever, as well as, worse, the denigration of his victories at Omdurman and over the Boers.

This is the conclusion of the Kitchener's Scholar's Association (www.kitchenerscholars.org/kitchener-of-khartoum)

[2] The mission to Russia comprised the following group:

BROWN David Cliffe Driver, RHA. 39661 (engaged as a servant to Brig Gen Ellershaw)

DONALDSON Hay Frederick T/Brig-Gen (Chief Technical Adviser to the Ministry of Munitions)

ELLERSHAW Wilfrid, T/Brig.-Gen. (Aide-de-Camp to Lord Kitchener)

FITZGERALD Oswald Arthur Gerald Brvt. Lt.-Col. (Personal Military Secretary to Lord Kitchener)

GURNEY James Walter (Valet to Hugh O'Beirne)

KITCHENER Horatio Herbert, Field Marshal (Secretary of State for War)

MCLOUGHLIN Matthew. Det. Sgt. (Kitchener’s Scotland Yard Protection Officer)

MACPHERSON Robert David 2nd Lt. (Interpreter - he was born in Petrograd and aged 19. He is buried at Lyness Royal Naval Cemetery)

O'BEIRNE Hugh James (Foreign Office Minister). Hugh O’Beirne missed the train carrying Kitchener’s party north but he managed to catch a special service which meant he still arrived in time to make the fateful trip.) . His first posting was in St. Petersburg, where he learnt to speak Russian, and after service at Washington, Constantinople and Paris he returned to the Embassy as Counsellor in July 1906. He remained in Russia for the next nine years and played a valuable role in the development of UK-Russian relations, symbolised by the signing of the Anglo-Russian entente of 1907. He was promoted to the rank of Minister in August 1913.

RIX Leonard Charles Clerk (Shorthand Clerk to Mr. O'Beirne)

ROBERTSON Leslie Stephen Lt.-Col. (Deputy Director of Production at the Ministry of Munitions and the Secretary of the Engineering Standards Committee)

SHIELDS William (Valet to Lt Col Fitzgerald) (formerly 10113 East Lancs)

SURGUY Henry (Valet to Lord Kitchener)

WEST Francis Peter (Valet to Brig Gen Donaldson)

[3] There were just 12 survivors out of the 749 on board. Kitchener, being a serving soldier is commemorated by the CWGC on the Hollybrook Memorial, Southampton along with four others on the mission. Most of the sailors are commemorated on the Portsmouth Naval Memorial, with others on the Chatham and Plymouth Naval Memorials. Over 120 bodies were recovered. Most of these are buried at Lyness Royal Naval Cemetery

[4] Paxman is probably making too much of this.

The Memorial on Horse Guards was erected by parliament (It contains the following inscription: KITCHENER/ 1850–1916/ ERECTED BY PARLIAMENT) and was unveiled by H.R.H. the Prince of Wales on 9 June 1926. It backs onto the rear wall of the garden at 10 Downing Street. Approaching it is likely to draw a response from the armed police who are always on duty!

The Orkney Memorial is not a parliamentary memorial. An inscription reads 'This tower was raised by the people of Orkney in memory of Field Marshal Earl Kitchener of Khartoum on that corner of his country, which he had served so faithfully, nearest to the place where he died on duty'. It was unveiled on 2 July 1926 by Lord Horne (General Horne, commander of the First Army). Footage of the unveiling can be seen here > VIDEO

[5] Paxman says Fitzgerald was his Aide-de-Camp. This would appear not to be the case, Brig Gen Wilfird Ellershaw seems to have been the ADC with Fitzgerald being Kitchener’s Personal Military Secretary.

[6] Fitzgerald is buried at Eastbourne (Ocklynge) Cemetery

[7] Hermione’s family had previously been in the public eye for all the wrong reasons. Her father was Lt-Colonel Valentine Baker , an army officer who was dismissed after a court case in 1875 which saw him found guilty of indecent assault in a railway carriage on the South Western railway line. After his release from prison he served in the Ottoman Army as Lieutenant General At the age of 55, in 1882, he was given command of the Egyptian police. Clearly at that time his daughter met, and fell in love with Kitchener. More information about the scandal can be found here > Article

[8] Kitchener: Portrait of an Imperialist. Philip Magnus. 1958. Magnus also makes other implications by writing (when receiving guests) “[Kitchener] arranged the flowers with his own hand, and took immense pains to ensure that no glass or vase, and no knife form or spoon was a fraction of inch out of position”.

[9] A biographer of Kitchener John Pollock declares him not to have been homosexual and also rejects the (more probable) explanation that he had homosexual inclinations but chose to be celibate. (Kitchener by John Pollock, 598pp, Constable, £20)

[10] We also have C Brad Faught in Kitchener Hero and Antihero (IB Taurus & Co Ltd, 2016) saying this: “…Kitchener was emotionally repressed – just like many others of his time – but made even more so by the early death of his mother….he seems to have been ‘morbidly afraid of showing any feeling’….Is that evidence of suppressed homosexuality? Probably not.” And Faught also observes “…unlike his (in)famous contemporary Oscar Wilde, there simply was no action. Nor were there words. Neither his nor really anyone elses’s. Ultimately, we are left with an issue about which historians can say almost nothing useful."

[11] What do the long- suppressed documents show? According to another author, David Laws, ‘miscommunication, muddle and delay’. In high places incompetence was evident too. The Hampshire’s route was chosen by the commander in chief of the fleet, Admiral Jellicoe. Laws says ‘ Admiral Jellicoe sent one of the most important members of the British government on a sea voyage on a route chosen on the basis of outdated weather assumptions, through waters unswept for mines, on the basis of groundless hunches about the low risk of mine presence.’ Perhaps this is why the files were classified for so long? (Who Killed Kitchener? The Life and Death of Britain’s Most Famous War Minister by David Laws, Biteback Publishing, £20)