Death From the Skies: Doullens Citadel, 30 May 1918

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Death From the Skies: Doullens Citadel, 30 May 1918

Female nurses performed a vital part in caring for the sick and wounded of the Great War. They did not, however, normally serve further forward than the Casualty Clearing Stations (CCS) that were usually positioned several miles behind the front lines safe from all but the longest range shelling.

Amongst the nurses were contingents from the Empire, with Canada providing many for Canadian run CCS and hospitals. According to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) a total of 44 Canadian nurses and matrons of the Canadian Army Medical Corps (CAMC) or Canadian Army Nursing Service (CANS) died during the Great War. The event that killed the largest number of Canadian nurses was the torpedoing of the hospital ship Llandovery Castle about 110 miles south-west of the Fastnet Rock on 27 June 1918, in which 14 perished.

The majority of the others died in Canada or the UK from illness, but 10 are listed as being buried in France (none in Belgium). There are two buried in Terlincthun British Cemetery; four in Etaples Military Cemetery and one in Wimereux Communal Cemetery. The remaining three are buried in Bagneux British Cemetery, about 2 km south-west of where they died in the Doullens Citadel, home to the 3rd Canadian Stationary Hospital (CSH).

Whilst the nurses were normally kept out of artillery range, as the war developed the Germans mounted air raids on the Allied rear areas and by 1918 this had become a common feature on nights suitable for flying. There were several instances of hospitals being targeted; whether by accident or design is difficult to establish. A bombing raid on Doullens in the early hours of 30 May 1918 was to cause the greatest loss of Canadian nurses in a single incident on the Western Front.

The 3rd CSH had been established in buildings within the walls of the Citadel at Doullens since April 1916.It catered for a wide-range of injuries, specialising in ‘surgical head cases and special nervous cases such as shell shock, neurasthenia and dementia’. The hospital took in patients from a number of CCS for treatment before returning them back to duty, or passing them onto other establishments for further treatment. The hospital often accommodated more than600 patients and an indication of how busy it was comes from the 3rd CSH War Diary, which shows that it admitted 229 and discharged 376 patients on 28 May 1918; with another 176 admitted and 192 discharged on the following day. Some of those ‘discharged’ unfortunately died while in the care of the 3rd CSH and were buried in nearby cemeteries.

The evening of 29 May 1918 does not seem to have been exceptional and, as well as the patients receiving care on the wards, three surgical teams were performing operations. At about midnight two of the teams, having completed their operations, left the Operating Room for a meal. At 12:25 a.m. on the 30th a German aircraft flew overhead, dropped a flare and then a bomb that:

Struck the main building over the sergeants quarters, Ward S.6 (officers ward) operating theatre and X-Ray room which collapsed immediately. Almost instantly a fire broke out and the whole group of buildings in the upper area were threatened. The alarm was given at once and every effort made to save the patients and combat the fire. The Nursing Sisters and orderlies worked splendidly and with the assistance of other members of the unit rapidly removed all patients to places of safety. There were no other casualties other than those killed by the bombs.

The War Diary points out at some length the fact that the hospital should have been visible from the air but, even as it was in flames and the buildings fully illuminated, ‘the aeroplane returned and dropped more bombs, fortunately without doing any damage’.

All the sergeants in their room became casualties, and all the officers on Ward S.6 were killed, although, as it was not fully occupied, the toll was not as large as it might otherwise have been, however, Nursing Sister Dorothy Baldwinwas amongst the dead. In the Operating Room two surgeons, their patient, and all the theatre staff, including Nursing Sisters Eden Pringle and Agnes Macpherson were killed. The surgeons were Captain Ethelbert Meek, CAMC, and Lieutenant Abner Sage of the American Medical Reserve Corps.

The victims were buried in Bagneux British Cemetery on 31 May, with Bishop Fallon of London, Ontario, who was visiting the Western Front, officiating. As is not unusual, the actual number of casualties involved is difficult to reconcile. The War Diary states that a total of 32 were killed, however, only 25 are buried in Plot III, Row A, where the CWGC indicates victims of the bombing are buried. The CWGC does list a total of 37 buried in Bagneux with a date of death of 30 May but, as 12 are buried in Plot II or named on special memorials, it is unclear whether any of them are connected with the bombing. The American surgeon, Abner Sage, was initially buried in Bagneux, but was later exhumed and reinterred with his countrymen in Bony American Cemetery (Plot A, Row 33, Grave 6) about 70 km away.

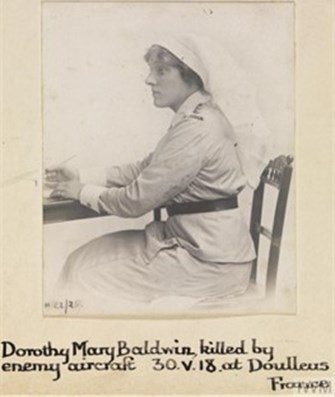

Of the victims, Nursing Sister Dorothy Baldwin was born in Toronto in October 1891. A fully qualified nurse she enlisted in early May 1917, and arrived in Britain on 8 June. She briefly served at the Ontario Military Hospital, Orpington, Kent, before transferring to France and the 3rd CSH in late July 1917.

Above: Nursing Sister Dorothy Baldwin. IWM WWC H22-25

Above: Dorothy Baldwin’s grave. Photo - Derek Bird.

Nursing Sister Agnes Macpherson was born in Brandon, Manitoba, in March 1891. She enlisted as a qualified nurse in November 1916 and arrived in London on the last day of the year, before working at Moore Barracks Hospital, Shorncliffe, Kent. Nine months later she was transferred to the 3rd CSH in France. She was awarded the Royal Red Cross for her services to nursing.

Above: Nursing Sister Agnes Macpherson’s headstone (photo by Derek Bird) and image from IWM Lives of the First World War.

Nursing Sister Eden Pringle was born in Glasgow, Scotland, in September 1893. She emigrated to MacGregor, Manitoba, with her mother and siblings in 1906, to join her father who had already been farming in Canada for three years. At the age of 18 she was working as a teacher, but later went to Vancouver to study nursing at the city’s General Hospital. She graduated in 1915 and worked in the Operation Room until her enlistment in early May 1917. She sailed to Britain at the end of that month and was in initially posted to the Canadian Red Cross Hospital, Buxton, Derbyshire, that was situated in the former Peak Hotel (now Buxton Museum and Art Gallery). Eden Pringle was then sent to the 3rd CSH in late July 1917, where she remained until her death in the Operating Room the following May. Post-war she was honoured at Vancouver General Hospital when a ward was named after her. Also, the Eden Lyal Pringle Chapter of the women’s charitable organisation, Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire, was founded in her memory.

Above: Nursing Sister Eden Pringle IWM WWC H22-27

Above: Eden Pringle’s headstone with inscription ‘Faithful unto Death’. Photo - Derek Bird.

The Canadian surgeon, Captain Ethelbert Meek, who died while operating on a patient, was born in Truro, Nova Scotia, in November 1877 and resided in Regina, Saskatchewan. He enlisted in January 1916 and proceeded to Britain on the RMS Olympic in late April 1917. He was first appointed as Medical Officer to the 32nd Reserve Battalion, and then to the Duchess of Connaught’s Canadian Red Cross Hospital at the Cliveden Estate, Taplow, Buckinghamshire. In February 1917 he was sent to France and served at various times with both the 2nd and 3rd CSH, and was also attached to the 2nd Canadian CCS in July 1917 for three months, after which he was admitted to the 14th General Hospital, Boulogne, suffering from boils. After a week’s treatment he was posted back to the 2nd CSH, before being transferred to the 3rd CSH just over a month before being killed. The inscription on his headstone reads: ‘A gifted surgeon killed at the post of duty. Beloved by all’.

Above: Ethelbert Meek’s headstone. Photo - Derek Bird.

Others who died included Sergeant Frank Pattinson, of the Canadian Army Dental Corps, who was born in London. England, in January 1889. He enlisted at Sewell, Ontario, in September 1915, and arrived in Britain in early January 1916. He was first posted to the Canadian Depot at Shorncliffe, Kent, before proceeding to France in late August 1917 to join the staff of the 3rd CSH. Just before leaving Britain he had been ‘brought to the notice of the Secretary of State for War for valuable services rendered con[nnected] with the war’.

Another victim was Captain John Smith Grant, who was heir to the Glenlivet Distillery in Banffshire, Scotland. He was born at Glenlivet in March 1893. Following his father’s death in 1911 the distillery was placed under trustees until he reached the age of 25 in March 1918, when he would assume control. Unfortunately, as he was serving in France and was killed two months later, he never had the opportunity to take over the distillery. He had been commissioned into the Territorial Force in February 1913 when he joined the 9th Battalion, Royal Scots and proceeded to France with them in early 1915. Transferring to the Royal Flying Corps in August 1916he qualified as a pilot in the following November. He joined 28 Squadron in France in August 1917 and claimed his first victory before the end of the month. He then sustained injuries to his left hand and face on 1 September when ‘he was destroying a detonator. Fuse on being ignited burnt more rapidly than it should the explosion occurring immediately the officer threw it away from him’. He was deemed ‘not to blame’ but spent nine days in hospital recovering. He was promoted to captain and appointed as a flight commander in October 1917. John Smith Grant was credited with downing a second aircraft on the Western Front in 1917, before his squadron was sent to Italy where he shot down three aircraft in the December to become an ‘ace’ with five victories. Returning to the Western Front in early 1918 he was posted to 70 Squadron and shot down his sixth and final aircraft on 23 May 1918; all his victories came while flying the Sopwith Camel. Six days later he was seriously wounded and taken to the 3rd CSH, but died in the bombing of the Doullens Citadel; according to his entry in De Ruvigny’s Roll of Honour he was the patient killed while on the operating table.

Above: Captain John Grant Smith’ and his headstone with the inscription ‘Death is the gate to life’. Photo - Derek Bird.

Sergeant-Major Charles Ward was born in London, Ontario, in January 1886. He enlisted in February 1915, declaring that he was an electrician and that he had seven years previous service with the Medical Corps. He arrived in England in April 1915, was promoted to staff sergeant in the June, before being sent to the Dardanelles with the 3rd CSH in the August. Returning to Britain in April 1916 the 3rd CSH was immediately sent to France. In July 1917 he was Mentioned in Dispatches and in the September was promoted to sergeant major and likely the most senior non-commissioned officer on the hospital’s staff. The following year he was awarded the Meritorious Service Medal, but this was not Gazetted until after his death (London Gazette Supplement 30750 Page 7178, 17 June 1918).

Another to die was the South African, Major Karl Siedle, of 174 Brigade, Royal Field Artillery. He was a keen sportsman and features in Nigel McCrery’s book, Final Wicket, as he played in a first-class cricket match between Natal and the MCC at the Pietermarizburg Ovalin December 1913. He did not, however, greatly trouble the scorers as he fell for a duck in his only innings and failed to bowl a wicket in his nine overs, but he did take one catch. He was Mentioned in Dispatches in January 1917, and was awarded the Military Cross in 1918: ‘For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty during a withdrawal. He remained out all day on a forward slope, directing the fire of his own and another battery with great effect on enemy troops and transport. He also sent back a great deal of the most valuable information’.

Above: Major Karl Siedle, MC, RFA.IWM Lives of the First World War

Above: Major Karl Siedle’s headstone with the inscription ‘Pain forgot in his pure presence joys eternal crown the fight’. Photo - Derek Bird.

Private Philippe Baillargeon has an interesting history and saw nearly all of his service with the 3rd CSH, both as a member of staff and as a patient. He had enlisted into the newly formed 3rd CSH at Windsor, Ontario, in mid-February 1915, declaring that he was a plumber and that he had served for two years in the Militia, even though he appears to have been only 18 years-old at the time. He sailed with the 3rd CSH to England in April 1915,and then in the August to Mudros to support the Gallipoli campaign. While at Mudros he was admitted to his own hospital on three occasions for diarrhoea; suspected typhoid and jaundice. The 3rd CSH was transferred back to Britain and then immediately to Doullens in April 1916. The rest of 1916 seems to have passed without problems, but Phillip Baillargeon was admitted with scabies in January 1917; with a sprained ankle in April, and then admitted with haemorrhoids in November 1917,and again in January 1918. Otherwise, he was awarded a good conduct badge in March 1917, and two months later awarded 14 days Field Punishment No.2 for being absent from a roll call and his billet! He was detached to the 3rd Canadian CCS in August 1917, but had returned to the 3rd CSH following his first bout of haemorrhoids. It is likely that he was one of those in the operating theatre when the bomb struck the building.

Above: Private Philippe Baillargeon’s headstone with the unusual French inscription ‘Ici repose le corps de Philippe Baillargeon tue en action par les bombes des Allemands’. Photo - Derek Bird.

Sergeant Arthur Lloyd was a 40 year-old labourer who had been born in Brighton, Sussex. He was another early member of the 3rd CSH when he enlisted in February 1915. He went with the 3rd CSH to Mudros in August 1915, where he was promoted to sergeant in the December. Until the time of his death he seems to have been a diligent member of the hospital staff and there are no illnesses or disciplinary matters on his records.

Private Frederick Metcalf was born in Gateshead-on-Tyne, England, in May 1888, and worked as a salesman with an address in Detroit, Michigan, USA, before enlisting into the CAMC in March 1916. He arrived in Liverpool in late July 1916 and was employed at the Duchess of Connaught’s Hospital at Taplow, Buckinghamshire, where a month later he was admitted for a few days suffering from lumbago. In August 1917 he was admitted again with a fractured finger following an incident with a cricket ball. He was then posted to the Canadian Depot at Shorncliffe, Kent, in the October, and onto the 3rd CSH at Doullens in February 1918.

Private Frank Minchin was born in Henley-on-Thames, England, in November 1888. He sailed to Canada on the RMS Virginian in April 1912. He was working as an electrical engineer when he enlisted in Edmonton in August 1916, and having poor vision in his right eye he probably wore spectacles. He arrived in Britain in the December and was employed at the West Cliff Hospital, Folkestone, until late May 1917. He was then transferred to the 14th Field Ambulance at Witley, Surrey, until early March 1918. A short period at the Canadian Depot, Shorncliffe, followed before proceeding to France at the end of the month. He was to only serve at the 3rd CSH for eight weeks before being killed.

Sergeant Robert Wallace was another early member of the 3rd CSH and he enlisted at the age of 21 in February 1915. He served with the hospital at Mudros and was promoted to corporal in December 1915. He then went to Doullens in April 1916, where he was promoted to sergeant in the September. In January 1917 he was admitted to the 39th General Hospital at Havre with ‘V.D.G. (S)’ and his records indicate that he forfeited his Field Pay and had a 50 cents per day stoppage of pay for 24 days while being treated. It therefore appears that he had acquired a sexually transmitted disease, quite possibly while on leave two months before. Between July and November 1917 he was detached to the 3rd Canadian CCS before returning to his parent unit, where he remained until killed.

Sergeant Gordon Wiley was born in Clearville, Ontario, in June 1895, and was another early member of the 3rd CSH having enlisted in February 1915 at the age of 19. He went to Mudros in the August, and then to France in April 1916. He was appointed lance corporal in May 1916; was promoted to corporal in the August, and then to sergeant in October 1917. His service seems to have not been blighted with illness or disciplinary matters, and he was even fortunate enough to be granted 14 days leave in Paris over Christmas 1917.

Private Ernest Glen was born in Leeds, Yorkshire, in October 1889. At the time of his enlistment into the 139th Battalion, Canadian Expeditionary Force, in mid-February 1916 he was working as a printer. Upon arrival in Britain in the October he was transferred to the 36th Battalion at West Sandling,but a month later transferred to the CAMC. After attendance at the CAMC Training School, he went to France to join the 3rd CSH in December 1916, where he continued to serve until his death on 30 May 1918.

Above: Soldiers searching through the ruins of the hospital shortly after it was bombed on 30 May 1918.No. 3 Stationary Hospital, Doullens, bombed by Germans; 3 Nursing Sisters and 2 Doctors Killed. June, 1918. Library and Archives Canada/Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Canada fonds/a003746

Above: The coffin of Lieutenant Abner Sage, American Medical Reserve Corps, being prepared for lowering into the grave. Funeral of three Canadian Sisters, one Canadian Doctor and one American Doctor who were killed in German air raid on 3rd Stationary Hospital, Doullens. May, 1918.Library and Archives Canada/Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Canada fonds/a002559

Above: Nurses and staff of the 3rd Canadian Stationary Hospital being address by Bishop Fallon of London, Ontario, at the funeral in Bagneux British Cemetery. Funeral of three Canadian Sisters, one Canadian Doctor and one American Doctor who were killed in German air raid on 3rd Stationary Hospital, Doullens. May, 1918. Library and Archives Canada/Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Canada fonds/a002557.

Above: Officers salute as the Last Post is played during the funeral at Bagneux British Cemetery. Funeral of three Canadian Sisters, one Canadian Doctor and one American Doctor who were killed in German air raid on 3rd Stationary Hospital, Doullens, May, 1918. Library and Archives Canada/Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Canada fonds/a002558.

Article contributed by Derek Bird