‘The 38th (Welsh) Division at Mametz Wood, July 1916. The Reasons for adverse criticism in the early historiography’

- Home

- World War I Articles

- ‘The 38th (Welsh) Division at Mametz Wood, July 1916. The Reasons for adverse criticism in the early historiography’

This article is derived from the research undertaken by Jon Williams' for his MA dissertation as part of the Britain and the First World War MA degree with the university of Wolverhampton for which he received a WFA MA Study Grant. Maps and photographs have been added.

Introduction

The historiography of the Somme Offensive is replete with accounts of that aspect of the Battle of Albert (1st-13th July 1916) which raged around Mametz Wood in the aftermath of the relative success of the first day of the offensive in that part of the British front, south of the Albert to Bapaume Road. Much of that historiography features the role of one of the last units of Kitchener’s ‘New Army’ to be formed, the 38th (Welsh) Division, and its conduct in the struggle for what was regarded as ‘such a difficult position to tackle…the original plans [for the Somme Offensive] did not contemplate any direct attack upon it at all’.

Unique in the context of the New Armies, the genesis of the 38th was embedded in Lloyd George’s Queen’s Hall speech to London’s Welsh diaspora in September 1914.(2) The concept of a ‘Welsh Army in the field’ was translated into aspirations of a Welsh Army Corps, of two divisions, recruited from within Wales, with Welsh officers, and with a National Executive Committee drawn from a wide range of Welsh civic society, including politicians, responsible for its implementation.(3) As a consequence, the identity of the 38th was rooted in the geography, language, socio-political, religious, and cultural history of Wales, and its emergent body of specifically national institutions and laws.(4)

The extent to which the uniqueness of the division was a factor in what it is now recognised as the unjustified criticism of its performance at Mametz Wood in 1916, formed the basis for my research and how the ‘Welshness’ of the division, the politics prevailing at the time and the extent of the alleged lack of military prowess demonstrated by the division, may have formed the basis for the criticism.

Mametz Wood and the Second Phase of the Somme Offensive

Analysis of the early days of the Somme Offensive reveals the importance of Mametz Wood as an objective in which General Sir Douglas Haig was heavily invested.(5)

Late on 1st July 1916 Haig ordered the 38th (Welsh) Division, under the command of Major-General Sir Ivor Phillips, DSO MP, from its positions with the GHQ reserve towards the area of operations of General Sir Henry Rawlinson’s Fourth Army on the Somme battlefront. (6) Haig then met with Rawlinson on 2nd July, directing him to ‘devote all his energies to capturing Fricourt and neighbouring villages…and then advance on the enemy’s second line’. (7)

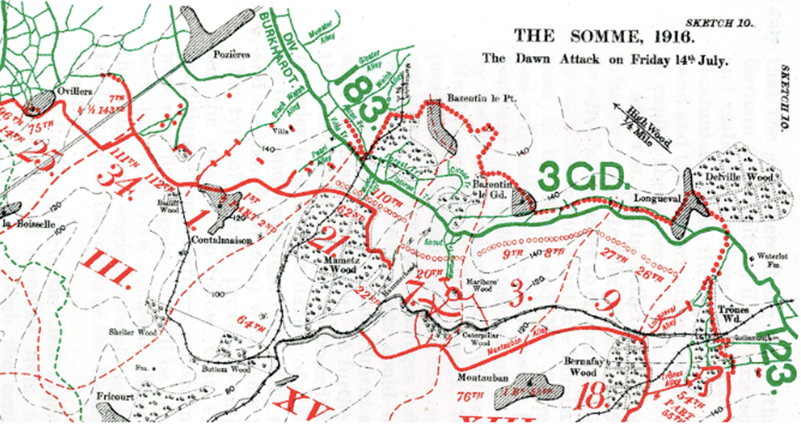

Haig noted how Rawlinson ‘did not seem to favour the scheme’. (8) Recognising this lack of enthusiasm for his plan, he instructed his Chief of Staff, Lt-General Sir Launcelot Kiggell, to draft a ‘written note to Rawlinson on the subject’. (9) Within the note, Haig’s intention to attack Mametz Wood was set out for the first time, in the context of launching an attack on ‘the main ridge between Bazentin-le grand wood and Longueval’, with the wood as the jumping off point. (10)

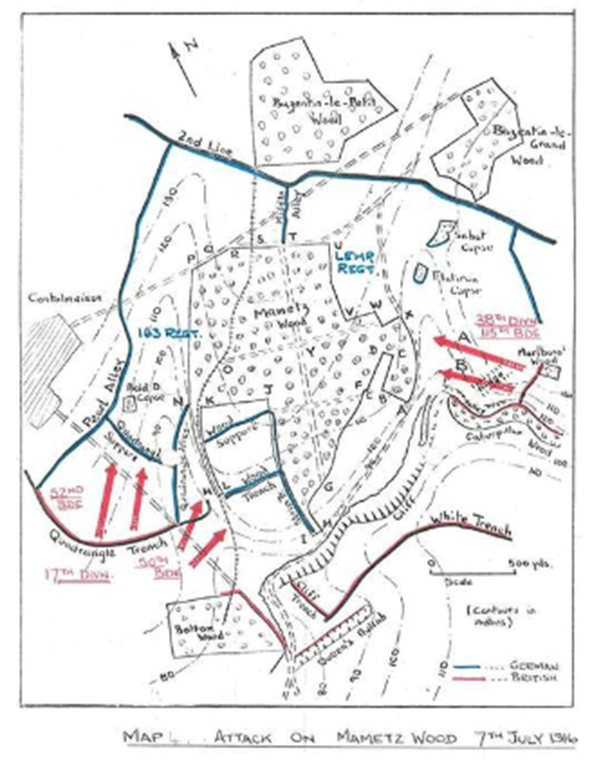

Responsibility for securing Mametz Wood and its environs would ultimately rest with XV Corps under the command of Lt-General Sir Henry Horne.(11) On 3rd July, preparations for the attack on the Bazentin Ridge and the German second line commenced, with XV Corps ordered to prepare to attack Mametz Wood. Haig regarded the occupation of Mametz Wood, and other woods in the vicinity as essential precursors to the attack on the German second line, and he impressed this upon Rawlinson again on 4th July. (13) Consequently a surprise attack on trenches to the south of Mametz Wood was ordered by Horne, commencing at midnight. The operation, by 17th and 7th divisions, delayed by heavy rain, was successful in part, securing objectives in front of Mametz Wood.(14) Horne, however, was under no illusions as to the magnitude of the task ahead of him, describing the wood as ‘a serious obstacle’.(15)

Haig again directed Rawlinson to capture the wood and to consolidate his position before attacking the German second line.(16) On 5th July, Rawlinson ordered XV Corps to ensure it had secured as much of Mametz Wood as possible by the morning of 7th July. (17)

Thus the 38th (Welsh) Division, untested in a major operation, found itself thrust into the febrile atmosphere of the fraught relationships between senior commanders who had promised much and had found their original plans derailed by the failures of the attacks of 1st July.

Despite Rawlinson’s orders, the first attempt to secure Mametz Wood per se, by formations of XV Corps, was not undertaken until the morning of 7th July, when battalions of the 17th Division’s 52 Brigade unsuccessfully assaulted positions south-west of Mametz Wood in a night attack, with the 38th’s 115 Brigade separately attacking the Hammerhead area of the eastern part of the wood in daylight later that morning. (18) The attackers from the 38th were brutally cut down by German machine gun fire, enfilading from the right flank of the advance as well as from within Mametz Wood itself. The plan for the attack had emanated from Horne and XV Corps, who refused to countenance any change in the disposition of the 38th’s attacking battalions, despite the commander of 115 Brigade pointing out the dangers of the enfilade faced in crossing the open ground in front of the wood. (19)

Haig, undoubtedly reacting to information supplied by XV Corps and its commander, accused the 38th of having ‘not advanced with determination to the attack’, recording grossly underestimated casualty figures for the 38th in his diary.(20)

The importance of Mametz Wood to the continuation of the entire Somme Offensive was reiterated by Haig in yet another visit to Rawlinson on 8th July, the day after the 38th Division’s first, abortive attack, on the wood. Also on 8th July, in a note to the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Haig outlined how the advance on the Bazentin Ridge had not proceeded ‘fast enough to deprive them [German forces] of the possibility of bringing up reserves’ but stressing his optimism of capturing the ridge.(22)

On 9th July Haig visited Rawlinson again to urge him to capture Mametz Wood, before visiting Horne at his Corps HQ, to similarly impress the same urgency on him. Rawlinson records in his journal his continuing doubts over Haig’s insistence Mametz Wood is under British control prior to launching the next phase of the offensive.(23)

As Colin Hughes explained, there was a fundamental ‘lack of understanding’ between Haig and Rawlinson over the importance of Mametz Wood, Haig desiring the attack on the Bazentin Ridge being launched from Mametz Wood, with Rawlinson favouring a frontal attack.(24) Robin Prior and Trevor Wilson are more forthright, accusing both Rawlinson and Horne of failing to act expeditiously in seeking to secure Mametz Wood, ordering repeated unsupported attacks with little regard of the consequences for the men conducting them.(25)

The ‘Welsh’ Element

Clive Hughes observed, the British military establishment subjected the 38th to a more longer lasting and unsympathetic reception than given to any other New Army division, a direct consequence of its connections with Lloyd George. (26) It is argued one cause of this was the absence of respect for the Welsh soldier amongst senior British commanders.

Lieutenant-Colonel Charles a Court Repington, military correspondent of The Times and the ‘single most significant military journalist of the period…impeccably well-connected and a highly influential military thinker’ wrote disparagingly, the Welsh soldier ‘was a scout by nature’ not inclined to ‘organisation and discipline’. (27) Kitchener also manifested a clear bias, confiding to Asquith how ‘purely Welsh regiments’ are ‘not to be trusted’, Welsh soldiers being ‘always wild and insubordinate’, requiring to be ‘stiffened by a strong infusion of English or Scotch’. (28)

This disparaging attitude to the division is clearly visible in the way Haig, Rawlinson and Horne refer to the formation in their respective diaries and journals, as set out below, repeated in the press communique published as the attack on the Bazentin Ridge commenced, which gave the credit for the capture of Mametz Wood to ‘England alone’ with ‘English lads from the North…who fought on the way to Contalmaison and took this stronghold of the woodlands’. (29)

Haig, the generals, and the criticism of the 38th

During the evening of 5th July, as 38th division relieved 7th division in the positions to the south-east of Mametz Wood, Horne met with Phillips and Major-General Thomas Pilcher, commanding 17th Division, both of whom he would subsequently remove from their commands after the failure of their respective divisions to successfully capture Mametz Wood in attacks on 7th and 8th July. Haig learned of this on his visit to Rawlinson on 9th July, giving retrospective approval to Horne’s actions. (30)

The attacks for which Phillips and Pilcher were held responsible were directed, not by themselves and their respective Staffs, but by Horne and the Staff of XV Corps. The level of control over this attack by Horne personally, and his Staff, is documented in the XV Corps War Diary with entries clearly showing how Horne was giving orders as to how the attack should proceed.Two further attacks ordered by Horne and XV Corps on 8th and 9th July did not take place, amongst much confusion between Corps, Division and Brigadier-General Price-Davies’s 113th Brigade, which had failed to even get to the start line. The XV Corps War Diary shows responsibility for organising the attack rested with Price-Davies, as OC 113th Brigade, reading, ‘Place [of attack] must be chosen by the Commander of the 113th Brigade…who should carry out the raid and fix the exact point. Neither Corps nor Division, not being on the spot, could fix this.’ (33)

Phillips had already asked Price-Davies for a ‘Special Report’ as to why he had failed to ensure his brigade had conducted its orders and Horne and XV Corps were aware of this when he was removed from command. (34)

On 9th July, having installed Major-General Watts of 7th Division as temporary CO of the 38th, prior to an attack by the entire division, Haig provided ‘the troops of the Welsh Division the opportunity offered them of serving their King and Country at a critical period and earning for themselves great glory and distinction’. (35) On 11th July, following the capture of the wood after almost two days of the bitterest hand-to-hand fighting, a message from Haig to the 38th read, ‘The C-in-C desires to express his appreciation to all ranks of the 38th (Welch) Division for the splendid response made to his appeal for a special effort yesterday’. (36)

Haig’s endorsement of the success of the 38th was not entirely sincere. Late on 10th July, having been informed how two brigades of the 38th had entered the wood, their battalions engaged in clearing it of Germans, Haig made it clear he believed the success was purely the result of Watts, a ‘good commander’, despite having been in command for less than twenty-four hours, as opposed, presumably to Phillips. (37) Watts had previously been described by Haig, only weeks earlier as ‘a distinctly stupid man and lacks imagination’, albeit with the caveat he was ‘a hard fighter, leader of men and inspires confidence in all both above and below’. (38)

Horne, whilst conceding the difficulties of wood fighting was a factor in the time taken to capture the wood, also attributed the success of to the appointment of Watts, ‘a splendid fellow. The best general I have,’ crediting his ‘old friends,’ of the 7th Division, rather than ‘the new hands’, the 38th, with the success.(39)

The paucity of this view is laid bare by Watts’ second-in-command of 7th Division, Brigadier-General Sir Charles Bonham-Carter, who accompanied him on taking command of the 38th and who credited that division’s own brigade commanders and its GSO 1, Lt-Colonel H. E. ap Rhys-Pryce, with engineering the success of the capture of Mametz Wood. (40)

In Sir Douglas Haig’s Despatches, (1919), a compilation of his reports to the War Office following his appointment as CIC in December 1915, Haig was critical of the 38th stating ‘Meanwhile Mametz Wood had been entirely cleared of the enemy (by 21st Division)’. (41) In his introduction to Lieutenant-Colonel Munby’s A History of the 38th (Welsh) Division, (1920), Haig omitted any reference to the division’s efforts at Mametz Wood, whilst referring to its conduct at the third Battle of Ypres in 1917 and at Pozieres in 1918 as allowing ‘on both occasions, all who fought with the 38th Division to look back with legitimate pride’.(42) He allowed access to his personal papers for the writing of Sir Douglas Haig’s Command (1922), his defence of his own conduct during the war, and an undisguised attack on Lloyd George, in which the 38th was held responsible for the failure of the entire Somme Offensive. (43)

All three publications were drafted, edited, or written by Haig’s wartime personal secretary, Lieutenant-Colonel J. H. Boraston, with whom he maintained a close working relationship after the war, and who drafted many of the speeches, articles and other material published or used by Haig in his post-war activities.(44)

Haig’s animus towards the 38th (Welsh) Division must have been specific to the formation because, as Gary Sheffield points out, Haig ‘admired the wartime volunteers and conscripts’ and the New Army divisions were akin to the ‘national army’ he had foreseen in 1906 when working on the reforms to the Army.(45) His apparent contempt for the conduct of the 38th would be maintained for the duration of the war and beyond, refusing to give any credit whatsoever to the division for its actions in securing Mametz Wood, denying it did so when praising it for having done in August 1918. (46)

Notwithstanding the Regular Army’s antipathy towards Welsh soldiers, and Haig’s own animus towards Lloyd George, the question as to why he would seek to deny the laurels of victory to one New Army division has not been explained in the historiography.

Both Rawlinson and Horne would take a similar approach in their attitudes towards the 38th.

In his journal, Rawlinson on July 10th specifically credits the 38th with ‘capturing practically the whole of Mametz Wood’.(47) Barely four days later however, he sought to prevent any credit being given to the ‘Welshmen’. In two letters, the first, to Sir William Robertson, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS) he wrote, ‘I only write a line to say how splendidly our troops have done. Only one Division, the 38th (Welshmen) turned out badly’. He provided the same explanation for the delay at Mametz Wood to the British Army’s Director of Recruiting, Lord Derby.(48)

This was not the first time Rawlinson had sought to blame subordinates for his own failures. At Neuve-Chapelle in 1915 he petitioned Haig to remove the OC of 8th Division. When the individual made his case to GHQ, Rawlinson was forced to back down and admit he had been in the wrong. Haig dissuaded the then C-I-C, Sir John French, from removing Rawlinson from command, and he received a warning.(49) Haig later described Rawlinson as lacking any loyalty to any of his subordinates. (50)

In his The Real War, 1914-1918 (1930), Basil Liddell Hart, a veteran of The Somme, acknowledged how the delay in capturing Mametz Wood impacted the second-phase attack, without blaming the 38th, whilst noting the adverse impact Rawlinson and Horne, had on matters.(51)

Animosity towards Phillips in the ranks of the senior officers of the BEF was primarily for his relationship with Lloyd George, but also because of his status as a ‘dug out.’ He was, in the eyes of the generals of the BEF, nothing more than a ‘jumped up Indian Army major who had no right to a divisional command.’ He was dispensable and Welsh troops under his command, became tainted, by the ‘unjust slurs which army gossip laid on him.’(53)

A further explanation for the animus towards Phillips and his division may be found in another case of military mismanagement. In his unpublished thesis, The Men Who Planned the War, Paul Harris describes how, in a speech to the House of Lords in November 1915, Liberal Peer Viscount St. Davids, attributed ‘bad Staff work’ for the BEF’s failure at the Battle of Loos in September 1915, blaming the incompetence of senior officers for the army’s inability to defeat the Germans. (54) Many of those involved in directing the Loos engagement commanded during the Somme Offensive, including Haig, Rawlinson, and Horne. All formed the command structure under which the 38th operated on the Western Front, and perhaps a factor in their collective animosity towards the commander of the 38th and his subsequent treatment on The Somme, was that St David’s was Ivor Phillips’s older brother. (55)

Rawlinson, under significant pressure from Haig to launch the offensive on the German second-line defences, put pressure on Horne, who sought to blame the ‘New Army troops’ for the delays. (56)

Having been set the task by Rawlinson, Horne, as Tim Travers has described, came up against the realities of contemporary warfare, where the traditions and expectations of the Army diverged under the pressure of the emerging war of attrition. (57) Don Farr is explicit in his condemnation of Horne, simply out of his depth in commanding a battlefield in such circumstances as on the Somme. He required scapegoats for his inability to manage his resources effectively and in the ranks of the senior generals of the BEF on the Western Front, deflection and cover-up was the default position.(58) Phillips was removed and the taint of scandal that went with his removal stuck to the 38th.

Haig failed in terms of what he had promised the Somme Offensive would achieve. As Gary Sheffield opined, Haig’s plan was ‘too ambitious’ for the minimally trained and naïve New Army battalions, and he was unable or unwilling to manage Rawlinson who sought to undermine his operational concept for the offensive.(59) The repercussions of the failure to capture Mametz Wood fell on Rawlinson, as the architect of both the main Somme Offensive, and the attack on the Bazentin Ridge on 14th July. In much the same way Haig failed to control him, Rawlinson, failed to manage Horne.(60) As such it was expedient for all the commanders to resort to what Travers describes as ‘the dishonest preservation of individual and collective reputations’.(61) This was achieved by blaming the 38th (Welsh) Division for the failure to capture the wood in a timely fashion and denying it the plaudits deserved when it ultimately secured the objective.

The Price-Davies Reports (62)

The most damaging source of the adverse criticism of the division came from within its own ranks, and undoubtedly flourished as part of the gossip within the BEF and beyond. Commanding the division’s 113th Brigade, Llewellyn Alberic Emilius Price-Davies was described by Arthur Conan Doyle as ‘a young brigadier who is more likely to win honour than decorations, since he started the War with both a VC and DSO.’(63) Llewellyn Wyn Griffiths, who served under him, later described him as ‘the second most stupid soldier I met…as he was too dull to be frightened’.(64)He was a martinet, more concerned with the height of a trench parapet than the welfare of his men. (65)

A Regular Army officer who had served with Haig and the other senior generals in the war in South Africa, where he won his VC, Price-Davies was serving in the War Office on the outbreak of war, with his brother-in-law, future Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson.(66) As the BEF mobilised Price-Davies took up the position of GSO3 in the rank of Captain, on the staff of 2nd Division, part of the Aldershot Command under the then Lt-General Douglas Haig.(67) In 1915, prior to the 38th’s mobilisation to France he was made Brigadier-General commanding the 113th Brigade, one of the ‘younger, fitter men, with more experience of modern war’, who replaced a number of the division’s original officers.(68) He was known to his contemporaries as ‘Mary’. (69)

Price-Davies’s actions in the aftermath of the actions at Mametz Wood provided the basis for the subsequent allegations that the 38th had not conducted themselves in the manner expected of the British soldier, that the division had ‘bolted’ and the reason for it being removed from the Somme Offensive. (70)

On 16th July, Price-Davies wrote to his wife informing her of a visit from Haig who, ‘congratulated me on our success at Mametz’. His activities that day were not limited to writing to his wife, however. The day of Haig’s visit he submitted a report which condemned the 38th for lacking courage at Mametz Wood.(71) In two paragraphs, he described a ‘disgraceful panic,’ ‘indisciplined’ firing and how ‘A few stout-hearted Germans would have stampeded the whole of the troops in the wood.’ (72)

Seemingly having reflected on events, Price-Davies submitted a second report the following day, in which he contextualised his previous damning comments by referring to the same ‘gallant actions’ he had mentioned to his wife. Whatever his reasons, he again repeated the underlying accusation of the ‘discreditable behaviour of the men of the Division who fled in panic at about 8.45 p.m. on July 10th.’ (73)

On 19th July he wrote to his wife again about events at Mametz Wood, categorising his experience as ‘not so terrible’. Perhaps having second thoughts over his report, he wrote ‘I think my people did better than I thought at first, many gallant actions have come to light.’ (74)

Price-Davies’s reports were damning of the division, and there can be no doubt they provided a significant contribution to the narrative which emerged, of the Welshmen running from the fight. Likely as not, it formed the primary source of the ‘common talk’ in the B. E.F. that 38th Division had “bolted”’ as claimed by Drake-Brockman in his response to the Official Historian in 1930.(75) There can be no doubt the reports were seen by Haig, but given their close personal and professional relationship, Price-Davies being a former member of Haig’s Staff in 1914, it is not unreasonable to believe he discussed his experiences in Mametz Wood with Haig during his visit. Haig’s philosophy of command and his belief in military discipline and unquestioning obedience to orders defined his command of the BEF.(76) Without doubt Price-Davies’s revelations, whenever they came to his attention, allied with the failure of the second phase attack on Bazentin Ridge, would have affronted his military sensibilities, providing an explanation for Haig’s coolness towards the 38th and his ongoing refusal to acknowledge the achievements of the division at Mametz Wood for the rest of the war, and account for the omission of the engagement in Munby’s History. (77)

Price-Davies’s retreat from his initial condemnation of his men is obvious from his correspondence with the Official Historian. In 1930, he simply states he ‘soon got involved with parties who were retreating through the wood and whom I had the greatest difficulty in controlling’.(78) However, his comments in the two reports may well have been seen by Edmonds suggested by reference in the Official History to ‘much indiscriminate firing, and some panicking of men to the rear’ in the account of events at Mametz Wood.(79) It is also the scenario proffered by Drake-Brockman to Edmonds in his vitriolic correspondence of 1930, he having spent almost a year on the staff of the 38th from 9th July 1916. (80)

Yet, the Brigade-Major of the 113th Brigade, J. C. MacDougall-Stewart, in his correspondence with Edmonds, painted a different picture, recognising the inevitable chaos of the close-quarter fighting in the wood, and commenting ‘however dazed and shaken these Welshmen were by their experiences in the wood, none of the Battalion ever became demoralised. Disorder there was bound to be.’ (81)

Whether Haig played any part in Price-Davies submitting such scathing reports remains unknown. Having been required by Phillips to account for his brigade’s failure to launch two attacks as ordered, he may have sought to deflect responsibility for his own personal failings by exaggerating alleged failures in the rank and file of the division as Rawlinson and Horne sought to do. In his diary he confesses to feeling ‘very guilty’ over Phillips’ removal, admitting it came after the failure of ‘an enterprise’ by one of his own battalions. (82)

Conclusion

Much, if not all the criticism of the 38th at Mametz Wood emanated, not unsurprisingly, from senior officers of the Regular Army within the BEF. The importance attached to Mametz Wood by Haig in his plans for the continuation of the Somme Offensive is clearly demonstrated by his continual exhorting of Rawlinson during this period. The fact the attack on the Bazentin Ridge was not proceeding as quickly as Haig had envisaged may go some way to explaining the vitriol and longevity in what became a personal animus towards the 38th (Welsh) Division in the aftermath of the capture of Mametz Wood, and the reasons for senior officers of the Regular Army to join with him in denigrating the division.

That criticism was underscored by a variety of additional factors including the alleged ‘politicisation’ of the division because of Lloyd George’s close relationship with, and role in, the appointment of, its commander, Major-General Sir Ivor Phillips MP, DSO, together with the general aversion of the Regular Army towards New Army formations and an antipathy towards Welsh soldiers in general.

The motivation behind the promulgation of the narrative of failure which came to surround the 38th (Welsh) Division in the aftermath of the attacks on Mametz Wood was initially professional self-preservation. That it would later become a political weapon is the responsibility of Haig, who became ‘affronted by Lloyd George’s claim, he had won the war.’ (83) In addition, at least according to Lady Haig, her husband regarded Lloyd George as having ‘belittled’ the British Army.(84)

Captain Llewellyn-Evans, MC, Royal Welsh Fusiliers, summarised Mametz Wood thus, ‘The story of Mametz and its comparative failure is not one of wavering men or faint hearts; but one of bad staff work, inadequate maps, lack of general co-ordination and nature’s elements at their worst’ (85)

Footnotes:

1. Birmingham Daily Post, 14th July 1916, Press Association

2. The Times, September 20th, 1914

3. Welsh Army Corps, 1914-1919: Report of the Executive Committee, (Cardiff: Western Mail 1921), pp. 3-4

4. John Davies, A History of Wales, (London: Penguin, 1993), p.398

5. Captain Wilfred Miles, History of the Great War Based on Official Documents: Military Operations France & Belgium, 1916, 2nd July 1916 to the end of the Battles of the Somme, (London: HMSO, 1938), p. 9.

6. Haig Diary 1st July 1916, National Library of Scotland.

7. Haig Diary 2nd July 1916, National Library of Scotland.

8. Haig Diary 2nd July 1916, National Library of Scotland

9. Haig Diary 2nd July 1916 National Library of Scotland

10. LHCMA Ref Kiggell 4/28 Personal Papers of General Sir Launcelot Kiggell, note dated 2nd July 1916 to Rawlinson ‘confirming the gist of what the Commander-in-Chief said at his interview with you today’.

11. Captain Wilfred Miles, Official History of the Great War, p. 10.

12. TNA, WO95/431 Fourth Army Operational Order 32/3/16(G) dated 3rd July 1916

13. Haig Diary 4th July 1916, National Library of Scotland

14. Michael Renshaw, Mametz Wood, (Barnsley: Pen & Sword, 2006), pp. 33-44

15. Letter from Horne to his wife, dated 4th July 1916, Private Papers of General Lord Horne of Stirkoke, IWM

16. Haig Diary 8th July 1916, National Library of Scotland

17. TNA, WO95/431 Fourth Army Operational Order 32/3/16(G) dated 5th July 1916

18. Miles, Official History of the Great War, pp. 28-36.

19. NLW Penralley Papers Ref. 984b, ‘Account of the early stages of the battle for Mametz Wood in the handwriting of Brigadier-General Horatio James Evans (photocopy) & Llewellyn Wyn Griffith, Up to Mametz, (London: Faber & Faber, 1931), p.101

20. Haig Diary 8th July 1916, National Library of Scotland

21. Haig Diary 8th July 1916, National Library of Scotland

22. Extract from a letter from C-in-C to CIGS dated 8th July 1916 and copied to General H Rawlinson, RWLN 1/6 Rawlinson Papers, Churchill Archives Centre, Churchill College Cambridge.

23. Rawlinson Journal 9th July 1916, RWLN 1/5 Rawlinson Papers, Churchill Archives Centre, Churchill College, Cambridge.

24. Colin Hughes, Mametz-Lloyd George’s ‘Welsh Army’ at the Battle of the Somme, (Gerrards Cross: Orion Press, 1982), pp. 74-75

25. Robin Prior & Trevor Wilson, The Somme, (Harvard: Yale University Press, 2005), pp. 125-126

26. Clive Hughes, ‘The New Armies,’ in Ian F. W. Beckett & Keith Simpson (eds.), A Nation in Arms, A Social Study of the British Army in the First World War, (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1985), p. 120.

27. Gary Sheffield, review of A. J. A. Morris ‘Reporting the First World War: Charles Repington, The Times and the Great War’ (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015) in British Journal for Military History, Vol. 3, Issue 2, February 2017, pp. 139-142, & Mike Benbough-Jackson, ‘Five-Foot-Five Nation: Size, Wales and the Great War’, in Welsh History Review/Cylchgrawn Hanes Cymru, Vol. 28, 4, (2017), p.633.

28. Letter Asquith to Venetia Stanley 30th October 1914, in Michael & Eleanor Brock, (eds.), H. H. Asquith:

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37. Haig Diary 10th July 1916, National Library of Scotland

38. Haig Diary 9th May 1916, National Library of Scotland

39. IWM, Papers of General Lord Horne of Stirkoke, Letter to Horne’s wife dated 12th July 1916

40. CAC Ref BHCT9 Papers of General Sir Charles Bonham-Carter, Unpublished autobiography, 1954-1955, p.15.

41. J. H. Boraston (ed.), Sir Douglas Haig’s Despatches, 1914-18, (London: J. M. Dent & Sons, 1919

42. Field-Marshal Earl Haig, ‘Introduction’ dated 26th November 1919, in Lieutenant-Colonel J. E. Munby, (ed), A History of the 38th (Welsh) Division by the GSO 1’s of the Division, (London: Hugh Rees Ltd., 1920)

43. A. B Dewar & J. H. Boraston, Sir Douglas Haig’s Command: December 19, 1915, to November 11, 1918, (London: Constable & Company Ltd., 1922)

44. IWM, The personal papers and correspondence of Colonel J. H. Boraston compiled in his personal capacity as personal secretary to Field-Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, Documents 29135a, Box No. 71/13/1

45. Gary Sheffield, Douglas Haig: From the Somme to Victory, (London: Aurum Press, 2011), pp. 143 & 148.

46. Haig Diary 19th December 1916 & 18th August 1918, National Library of Scotland

47.

64. Llewellyn Wyn Griffith, Up to Mametz, (London: Faber & Faber, 1931), p.132

65. Llewellyn Wyn Griffith, in Up to Mametz and Beyond, Jonathan Riley, (ed.), (Barnsley: Pen & Sword, 2021), p.144

66. Peter Robinson, (ed.), The Letters of Major General Price-Davies, VC, CB, CMG, DSO: From Captain to Major General, 1914-18, (Stroud: Spellmount, 2013), p. 11

67. Ibid, p. 15

68. Jonathan Riley, Ghosts of Old Companions: Lloyd George’s Welsh Army, the Kaiser’s Reichscheer and the Battle for Mametz Wood, 1914-1916, (Helion & Co. 2019) p. 110.

69. Ibid, p. 7

70. TNA CAB 45-188 Letter from Major G. P. I. Drake-Brockman to Brigadier-General Sir James Edmonds, p.5

71. Wrexham County Archive, Papers relating to Mametz Wood, The Letters of Brigadier-General Price-Davies VC DSO, Commander 113th Infantry Brigade 38th (Welsh) Division, August 1914-28th December 1916, A Transcription of personal letters to his family. Letter dated 16th July 1916

72. TNA WO95-2552-1, 113th Brigade, 38th (Welsh) Division War Diary Appendix 20 Confidential Report Marked Secret dated 16th July 1916

73. TNA WO95-2552-1 113th Brigade, 38th (Welsh) Division War Diary, Appendix 26 ‘Confidential Report Marked Secret’ dated 20th July 1916

74. Letter dated 19th July 1916, Brigadier-General Price-Davies to his wife in Peter Robinson, (ed.), The Letters of Major General Price-Davies, VC, CB, CMG, DSO: From Captain to Major General, 1914-18, (Stroud: Spellmount, 2013), pp. 111-112

75.

76.

77.

78.

79.

80.

81.

82.

83. Keith Simpson, ‘The Reputation of Sir Douglas Haig,’ in Brian Bond, (ed), The First World War and British Military History, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991, p. 144.

84. Western Mail 4th December 1936, Review of ‘The Man I Knew’, by Lady Haig

85. Western Mail, 6th July 1935