Donald Where’s Your Troosers?

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Donald Where’s Your Troosers?

Once the stalemate of trench warfare set in during the autumn of 1914 it was not long before the British Expeditionary Force established a policy of dominating No Man’s Land. This may have been through patrols quietly crossing No Man’s Land to try and gather some intelligence on the enemy’s positions, or it could be in the form of a raid.

Above: 1/8th King’s (Liverpool) Regiment raiding party following a raid at Wailly, France, on the night of 17/18 April 1916. (IWM Q510).

Raids could be small affairs, or at the other end of the scale one staged on Vimy Ridge by the Canadian 4th Division in the early hours of 1 March 1917 was exceptionally large. The Canadians used four battalions (54th, 72nd, 73rd and 75th) to provide 1,700 men for the raid. Unfortunately gas released nearly three hours before the raid drifted back into their trenches. Unfortunately the noise made by the affected Canadians alerted the Germans who opened a fierce artillery bombardment causing heavy casualties. British shells dropping short also caused casualties when the Canadians later advanced through No Man’s Land. The German wire then proved to be a major obstacle, with casualties mounting further as the Canadians tried to cut their way through in the face of a hail of machine gun and rifle fire. The raid was a complete failure that cost almost 700 casualties, including two battalion commanders being killed. Such was the carnage that a local truce was arranged on the 3rd to allow the bodies of the dead to be recovered; the Germans agreeing to carry them to the half-way point of No Man’s Land, from where the Canadians would take them back to their own lines.

The 51st (Highland) Division (divisional sign above) also undertook its fair share of raiding and after a very strenuous period in early 1918, when they suffered over 7,000 casualties in the German Offensive near Bapaume, and immediately afterwards at the Battle of the Lys, they were finally withdrawn for a short period of rest. Then, on 6 May, they took over the line just north of Arras; an area well-known to those who had been with the division in 1916 and 1917. Now a relatively quiet sector the division spent the next weeks working on defences, while sending out at least six patrols nightly to gather intelligence and dominate No Man’s Land. One very successful patrol was on the night of 13-14 June when Lieutenant Astley and four men of the 6th (Morayshire) Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders, surprised a seven-man German patrol and captured them all.

Above: A 6th (Morayshire) Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders, raiding party at Armentières, France, following a raid on 15 September 1916. (Derek Bird).

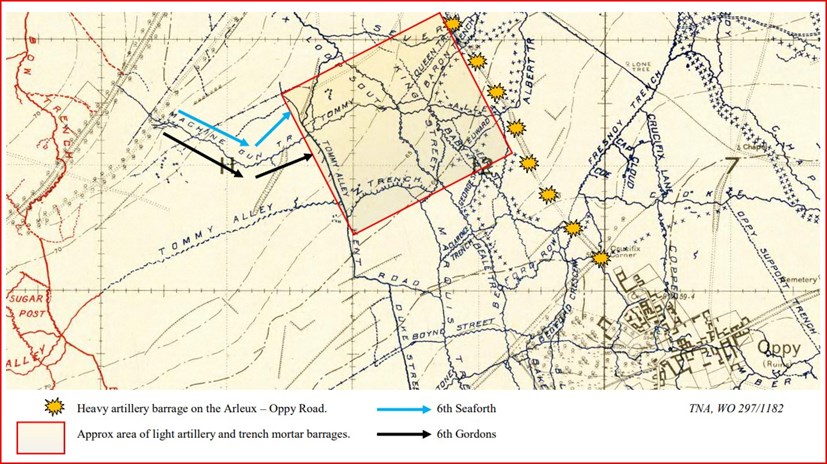

During their time near Arras the Highland Division also mounted a number of trench raids of varying size and results. The afternoon and evening of 8 July 1918 were recorded as being ‘very hot and muggy with heavy thunderclouds’, but nevertheless a raid planned for the early hours of the 9th went ahead. A combined force of 6th Seaforth and 6th Gordon Highlanders, led by Lieutenants Muir and Reid (Seaforth and Gordons respectively), comprising six sections of Seaforth and seven of Gordons, totalling almost 100 men, was gathered and briefed. They were to enter the German lines north-west of Oppy with the aim of ‘obtaining an identification’ and ‘killing or capturing as many of the enemy as possible’.

The plan was for a 40-minute artillery and trench mortar barrage on the German positions to start at 12:30 a.m. At Zero hour (1:10 a.m.) the infantry were to advance either side of Machine Gun Trench under the cover of a reduced barrage – the Seaforth on the north side and the Gordons on the south side. The barrage would then lift off the German front line at Zero + 2 minutes as the raiders were due to approach it.

Above: Trench map of raid by 6th Seaforth Highlanders and 6th Gordon Highlanders, 9 July 1918.

Above: The area today with the above trench map superimposed (via the WFA's TrenchMapper portal)

All went well with both the assembly in No Man’s Land and the initial advance, however, the Highlanders soon encountered uncut wire and trying to find gaps were greatly hampered by the very dark night. The Seaforth party veered slightly too far to their left and encountered some of the enemy who engaged them in a bombing fight. Lieutenant Muir tried to work his way around the German’s flank when, with the planned 20 minutes gone, the recall signal went up and he began to withdraw his men. The Gordons managed to get men into Kent Road Trench but not encountering any Germans could not obtain any identification; the only item reported as being brought back by the raiders was a ‘notice board’.

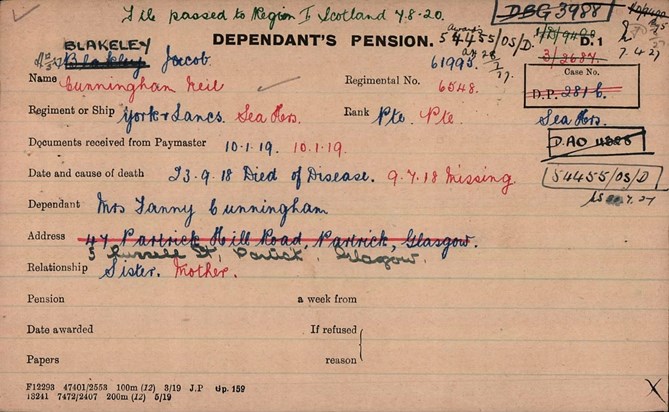

All the raiders and covering parties were back in the British trenches by 2:30 a.m. having only suffered a few casualties. Accounts vary as some include casualties in the covering parties, but it appears that about eight men were wounded in total. The 6th Seaforth also had two men missing, one of whom had in fact been wounded and made his way back to British lines the following night. The other was almost certainly 20 year-old Private Neil Cunningham, who died on the 9th and is now buried in Douai British Cemetery.

Above: The Pension Record Card of Neil Cunningham and (below) Douai British Cemetery, where he is buried.

After the raid the Gordons felt sufficiently disgruntled at the attitude of authority to note in their War Diary that ‘Corps refused sanction of an issue of rum for the men when they came out, but a good breakfast and a whiskey [sic] ration was provided by the battalion’.

This, on the face of it, seems a typical large-scale raid like hundreds of others that took place during the course of the war, however, there is one aspect that makes it possibly unique in the annals of trench raiding, as recorded in the 6th Gordon’s history:

A raid made by seven sections of the 6th Battalion and six sections of the 6th Seaforth Highlanders on 9th July, was remarkable for the extraordinary dress of the men. The kilt was discarded. Faces, hands, and legs were blackened. A few men wore shorts, a few wore service-dress jackets, but a number went over wearing only a shirt, with equipment above. The parties assembled in a sharp thunderstorm with vivid lightning and heavy rain. They reached their objective – Kent Road – after encountering many difficulties with the wire, but no enemy could be found, and the raiders returned with only one man slightly wounded. Whether the disappearance of the enemy was caused by the warning given by the wire, or by the strange apparitions bearing down upon them, has never been ascertained.

Article contributed by Derek Bird

Further reading:

F.W. Bewsher. The History of the 51st (Highland) Division 1914-1918, (Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons, 1921).

Derek Bird. The Spirit of the Troops is Excellent: The 6th (Morayshire) Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders in the Great War1914-1919, (Garmouth: Birdbrain Books, 2008)

D Mackenzie. The Sixth Gordons in France and Flanders, (Aberdeen: Rosemount Press, 1922).

Jonathan Nicholls. Cheerful Sacrifice,(Barnsley: Leo Cooper 1990).