The 'Dead Enigma': Hedd Wyn and Francis Ledwidge and the Welsh National Eisteddfod

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The 'Dead Enigma': Hedd Wyn and Francis Ledwidge and the Welsh National Eisteddfod

In September 1917, the Welsh National Eisteddfod was held at Birkenhead Park, on the Wirral, only the third time it had been held outside the Principality.

A huge crowd, including the Prime Minister David Lloyd George himself a Welsh language speaker, had gathered to take part in this annual celebration of Welsh culture and language.

The highlight of the festival was to take place on 6 September when the name of the winning poem along with its author, would be announced to the expectant audience.

This was normally followed by the 'chairing of the bard' ceremony when the winning poet would make his way through the crowd to take his seat in the bardic chair, a beautiful, wooden chair especially carved for each Eisteddfod.

At the 1917 festival, it was announced that the winning poem was entitled 'YnArwr (The Hero)' and that the winning author had written under the pseudonym Fleur de Lys.

The tradition was for trumpets to sound a fanfare to invite the winner to make themselves known. Three times they sounded; three times the Archdruid called out the nom de plume of the winning bard but when no one came forward, he then solemnly announced to the silenced audience that the winning poet, Ellis Humphrey Evans better known by his bardic name of Hedd Wyn, had been killed in action six weeks earlier.

The chair, expertly carved by Belgian refugee Eugeen Vanfleteren, was draped in a black shroud; it later made an emotional journey to the family farm where it can still be seen today.

Above: The Black Chair of the 1917 Eisteddfod.

Above: This is now in the homestead at Trawsfynyddand Hedd Wyn’s home in Trawsfynydd (Photos – author)

Wyn had been killed early on the 31 July, the opening day of what became known as the Third Battle of Ypres, now better known as Passchendaele; he was one of over 9000 British troops killed in the first three days of the battle.

His regiment, 15th (Service) Battalion Royal Welch Fusiliers was taking part in the assault on Pilckem Ridge when he was killed by a shell fragment.

Above - The Welsh poet Ellis Humphrey Evans better known as Head Wyn (Photo: Visit Wales)

Wyn had written his poem in France and posted it on 15 July, the very day that the battalion had begun its march to the front.

He had begun writing at the age of 12, and by the time of his death, was already an established poet in the Welsh language having already won six bardic chairs at regional competitions.

Like many of those who enlisted, Wyn was not a natural soldier; in fact, when war was declared, he was working as a shepherd on the family farm at Trawsfynydd, in a remote area of north Wales. He was a Welsh nationalist and a Christian pacifist - the translation of his bardic name is “Blessed peace” - an ideal that he followed when he initially refused to sign up for the war, arguing that his work was contributing to the war effort; indeed farm work was regarded as a reserve occupation.

However early in 1916, the war arrived at the remote Evans homestead and Wyn was forced to come to a crucial decision. Following the introduction of conscription his family was required to send one of their sons to join the Army. The 29-year old Wyn felt that he should enlist rather than his younger brother Robert; he enlisted at Blaenau Ffestiniog in January 1917.

Wyn is still fondly remembered for his poetry and in 1923, a bronze statue to the 'Shepherd Poet' was unveiled by his mother, in his home village in North Wales.

Above: Hedd Wyn’s statue - known as the Shepherd Poet in Trawsfynydd. (Photo – author).

The tragedy of Hedd Wyn underlined Wales’ losses during the war and the empty Eisteddfod chair was symbolic of empty chairs in homes throughout the country.

Today Wyn is buried in Artillery Wood Cemetery to the north of Ypres.

Above: Artillery Wood Cemetery. (Photo – CWGC) and Ellis Humphrey Evans’ headstone (Photo – IWM)

Above: A commemorative plaque near Artillery Wood Cemetery. (Photo – author)

Lying not far from his grave is another soldier poet. This is Francis Ledwidge, an Irishman born in the County Meath village of Slane. Remarkably Ledwidge was not only born in the same year as Wyn - 1887 - but was killed on the same day, just a short distance away. The two came from similar backgrounds and shared the same outlook on the war.

The son of a farm labourer, Ledwidge was forced to leave school at 13 to help support his widowed mother; he was already writing poetry which was first published in a newspaper when he was just 14 years old. Later he worked as a labourer, shop assistant and then in a local copper mine. He was a hard worker and a supporter of the labour movement.

In 1912, he sought advice from the well-known Dublin literary and social figure Lord Dunsany, and over the next few years received considerable assistance and support from this accomplished writer.

These were years of conflicting political loyalties and tensions in Ireland as the debate over Home Rule intensified; in his character and actions, Ledwidge highlighted many of these contradictions and divisions.

He was a nationalist and a member of the Irish Volunteers, set up to achieve Home Rule for Ireland. He profoundly disagreed with the views of Irish Parliamentary Party leader John Redmond who in September 1914, had urged the Volunteers to enlist in the British Army.

Nevertheless just a few days after Redmond’s speech, Ledwidge visited Richmond Barracks in Dublin and enlisted in Dunsany’s regiment, 5th Battalion Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, 10th Irish Division; his change of heart and his reasons for enlisting, have perplexed many students of his poetry ever since.

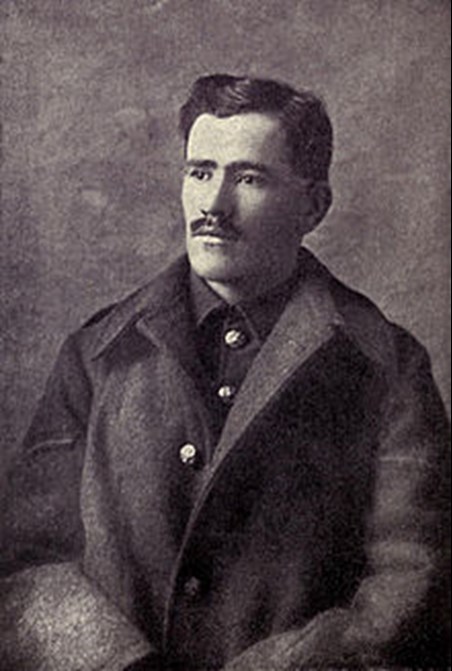

Above: Francis Ledwidge in uniform.

Ledwidge seems to have been a good soldier seeing service at Gallipoli - including Suvla Bay - and at Salonika, from where, following a bout of rheumatism, he was invalided to Cairo and eventually to Manchester. He was convalescing there when he heard of the Easter Rising in Dublin in April 1916.

The subsequent execution of the leaders’ of the Rising and particularly Ledwidge’s friend Thomas MacDonagh, gave rise to perhaps his best-known poem, lines of which are written on a memorial plaque near his grave at Artillery Wood:

“He shall not hear the bittern cry

In the wild sky where he is lain

Nor voices of the sweeter birds

Above the wailing of the rain”

Lament for Thomas MacDonagh

Above: Francis Ledwidge’s headstone in Artillery Wood Cemetery and the Memorial plaque near his grave. (Photos – author)

On the opening day of the battle, just a few miles from where Wyn was killed, Ledwidge and his comrades were taking tea during a break from laying a plank road, when a shell landed among them; five were killed including Ledwidge.

In his 1979 poem 'In Memorium, Francis Ledwidge', Seamus Heaney sums up Ledwidge’s character and contradictions, a farm-boy with little education who became a much-loved poet, a committed Irish nationalist who joined the British Army and a soldier who for three years suffered the horrors of war but never mentioned them in his poetry:

“In you, our dead enigma, all the strains

Criss-cross in useless equilibrium”

Ledwidge joined the Army voluntarily while Wyn was conscripted but otherwise, Heaney’s words could just as easily apply to that other enigmatic poet from the remote hills of North Wales.

Today Francis Ledwidge - known as the “Poet of the Blackbird” - and Hedd Wyn are commemorated by memorials near Artillery Wood cemetery and at their former homesteads but it is the survival of their poetry which remains their biggest contribution to the history and remembrance of the Great War.

Article by Jim Hamilton