The Even Shorter, Sadder Military Career of Thomas Beech

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Even Shorter, Sadder Military Career of Thomas Beech

Thomas Beech’s military service in the Great War lasted officially for thirty-five days. He attested on 5 January 1915 and killed himself on 1 February while home on leave.(1) He never served abroad.

Thomas was born on 25 January 1885 at 16 High Street, Burslem, the so-called Mother Town of the Staffordshire Potteries.(2) His mother, Emily (née Foster), registered the birth and signed the form with her mark. His father, Thomas, was described as a ‘collier’. (3) Thomas Jnr. was to be the fifth of eight children. The others were John Henry (b. 1875), William (b. 1877), Harry (b. 1881), James (b. 1883), Frederick (b. 1892), Leonard (b. 1895)(4), Sarah (b. 1896) and Eliza (b. 1899). Burslem was the quintessential industrial town and was overwhelmingly working-class in social composition.(5) All the family were employed either in mining or pottery making, mainly in low-skilled jobs. The ‘outlier’ was Harry, who joined the army as a Regular soldier in the North Staffordshire Regiment in 1899.

Above: A group of men of the 2nd Battalion of the North Staffordshire Regiment, pictured in India, 1907.

He served in South Africa and India, but was discharged -‘time expired’ - on 25 May 1911. By 1914 he was employed as a colliery labourer.

It is possible to trace the Beech family through the censuses of 1891, 1901 and 1911. They did not stray far from Thomas’s birth place. Throughout these years most of the family were living in New Street, a short, narrow, rather unprepossessing thoroughfare of two up and two down houses that ran between High Street and Market Place in the centre of the town.

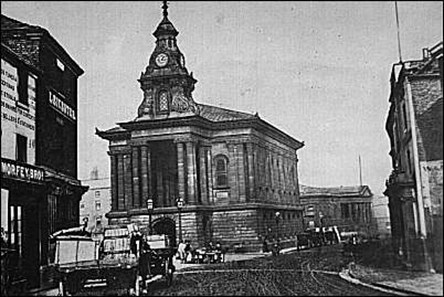

Above: Market Place, Burslem. Date unknown.

It was hemmed in by potbanks on both sides. (6)

Above: A Potbank (c. 1940)

The street was representative of Burslem’s older housing stock, which was in the process of being replaced during the two decades before the Great War. (7) The Beech family seemed to like it, though. They were living at No. 38 in 1891 and at No. 32 in 1901. The 1911 Census recorded Thomas’s widowed mother and four of her children living at No. 18, the eldest son John living at No. 8, James living at No. 39 and Thomas living at No. 25. (8)

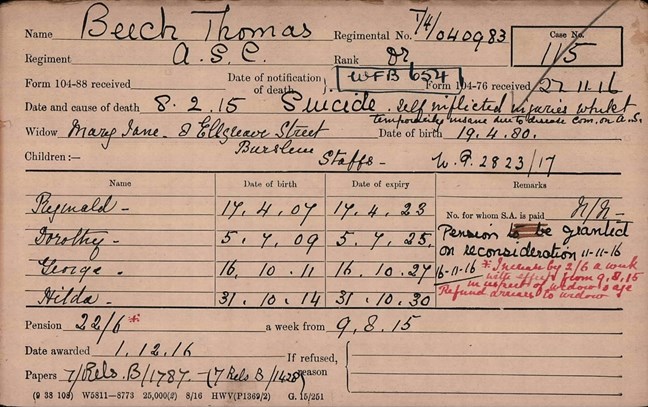

Beech volunteered for military service on 5 January 1915, attesting in Newcastle-under-Lyme. His attestation form gives his ‘apparent age’ as 29 years 6 months, (9) his height as 5 feet 5 ½ inches, his chest size (when fully expanded) as 38 ½ inches, his occupation as ‘waggoner’ and his address as 25 New Street, Burslem. (10) His marital status was noted and the names of his wife and four children were listed. Beech had married Mary Jane Hales, the eldest child of William Hales, a potter’s ovenman, at St Paul’s Church, Dalehall, on 16 December 1906.

Above: 'Oven Men' inside one of the area's potbanks.

Above: St Paul's Dale Hall (demolished 1974)

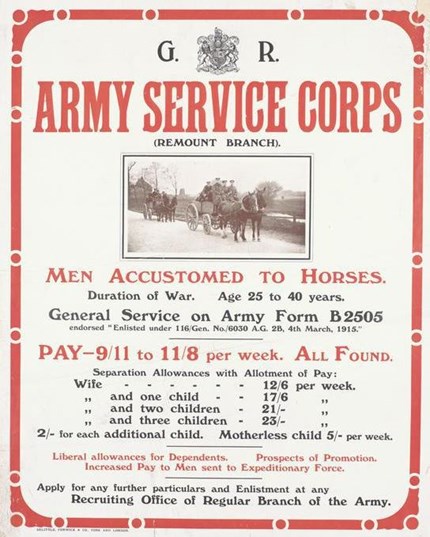

Their first child, Reginald, was born on 17 April 1907, and was followed by Dorothy (b. 5 July 1909). There would be two more children by the time Thomas volunteered, George (b. 16 October 1911) and Hilda (b. 31 October 1914).Beech joined the Army Service Corps [ASC] and was given the service number T4/040983. He was enlisted in No. 3 Coy ASC, a Depot Company for horsed transport based in Bradford, the following day.(11) He would have found his elder brother James already there.

James Beech, too, had volunteered for the ASC, the day before Thomas. His attestation form shows his ‘apparent age’ as 31 years 11 months, his height as 5 feet 3½ inches, his chest size (when fully expanded) as 36 inches, his occupation as ‘waggoner’, and his address as 39 New Street, Burslem. His marital status was noted and the names of his wife, Alice, and six children were listed. He was enlisted in No. 3 Coy ASC in Bradford on 5 January 1915.

Thomas’s enlistment meant that there were now three of the Beech brothers in uniform. The first to volunteer was almost certainly Harry. Although a former Regular, he was not a Reservist, but chose to re-enlist.(12) He became Acting Company Quartermaster Sergeant in my grandfather’s battalion, the 7th North Staffords, and was killed in action on the Gallipoli peninsula on 10 December 1915. He has no known grave.

Thomas Beech was not long in Bradford. According to the newspaper report of the inquest into his death, held in Burslem Town Hall on 10 February 1915, Mrs Beech testified that Thomas had been home on leave since 19 January and was due to report back on 2 February.(13)

Above: Burslem Town Hall (c. 1875)

On 1 February he announced that he was going for a walk, but never returned. At about 8 a.m. on 2 February a banksman at Sandbach Colliery in Cobridge, Frederick Crank, found a jacket attached to the cage at No. 2 Pit. (14) He discovered some cards in the jacket bearing the name of Thomas Beech. The name was familiar to Crank because this was the pit at which Thomas had worked as a waggoner. He reported the find to the colliery manager. When Mrs Beech confirmed that the jacket belonged to her husband, that he was wearing it when he left home and that he was missing, the police were notified.

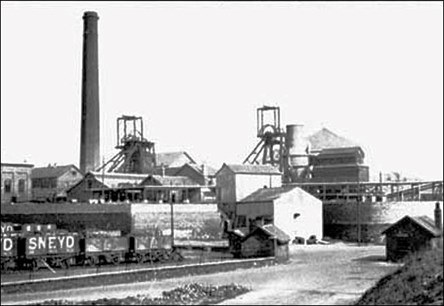

Above: Sneyd colliery although not the colliery where Thomas worked, was located between Burslem and Smallthorne.

It was not possible to mount a search of the shaft until the following Monday, 8 February. Pit Shaft No. 2 had been flooded and was not in use. The pit mouth had accordingly been fenced off. William Hutton, colliery engineer, William Mordy, the mine manager, and Joseph Garner, fireman, accompanied by P.C. Ernest Hill, descended the 780 feet deep shaft and managed, with great difficulty in fume-filled and fetid air and with water pouring on them, to recover the body from the sump.(15) The verdict of the Inquest was ‘Suicide while temporarily of unsound mind’.

My old tutor, the Rev. Professor John McManners, was fond of describing historians as ‘why people’. There were two aspects to this: the first was asking ‘why’; the second was answering ‘why’. I’ve never had problems with the first ‘why’. Curiosity is the sovereign requirement of a historian, though I am forever appalled by my lack of it. It is answering ‘why’ that gives me problems. Of course, we have to try and find answers, but where I differed from Jack McManners was in my belief that answers could not always be found, which Jack called ‘a counsel of despair’. Where Thomas Beech is concerned, a counsel of despair is all I really have to offer.

The list of whys is considerable. Why did a thirty year old, employed, married man with four children, the youngest of whom was less than three months’ old, volunteer for military service when he was seemingly not in good health? Why did he volunteer in Newcastle-under-Lyme, four miles from his house, when Burslem’s recruiting office was a matter of yards away? Why did he kill himself? Why did he kill himself where he did and in such a desperate and unusual manner? To try and answer these questions is to enter the world of conjecture.

Historians have long speculated about what led men such as Thomas Beech to volunteer. His decision was hardly unique. His brother James had even more children than he did, as did my own maternal grandfather. We can all make lists of ‘factors’ - an escape from boredom or unemployment, bravado, peer pressure, patriotism - but which of these, if any, applied in individual cases is often beyond knowing. I sometimes wonder whether the men themselves always had a clear understanding of their motivation.

Above: Recruits (IWM Q 30071)

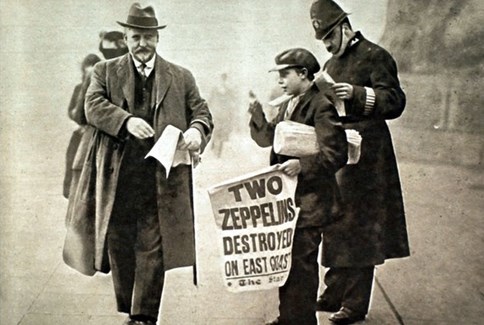

Some aspects of Beech’s recruitment stand out, however. The first is the timing. He did not rush to the colours during the first flush of ‘war enthusiasm’.

The war had not been over by Christmas. At least twenty-three Burslem men had been killed by the end of 1914, a number that would have been multiplied across the other Potteries towns and the mining villages of North Staffordshire. The local newspaper’s coverage of the war was detailed and spared no one’s feelings.

Beech could have been in little doubt about the realities of war. Christmas and the turn of the year are times for reflection. Perhaps he and his brother had made a resolution to ‘do their bit’ in the New Year, a decision already made by their elder brother Harry. Their apparent choice of the Army Service Corps, suitable to men of their age and work experience, also implies that they had thought the decision through.

The second is his attestation in Newcastle-under-Lyme. My initial interpretation of this was that he was somehow attempting to volunteer in ‘secret’, further away from home. But this was before I discovered that his brother had attested there the day before. James Beech had attempted to join the army on 29 December 1914, but was rejected. He had admitted to the examining physician, Dr Gilchrist, that he had ‘always suffered from shortness of breath when “bustled”’. Gilchrist made Beech ‘hurry across the room’ and then failed him.(16) James’s attestation in Newcastle-under-Lyme, on 4 January 1915, was therefore his second attempt to join up.

This time he was successful. Presumably, he now knew to keep quiet about his ‘breathlessness’ and was passed after the doctor there made ‘a very cursory examination’. (The change to a different recruitment office was a familiar tactic during the period of voluntary recruitment.) But this does not explain why Thomas had to attest in Newcastle when he could just have walked over the road from his house. Perhaps he, too, felt he had medical issues that would have got him rejected in Burslem by the conscientious Dr Gilchrist, but if James could pass muster in Newcastle, then so could he. If so, this may throw light on his eventual suicide.

Suicide is not only the most personal of acts, but also a social phenomenon. As a personal act it has been extensively studied by psychiatrists and psychologists. As a social phenomenon it played an important role in the birth of sociology as a discipline.(17) Suicide has what might be termed ‘internal causes’, involving mental health and the biochemistry of the brain, resulting in depression and feelings of failure and inadequacy, and ‘external causes’, such as poverty, homelessness, long term illness, pain, loneliness, bereavement, rejection, and other possible traumas, such as military combat. It is difficult to situate Thomas Beech confidently within this range of explanations. He was not unemployed. He had not suffered a bereavement. He was not obviously lonely, but part of a close-knit family and working-class community. His marriage appears to have been solid, as far as it is possible to tell. He was not homeless or suffering from poverty. He had not experienced ‘war trauma’. Even in adjusting to a new life in the army, he had his brother with him.

The closest thing to an explanation of Thomas Beech’s act was his wife’s statement to the Inquest that her husband had been ill and that this worried him ‘a lot’. She testified that her husband ‘said he was tired of his suffering and it would drive him mad [my emphasis]’, but he had never threatened to injure himself.(18) There was no indication of what illness Thomas was suffering from or thought he was suffering from. His Commanding Officer confirmed that ‘no information as to [Beech’s] illness was forthcoming’ and that he had never complained of being ill while with his unit.

Some things about Thomas Beech’s suicide stand out, however, if not their meaning. He killed himself the day before he was due to return to the army. Was this fear of the army and the war or was he worried that his illness would lead to his failure as a soldier, as would be the case with his brother?(19) Burslem was not short of places where suicide could be achieved - canals, railway lines, bridges, kilns - not to mention easy access to knives, rope, gas and poisons. Yet he killed himself at his former place of work. This is surely significant, but significant of what is unfathomable. The fact that he left his jacket at the pithead suggests a wish for his body to be found and, in the words of Lev Wood, ‘it is like an unsigned suicide note and represents a statement of intent’. When that intent was formed, however, is unclear. Did he ‘go for a walk’ with the intention of killing himself?

Above: A pithead shaft, was this similar to the one Thomas visited on his final day?

As Peter Hodgkinson points out, ‘suicide can be impulsive as well as planned and like murder is often seen by the individual as the “only solution” to whatever the issue is’. It is possible that Beech left home with no suicidal intent, but with a head full of negative thoughts that eventually overwhelmed him. Who can tell? The method he chose, however, certainly required determination on his part. This impressed at least one member of the Inquest jury, who was reported as saying ‘the pit-mouth was fenced and anyone would have to go out of his way to get there’. Whenever and why Thomas Beech made the decision to kill himself, his final act was purposeful, determined and guaranteed to be fatal. This was no ‘cry for help’.

Beech’s suicide left his family in a precarious financial position, without his army pay and without a war widow’s pension. On 2 September 1915 the Assistant Financial Secretary at the War Office wrote to the officer in charge of Army Service Corps Records, Woolwich, as follows: ‘I am directed to inform you that in view of the circumstances of the death of No. T4/040983 Driver Thomas Beech, Army Service Corps, his widow and children are not eligible for pension from Army Funds. Mrs Beech and the Regimental Paymaster should be informed accordingly’. A more humane decision was later made, after ‘reconsideration’, though not until 11 November 1916, when Mrs Beech was awarded a pension of 22s 6d a week, with arrears backdated to 9 August 1915. (20)

What the family lived on until then is anyone’s guess. Mary Jane never remarried. By 1921 she was supporting her family by working as a teapot fettler at Cooper & Co. in Longport. She seems to have lived most of the rest of her life with her youngest child, Hilda. She died in 1957, aged 77.

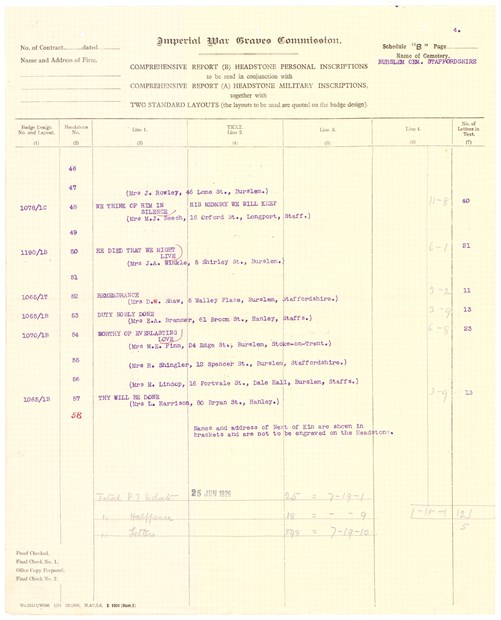

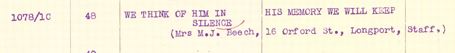

Thomas Beech has a Commonwealth War Graves headstone in Burslem cemetery. It contains the personal inscription:

WE THINK OF HIM IN SILENCE

HIS MEMORY WE WILL KEEP

Above and Below (enlarged): The entry on the IWGC (as it was then) 'Comprehensive Report' for Burslem Cemetery

The inscription was expensive, costing 11s 8d, almost twice as much as the next most expensive inscription listed on the same page. (21) It is not a conventional sentiment. The word ‘silence’ resonates with the hurt and stigma attached to his suicide. In the words of Edwin Shneidman,‘the person who commits suicide leaves his psychological skeleton in the survivor’s emotional closet’. (22) When a man kills himself during a great war, it is tempting to attribute causation to the war, but it is difficult to explain Thomas Beech’s suicide as ‘war related’. After all, people kill themselves all the time and, according to most studies, they did so rather less frequently than normal during the two world wars. Ultimately, no satisfactory explanation for his act is possible. He took his reasons with him as he plunged into the darkness leaving his family to live with the legacy.

Dr John Bourne

John Bourne taught History at Birmingham University for thirty years before his retirement in September 2009. He founded the Centre for First World War Studies, of which he was Director from 2002 to 2009, as well as the MA in British First World War Studies. He has written widely on the British experience of the Great War on the war front and the home front. He is currently completing a multi-biography of Britain’s Western Front Generals. He is a Vice President of The Western Front Association, a Member of the British Commission for Military History, a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and Hon. Professor of First World War Studies at the University of Wolverhampton.

Notes

(1). His service actually lasted 28 days. The army’s calculation of his service was based on a date of death of 8 February 1915. This was the date his body was recovered. He almost certainly died on 1 February. The time he spent with his unit was probably no more than 14 days.

(2). ‘High Street’ immediately conjures up images of a major thoroughfare, with bustling commercial activity. Burslem’s High Street may once have been like this, but by 1885 it was something of a backwater of terraced houses and potbanks.

(3). The area was mined for coal and ironstone. The term ‘collier’ was confined to miners of coal. Thomas Beech was a ‘loader’, a man who shovelled coal into tubs for transport to the pit bottom and, ultimately, the surface. By the time of the 1901 Census, Beech’s employment had declined somewhat to that of ‘bricklayer’s labourer’.

(4). Leonard Beech died in 1907, aged 13, as a result of ‘mitral regurgitation’, a fault with the heart’s mitral valve that allows blood to flow back into the heart, perhaps better known now as a ‘leaky valve’.

(5). For a portrait of Burslem on the eve of the Great War, see John Bourne, ‘Burslem and its Roll of Honour 1914—1918’, Midland History, 39 (2) (Autumn 2014), pp. 206-11

(6). At one time, New Street boasted two pubs, ‘The Turk’s Head Inn’ and the ‘New Crown Inn’. Neither seems to have survived to the eve of the Great War, but local drinkers still had plenty of choice. In 1907 there were 42 pubs and 102 beer houses in Burslem, famously described by the painter, poet and raconteur Arthur Berry as ‘the finest drinking town in England’.

(7). Much of this newer housing, especially that in the Jenkins and on the Park Estate, still stands.

(8). Thomas Beech Snr died from his injuries on 27 December 1914 after a fall downstairs on Christmas Day. He had eaten a Christmas Lunch at Thomas Jnr’s house. Thomas brought his father back home at about 3.30 p.m. and put him to bed (which rather suggests he was the worse for wear). Four hours later, his niece Eliza heard a bang and found Thomas Snr at the foot of the stairs. He was reported as having said that he ‘must have got up in his sleep and fallen down the stairs’. The Inquest recorded a verdict of ‘accidental death’.I owe this information to Su Handford.

(9). ‘Apparent age’ is the form of words used on Army Form B. 2505. This was not a world where proof of age was easily produced and in which birth certificates were not required. Beech’s actual age was 20 days short of his 30th birthday.

(10). Waggoner was the term for the man who brought empty coal tubs to the coal face and took loaded tubs back to the pit bottom.

(11). As a waggoner, Beech would have been familiar with horses. He had also worked as a carter in the past.

(12). Harry’s service file for the Great War has not survived, so the date of his re-enlistment is unknown, but his service number, 8741, suggests an August 1914 enlistment. He was with the battalion at the time of its entry into a theatre of war, 2 July 1915.

(13). The inquest was reported in the Staffordshire Sentinel on 11 February 1915

(14). A banksman worked at the pithead to organise the loading or unloading of the cages. He would have been familiar with the miners who worked below ground. Burslem had a plethora of small pits, but most of these had ceased to function in the 1880s as a result of flooding, leaving a few bigger,deeper pits, Sneyd, Grange and Racecourse, within the boundaries of the former borough. Sandbach Colliery was slightly odd. ‘It had been opened by 1856 but seems to have been closed temporarily during the last decade of the century.By 1902 it had 41 employees below ground and 17 above, but, though still in operation during the First World War, it had been closed by the early 1920's.’ See https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/staffs/vol8/pp125-142 especially footnote 338. Sandbach Colliery is shown on the 1877 OS map of Burslem, but not the 1898 map or the 1926 map.

(15). The Coroner’s Jury were impressed with the ‘pluck’ of P.C. Hill, who – unlike the others – was unfamiliar with mining and mining conditions. Hill was commended by the Watch Committee for his bravery. He joined the army later in 1915, serving with distinction in the 1/5th Battalion South Staffordshire Regiment, 46th (North Midland) Division TF, being wounded twice and gassed three times. He returned to the Stoke-on-Trent City Police after the war and reached the rank of sergeant. He died in November 1930, aged only 42. He is buried in Burslem Cemetery. I should like to thank Su Handford for bringing the war services of P.C. Hill to my attention.

(16). Dr Adam Gilchrist’s practice was in Bleak Street, Burslem.He was a graduate of the University of Aberdeen (1908), and a Scot like many of Burslem’s doctors, then and later (when they weren’t Irish).

(17). I cut my sociological teeth as a first year undergraduate by sneaking into the lectures of the immortal Sid Holloway at Leicester University as he stuttered his way through the ideas of Emile Durkheim, the ‘father of sociology’, and his classic work Le Suicide (1897). I was profoundly impressed by Mr Holloway, but less impressed with Professor Durkheim’s analysis of suicide rates in Catholic and Protestant countries. For a survey of the changing nature of suicide over time in modern England and Wales, see Kyla Thomas& D. Gunnell, ‘Suicide in England and Wales, 1861-2007: A Time Trend Analysis’, InternationalJournal of Epidemiology (December 2010). I owe this reference to Nick Baker.

(18). I think there is an implication in Mrs Beech’s reported words to the Inquest that her husband’s ill health was of longstanding and not something that had just developed. I may be misinterpreting this.

(19). Dr Gilchrist’s rejection of James Beech was medically prescient. James’s military service was almost as short-lived as that of his brother. He was discharged on 8 June 1915 ‘as being unlikely to make an efficient soldier’ on grounds of ill health. Beech’s illness was Valvular Disease of the Heart [VDH], a problem that had arisen in childhood. Since joining the army he had ‘been continually attending sick parade’ and was eventually hospitalised in Shoreham, Sussex. He died in Stoke-on-Trent in 1941, aged 58.

(20). The issue of Mrs Beech’s pension is worthy of an article all to itself, but there are people more able to write it than me. For a discussion of the problems posed to families and to the authorities by the suicide of serving soldiers, see Andrea Hetherington, British Widows of the First World War: The Forgotten Legion (Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military, 2018), pp. 83-89.For a discussion of how pension claims were reconsidered, see Craig Suddick’s WFA article: Using the RFC to unlock the workings of widow’s pensions

The ‘humane’ outcome for Mrs Beech and her family was probably the result of a legal nicety. Nick Baker points out that the Inquest jury’s verdict that the balance of his mind was ‘temporarily disturbed,’ combined withthe lack of diagnosed insanity upon acceptance into the army, meant that Beech must havebecome temporally insane (legally anyway) between being medically examined and committing suicide, thus ‘while in service’, as stated on the Pension Card.

(21). Personal inscriptions were charged at the rate of 3 ½ pence per letter, a cost that was a deterrent to many working class families. This led to accusations of hypocrisy against the (then) Imperial War Graves Commission, as the expense appeared to run counter to the Commission’s stated intention that remembrance should reflect ‘equality of sacrifice’.

(22). Edwin S. Shneidman (1918-2009), clinical psychologist, known as the ‘father of suicide research’. I owe this reference to Dr Peter Hodgkinson.

Acknowledgements

My special thanks to Mick Rowson for drawing Thomas Beech’s history to my attention. I am also indebted to Nick Baker, Dr Angela Gaffney, Su Handford, Dr Peter Hodgkinson, Andy Johnson, Dr Geoffrey Noon, Craig Suddick and Lev Wood for help with the research and to Nick Baker, Andy Johnson, Lev Wood and Professor Peter Simkins for their comments on a draft.