The Kaiser's Battle by Martin Middlebrook - how accurate are the statistics?

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Kaiser's Battle by Martin Middlebrook - how accurate are the statistics?

I am sure that many members of The Western Front Association were introduced to the subject of the Great War by reading Martin Middlebrook's The First Day on the Somme, which was first published 53 years after the end of the war in 1971. It is sobering to realise that nearly as many years have elapsed since its original publication to the recent anniversary of the end of the war.

Notwithstanding this book's appeal (it has sold over 150,000 copies) Martin has stated on numerous occasions that he feels that his second book on the Somme, The Kaiser's Battle, which describes the first day of the German Spring offensive on 21 March 1918 to be a better researched, better written and more important historically than his earlier book on the first day of the 1916 battle. Despite this, 'First Day' outsells 'The Kaiser's Battle' by a substantial margin.

Martin Middlebrook giving his 'cemeteries and headstones' talk to attentive members of The WFA.

In The Kaiser's Battle, which was first published by Allen Lane in 1978, Martin analyses the first day of the German Spring Offensive ('Operation Michael') which commenced on 21 March 1918. Using numerous quotations from both British and German soldiers, he provides a narrative of the German attack on the Third and Fifth Armies, and also looked to analyse the casualties, including the fatal casualties suffered by British units. This research took place before today's technology was available. The fatal casualties that Martin detailed obviously could not be extracted digitally either from 'Soldiers Died in the Great War' (which was then only available as a series of books representing the regiments of the British Army), or from the yet-to-be-conceived Commonwealth War Graves Commission website. Instead Martin had to borrow from the CWGC registers for over 160 cemeteries as well as the registers for the two memorials for the missing that commemorate those with no known grave who faced the Germans on that March day one hundred years ago.(1) Not only did he count the dead of that day, a laborious task in itself, but he also noted the units the men belonged to, battalion by battalion. It is incredible to consider the man-hours that Martin put into this exercise, and how potentially prone to errors this approach could be.

The question arises whether an approach extracting the data digitally from the CWGC's website and the manipulation of such data will produce substantially different figures to those provided in The Kaiser's Battle. It is therefore pertinent to re-examine the data to see if radically different numbers are obtained, or if the manual data extraction undertaken by Martin so laboriously in the mid-1970s remains valid.

For this article, data was extracted from the CWGC web site in January 2018,(2) the data obtained listing all men killed on 21 March 1918 who are buried or commemorated in France.

Another reason for undertaking a new analysis of the casualties on 21 March 1918 is the fact that Martin's analysis looked purely at infantry and pioneer battalion fatalities, and did not take account of other divisional assets such as Royal Engineer Field Companies, Trench Mortar Batteries, RAMC Field Ambulances and men from the Machine Gun Corps.(3) Similarly Royal Field Artillery Brigades (many of which were divisional units) were not incorporated into Martin's original analysis. These have now been taken into consideration.(4)

Royal Garrison Artillery, Royal Flying Corps and Tank Corps fatalities are not included in the following analysis, nor are Labour Corps and Entrenching battalion fatalities.(5)

Problems with the data

Even with the ability to obtain downloads from the CWGC web site there remains problems with the data. Numerous battalions detailed by the CWGC are known not to have been in existence on 21 March - mainly due to the merger of many battalions in the first weeks of 1918.(6) It is also the case that a number of officers were detailed as being with their 'parent' regiment, despite being attached to other regiments.(7) Among other issues the analysis has highlighted is that there are a number of men listed by the CWGC who were killed at an uncertain date between 21 March and a later date.(8)

The analysis of fatalities of the 21 March only tell a fraction of the full story. Many men were wounded, with no doubt hundreds of these men succumbing to their injuries on subsequent dates. This includes many men who were gassed.

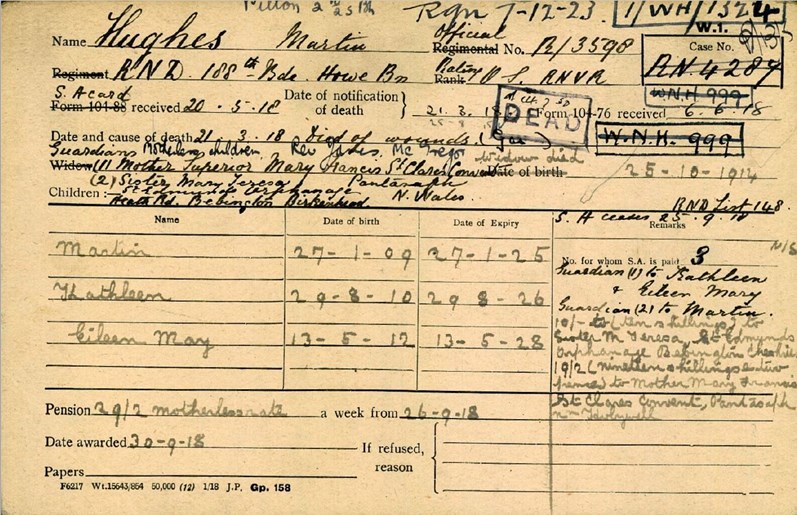

Able Seaman Martin Hughes, Howe Bttn, RND who died of wounds (gas) on 21 March 1918. This image is from the WFA's Pension Record Cards; this archive is available via The WFA's web site

It would normally be possible to extract some data from unit war diaries for men who were wounded, but this is almost impossible for this day's action because a high proportion of the war diaries were not written up or have only scanty entries for the day's action.

The other problem with this approach is that of prisoners taken by the Germans. The attack on 21 March netted a massive haul of prisoners for the Germans. These men who were captured were also casualties and (unlike those whose wounds could be patched up) a permanent loss to the British Army. It is outside the scope of this article to re-analyse the number of prisoners taken by the Germans; Martin suggested these could be in the region of 21,000, with possibly 10,000 men being wounded. It is certain that no truly accurate figure will ever be known.

Summary of the attack; strategy and tactics

It is probably worthwhile briefly summarising the extent of the German attack on 21 March. It was made on a front of 50 miles (compared to the 16 mile front attacked by the BEF on 1 July 1916) and against a large part of the Third Army (under General Sir Julian Byng). The Third Army held the line from the region of Arras to the Flesquières Salient, although this salient was not intended to be taken on 21 March, leaving it to be 'pinched out' with attacks on the flanks.

To the south, the Germans would attack virtually the whole of the Fifth Army (General Sir Hubert Gough). The Fifth Army was hampered by having been instructed to take over from the French a stretch of line at the extreme right of the British line, which now extended five miles south of the River Oise. The defences taken over from the French on this newly acquired front line were in a poor state of repair and much work would have been needed - which was not possible in the time available prior to the attack - to bring it up to an acceptable standard.

British lines of communication and proximity to the channel ports meant that as the line ran from the Ypres salient in the north towards the newly acquired trenches in the south, the less concern there was at GHQ about a potential loss of ground. Gough was aware of the relative weakness of his Army and the fact that ground lost in this area was far less important to the overall position than ground lost in the north. In 'Fifth Army', apparently written by Hubert Gough, but actually ghost-written by Bernard Newman, Gough says the following:

Haig was absolutely sound in his judgement to keep his reserves in the north and to leave the Fifth Army to do the best it could with its divisions to hold up and perhaps exhaust the German forces....in my discussion with Haig it was clearly understood by both of us that the role I was to play was to retire gradually...without exposing my Army to annihilation. (9)

The Fifth Army was reinforced by the 18th (Eastern), 20th and 66th (East Lancashire) Divisions in February, but despite this, Gough had fewer troops per mile of front than in the Second Army around Ypres. (10)

The evolution of tactics during the course of the war had, by the Spring of 1918 meant that the 'front line' was no longer as strong as it had been earlier in the war. Instead, the defence relied on a thinly manned forward zone which would offer a limited degree of resistance to any German attack, this was intended to disrupt rather than halt any advance. The main resistance would be provided in a deep 'battle zone' which would be augmented by strong points and redoubts - these would offer interconnecting fields of fire which would break up German attacks - or so the theory went. The effectiveness of these strong points and redoubts was highly dependent on the defenders being able to clearly observe the ground they were supposed to be defending. This was to be a major issue when Operation Michael was launched against the Third and Fifth Armies when the 'strong points' were left stranded in thick fog on the morning of the battle and were unable to dominate the ground between them.

Royal Field Artillery positions were generally within the Battle Zone, although a small number were deployed in an anti-tank role in the Forward Zone. RFA officers and signallers were positioned forward to enable the guns to be ranged onto attacking troops, but the gunners of the RFA deployed deep in the Battle Zone would not have expected to have been overrun by any attack.

Two of the 21 A7V Sturmpanzer-Kraftwagen fielded by Germany in March 1918 pause on a dirt road for a photo opportunity. Mingled amongst the lead tank's 18 man crew are a number of French prisoners of war. Image courtesy of 'drakegoodman' via flickr.

Deployment of Divisions

On the eve of the German attack, the Third and Fifth Armies had the following infantry divisions (listed north to south) in the line:

Third Army: This needs to be looked at in three sectors. Firstly, in the north the 4th, 15th (Scottish) and 3rd Divisions were in the vicinity of Arras and not subject to the German attack.

In the centre, the 34th, 59th (North Midland), 6th and 51st (Highland) Divisions were heavily involved on 21 March.

In the south of the Third Army's front were the 17th (Northern), 63rd (RND) and 47th (London) Divisions. These three Divisions were holding the Flesquières Salient which was not an objective of the German attack.

Fifth Army: North to south were deployed the 9th (Scottish), 21st, 16th (Irish), 66th (East Lancashire), 24th, 61st (South Midland), 30th, 36th (Ulster), 14th (Light) , 18th (Eastern) and 58th (London) Divisions.

Therefore, any comparison of the casualties taken by the two British Armies involved needs to take account of the fact that eleven of Fifth Army's divisions were attacked, but only four belonging to Third Army were heavily involved.

Due to the Germans successfully mounting an effective deception operation to cover where the attack would take place, it was only in the hours leading up to the assault that accurate intelligence of the location became known. This came too late for any real changes to be made to prepare for the forthcoming assault, although it seems that a number of artillery batteries were moved once it became known that a German attack was about to take place. The fact that these batteries moved position, and other batteries were undetected by the Germans prior to the attack no doubt saved these guns from receiving the attention from German artillery. Despite this, a significant number of RFA and RGA gunners became fatalities during the course of the German attack on 21 March. The 6th Division lost the greatest number of RFA fatalities of those divisions involved on this day, its 2nd and 24 Brigades RFA losing a combined five officers and 37 other ranks killed.

Through his interviews and questioning of participants there is evidence of two artillery batteries either firing 'over open sights' on the advancing Germans or men of the RFA defending their guns with rifles. It is likely that these incidents were rare, and the fatalities incurred in such last ditch fighting would form only a fraction of artillery casualties, most of which would have been incurred by German counter-battery fire either by High Explosive shelling or gas-shelling.(11)

Royal Garrison Artillery batteries were also targeted by the Germans. These were not divisional assets, but Corps or Army units and do not therefore form part of the divisional totals discussed below. However, it should be noted that total RGA fatalities on the day numbered over 200.(12) Some of the fatalities among RGA units would, like the RFA, have been to officers and men manning forward observation posts.

The Royal Engineer fatalities on this day are also worth mentioning. Eleven officers and 139 other ranks from the Royal Engineers were killed. The majority of these were from Field Companies attached to divisions in the Third and Fifth Armies, but the remainder were from a wide variety of other units.(13) The greatest number of fatalities to Field Companies of Royal Engineers was again in 6th Division, whose 12th, 459th and 509th Field Companies plus the division's RE signallers lost three officers and 26 men between them. Martin Middlebrook includes an account of one sapper from a Field Company (478th, part of 61st Division) becoming involved in the fighting on 21 March.(14)

Other divisional troops became fatalities, but these are small in number: Trench Mortar Battery deaths are possibly around 40.(15) Field Ambulance deaths total around 60, but this excludes Medical Officers attached to fighting units.(16)

Analysis shows that around 93 percent of the divisional fatalities in Third and Fifth Armies on 21 March were from infantry or MGC units. Most of the remainder (4.5%) being RFA fatalities (including those from Medium TMB and Divisional Artillery Columns).

A German transport column moving forward along the Albert-Bapaume road, March 1918. © IWM (Q 60474)

There is not space within this article to give a blow by blow account of the fighting but one action is perhaps more famous than many others, that of the defence of Manchester Hill by Lt Col Elstob and 'D' Company of the 16th Manchesters. It can be used to look at the casualty figures provided by the unit's war diary as well as that supplied by Martin Middlebrook in The Kaiser's Battle. The position ('Manchester Redoubt' according to the war diary) was defended by around eight officers and 160 men of the 16th Battalion. It should be noted that only one company of the battalion was defending Manchester Hill, but the fatalities quoted below are for the entire battalion.

The battalion's war diary in a report dated 1st April 1918 gives casualties from 21 March to 25 March as: Officers 5 wounded and 18 missing; Other Ranks 8 wounded and 593 missing. Clearly the war diary is ignorant of, or unable to put a number to the fatalities incurred.(17)

Martin counted 73 men of the battalion killed on 21 March, but the modern downloaded data from the CWGC web site show four officers and 77 men killed on this day. (Another 6 men being recorded by the CWGC between the 22nd and 25th March - these may have been fatal wounds from the fighting but are ignored for the purpose of this analysis). From this we can conclude Martin's data for the battalion is reasonably accurate, but we cannot extract much from the war diary entry, written by a 2nd Lieutenant commanding the battalion, other than to assume most of the 'missing' became prisoners.

Comparison

How does the total divisional fatalities for 21 March compare to Martin Middlebrook's research?

Martin lists the fatalities per division in the following decreasing order, with a modern extraction of the data (infantry and pioneers) being provided in the adjoining column. The third column adds other divisional assets (RFA, RE, RAMC, MGC) to the infantry and pioneer fatalities.

| Div | Middlebrook | "New" | New - total div assets | notes |

| 59 | 807 | 825 | 906 | |

| 66 | 711 | 756 | 791 | |

| 6 | 602 | 606 | 714 | |

| 16 | 572 | 650* | 721* | *includes 56 men of 1/RDF who were killed 21 March onwards see FN 8 |

| 14 | 370 | 419 | 478 | |

| 61 | 361 | 414* | 462* | *includes 36 men of 5/Gordon Highlanders who were killed 21 March onwards see FN 8 |

| 51 | 309 | 318 | 394 | |

| 21 | 305 | 299 | 349 | |

| 24 | 276 | 291 | 334 | |

| 36 | 267 | 279 | 334 | |

| 30 | 245 | 258 | 312 | |

| 18 | 182 | 191 | 241 | |

| 34 | n/a | 220 | 261 | |

| 58 | n/a | 188 | 201 | front not all attacked - extended south of the Michael attack |

| 47 | n/a | 112 | 124 | Flesquières |

| 9 | n/a | 93 | 116 | although not in the Flesquières salient, part of front of the division was adjoining the salient and therefore did not suffer an attack across all its positions |

| 17 | n/a | 77 | 87 | Flesquières |

| 63 | n/a | 22 | 27 | Flesquières |

As can be seen, the totals per division that Martin listed are very close to those extracted by the recent analysis, but are generally understated by a small amount. The three divisions which have the greatest difference being the 16th, 14th and 61st. (18)

It may be helpful to re-order these divisions from North to South which will set these figures into the context of the attack on 21 March.

| Division | Inf & | RFA (including | MGC | RE | RAMC | Total | Notes | |

| Pioneer | TMB, DAC) | |||||||

| 34 | 220 | 15 | 22 | 1 | 3 | 261 | partly attacked | Third Army |

| 59 | 825 | 27 | 39 | 6 | 9 | 906 | " | |

| 6 | 606 | 49 | 21 | 29 | 9 | 714 | " | |

| 51 | 318 | 18 | 42 | 9 | 7 | 394 | " | |

| 17 | 77 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 87 | Flesquières | " |

| RND | 22 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 27 | Flesquières | " |

| 47 | 112 | 1 | 2 | 9 | 0 | 124 | Flesquières | " |

| 9 | 93 | 15 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 116 | partly attacked | Fifth Army |

| 21 | 299 | 15 | 32 | 1 | 2 | 349 | " | |

| 16 | 650 | 21 | 40 | 5 | 5 | 721 | " | |

| 66 | 756 | 23 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 791 | " | |

| 24 | 291 | 8 | 29 | 6 | 0 | 334 | " | |

| 61 | 414 | 9 | 33 | 4 | 2 | 462 | " | |

| 30 | 258 | 11 | 29 | 12 | 2 | 312 | " | |

| 36 | 279 | 25 | 27 | 2 | 1 | 334 | " | |

| 14 | 419 | 19 | 29 | 6 | 5 | 478 | " | |

| 18 | 191 | 30 | 19 | 1 | 0 | 241 | " | |

| 58 | 188 | 5 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 201 | partly attacked | " |

Finally, a brief look at the battalions with most fatalities would be helpful. Martin lists seven battalions with in excess of 100 men killed, however this seems to actually be eleven battalions.

Clustering these into the Divisions and infantry brigades may help highlight the most intensive fighting.

| Officers | Other Ranks | Middlebrook | |

| 59th Div, 176 Brigade | |||

| 5th North Staffs | 9 | 93 | n/a |

| 2/6th North Staffs | 3 | 107 | n/a |

| 2/6th South Staffs | 3 | 103 | 112 |

| 59th Div, 178 Brigade | |||

| 2/5th Sher For | 4 | 104 | 109 |

| 2/6th Sher For | 9 | 124 | 131 |

| 7th Sher For | 11 | 164 | 171 |

| 6th Div, 18 Brigade | |||

| 1st West Yorks | 3 | 103 | 107 |

| 2nd DLI | 7 | 114 | 122 |

| 16th Div, 48 Brigade | |||

| 1 RDF | 4 | 112 | n/a |

| 2 RDF | 5 | 108 | 108 |

| 66th Div, 198 Brigade | |||

| 4th East Lancs | 7 | 100 | n/a |

Third Army fatalities were , excluding the losses to the three divisions facing the Flesquières salient, in absolute terms in the order of 2,275 (34% of the total). What should be noted is that (again disregarding the Flesquières position) there were only four divisions attacked on the Third Army front and one of these four divisions (the 34th) was only partly involved - with just one brigade of the 34th actually being attacked.

The Fifth Army had nine divisions whose front line positions were fully attacked. In addition the 9th Division (adjoining the southern portion of the Flesquières salient) and the 58th Division (whose front extended a short distance south of the attack) were also attacked, but only on part of their respective frontages. The Fifth Army incurred some 4,339 fatalities on the day (66% of the total).

Memorials on the ground

Other than the immaculate cemeteries and Memorials to the Missing (Third Army at Arras, Fifth Army at Pozières) there are no memorials on the ground to what happened on 21 March 1918, with a single exception.

Just outside Hargicourt, there stands a memorial to the commanding officer of the 4th East Lancs, Lt-Col Arthur Wrenford who was killed on 21 March 1918.

, near Hargicourt (author's collection)

, near Hargicourt (author's collection)

The 4th East Lancs had three companies in the line and one in support and stood their ground, resisting strenuously until they were outflanked and attacked from the rear. Almost every officer and man became a casualty or was captured and although the War Diary reported Wrenford "wounded and taken prisoner", in fact he was killed. His body could not be found so his mother erected a stone cross with a surround of stone posts and railings inscribed in French on one side and English on the other. (19)

The French inscription on Wrenford's memorial (author's collection)

Conclusion

The Kaiser's Battle by Martin Middlebrook remains the definitive account of one of the most important day's fighting in the Great War. The true losses in terms of killed, wounded and prisoners will never be known, but it is without doubt the British Army suffered grievously at the hands of the Germans.

Although the Third Army incurred the smaller percentage of the total fatalities, of the eleven battalions which took more than 100 fatalities, eight were in the Third Army area, with 'only' three in the Fifth Army area. This does not mean that there was any difference in the fighting ability of the units, but it may point to units in the Fifth Army having an understanding of Gough's willingness to give ground in the south. This, however, is a risky assessment as such high-level perceptions will not have had much bearing on the ground in the face of overwhelming artillery bombardment with German troops infiltrating and bypassing strong points. This conclusion, however, is supported by an analysis of the 'average losses per division'.

The four divisions of the Third Army that were frontally attacked (i.e. excluding those manning the Flesquières Salient) lost, as fatalities, on average 569 men each. The eleven divisions of the Fifth Army that were attacked (and this includes the 9th and 58th, although neither of these were fully engaged across all their frontage) each lost on average 394 men as fatalities. 'Averages' and statistics can of course lead to misleading conclusions, but it would seem on the face of this data that Gough's units were more willing to trade ground than those in the Third Army. Which should not come as a surprise in view of Gough's statement referred to previously.

Despite undertaking the research into the fatalities before the power of home-computing was available and prior to the invention of the internet, Martin Middlebrook did an amazing piece of work in extracting an exhaustive analysis of the fatalities incurred on that day. A modern re-analysis has shown that while some minor adjustments can be made to his figures, and it is possible to look at non-infantry deaths in more detail, the fatality figures that Martin Middlebrook extracted in the mid 1970's were extraordinarily accurate.

Article by David Tattersfield, Vice Chairman, The Western Front Association

Footnotes

(1) The Arras Memorial for the dead of the Third Army, the Pozières Memorial for the Fifth Army.

(2) Information extracted from www.cwgc.org. It should be noted that CWGC data on their web site is not 'static'. Any changes or corrections to the data are reflected on the commission's website, such changes would potentially make any downloaded data inaccurate.

(3) Machine Gun Corps casualties have proved very troublesome to correctly identify. The reorganisation of MGC Companies into MGC Battalions a few weeks before the German attack has resulted in the CWGC data being difficult to interpret. Many MGC fatalities are listed as belonging to MGC Companies rather than MGC Battalions. For example the CWGC list one officer and nine other ranks killed on 21 March from the 59th Company MGC. If taken at face value, this unit would (prior to February/March 1918) have been part of the 20th Division. The fact however that the men detailed by the CWGC are commemorated on the Arras Memorial to the missing indicate that they were part of the Third Army. It is therefore evident that the men were not 20th Division fatalities (20th Division, being part of Fifth Army have fatalities with no known grave commemorated on the Pozières Memorial). It is therefore certain that these men were part of the 59th Battalion (59th Division). A similar process had to be undertaken for a large proportion of the MGC casualties named by the CWGC.

(4) Some RFA Brigades were 'Divisional assets'. Other RFA Brigades were 'Army assets' and sent to sectors of the front that needed reinforcement. Fatalities in these 'Army Brigades, RFA' are not included in the data provided in the tables detailing divisional fatalities.

(5) RGA fatalities are discussed elsewhere in the article, but RFC squadron deaths amounted to five (35, 80 and 8 squadrons) and Tank Corps 14 fatalities (7 of these from the 6th Battalion). Labour Corps fatalities are difficult to pinpoint as many men are recorded as being regimentally elsewhere, but the 108th Company Labour Corps (recorded on the CWGC database as 37th Battalion Royal Fusiliers) seem to have become involved, losing 8 men killed. The 21st Entrenching Battalion lost 17 men killed, other Entrenching Battalions lost nine between them. (Entrenching battalions were formed around February 1918 from the surplus following the break-up of many infantry battalions . They were to hold reinforcements close to the front lines until battalions needed them. The men in the Entrenching Battalions worked under direction of the Royal Engineers, usually repairing roads and improving defences.)

(6) One example will suffice to illustrate this problem. The 1/4th and 2/4th battalions of the East Lancashire Regiment had, by March 1918, been merged into the 4th battalion (66th Division). On the 21 March 1918, eight officers and men are listed as being killed from the 1/4th East Lancs, 89 from the 2/4th Battalion and six from the 4th Battalion. Much work was undertaken to assign men to the (merged) battalions, but in a small number of cases there remains an element of doubt as to which battalion some men were serving with when they were killed.

(7) Again using the example of the 4th East Lancs, their commanding officer (Lt Col AL Wrenford) is listed by the CWGC as a Worcestershire Regiment officer but when extracting the data in bulk from the CWGC website, the fact that he was "attached 4th East Lancs" was not detailed in the downloaded spreadsheet. It is not possible to be certain that all such instances have been identified.

(8) A total of 183 men have dates of death between 21 March and a later date. There are significant 'blocks' of such 'uncertain dates' - 17 men from the 1st King's (Liverpool) , 56 men from the 1st Royal Dublin Fusiliers and 36 men from the 5th Gordon Highlanders are listed as being killed "between" 21 March and "a later date". For the purpose of this article, in all of these cases the assumption has been made that the men were killed on 21 March.

(9) General Sir Hubert Gough, Fifth Army (Hodder and Stoughton Ltd, 1931), p. 238.

(10) Fifth Army divisions were extended having 3.23 miles of front per division whereas the Second Army (around Ypres) had only 1.92 miles of front per division. See Martin Middlebrook, The Kaiser's Battle (Allen Lane, 1978), p. 71.

(11) See Middlebrook, Kaiser's Battle, pp. 373-375 which details 83 Brigade, RFA. This unit was part of 18th Division. This accounts refers to firing over open sights and defending the guns with small arms. This Brigade lost 15 other ranks killed - the third highest fatalities by a single RFA Brigade during the course of the 21 March.

(12) The RGA fatalities were in small clusters, no single battery losing more than eight men killed. The RGA battery with the highest fatalities would seem to be the 301st Siege Battery which lost 1 officer and 7 other ranks killed. This unit was in the Third Army sector on 21 March.

(13) Fatalities among Royal Engineers Tunnelling Companies numbered ten, and among the Special Companies (responsible for projecting gas)numbered eleven. But Railway Operating Companies also had fatalities, and even the Postal Section lost a man killed.

(14) Middlebrook, Kaiser's Battle, p. 227. This Field Company lost three men as fatalities.

(15) There is some difficulty in extracting meaningful data for TMB fatalities due to the use of infantry to man light batteries of mortars, the RFA who were deployed on the medium batteries and the RGA to man the heavy batteries.

(16) Just two instances of Medical Officers being attached to fighting units can be located among the fatalities of 21 March. One is Capt Evatt of 330 Brigade RFA (66th Division) and the other Capt Anderson of the 6th Black Watch (51st (Highland) Division). The 6th Black Watch suffered more fatalities than any other battalion in the 51st Division on 21 March.

(17) The National Archives (TNA): Public Record Office (PRO) WO95/2339: War Diary 16th Manchesters, March 1918.

(18) See footnote 8 above. The margin of difference for the 16th Division would be much reduced if we were to assume none of the men assumed to have died on 21 March were killed on that day. Similarly, for the 61st Division, the uncertain dates of death for men from the 5th Gordons would explain most of the difference between the figures provided.

(19) Barrie Thorpe, Private Memorials on the Western Front (WFA publication, 1999)