The Profitts…and Loss: A Cornish-Australian family at War.

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Profitts…and Loss: A Cornish-Australian family at War.

Porthilly Cove is a small, unspoilt inlet situated on the east side of the Camel estuary that cuts into the north Cornish coast. On the seaward lip of the cove sits the Rock Sailing and Water-ski Club, and to the south lay oyster beds upon the foreshore. Directly opposite, on the west bank of the estuary a short ferry-crossing away, is the historic fishing port of Padstow – home of the traditional ‘Obby ‘Oss Mayday festival and celebrity chefs. The surrounding area has become a playground for the well to do; yachting, water-skiing and windsurfing are popular pastimes of the affluent holidaymakers and second-home owners that flock here year after year. But the cove itself remains relatively untouched by all this activity, the main constant being the regular comings and goings of the oyster farmers whose forays onto the foreshore to tend to their crop – contained within mesh bags cradled on metal racks only exposed at low tide – provide the rhythm of the working day, in lockstep with the inexorable tidal movements of the Atlantic.

Above: Porthilly Cove – the roof of St Michael’s Church can be seen on the extreme left (Photo – Paul Blumsom)

Presiding over this tranquil scene is the church of St Michael, perched almost precariously, just a matter of feet from the edge of a small escarpment above the beach. Its burial ground is wrapped around the east, south and west aspects of the church, and within its bounds can be found the graves of generations of a number of local families, including the Profitt family.

Above: St Michael’s Church, Porthilly Cove (Image: northcornwallclusterofchurches.org.uk)

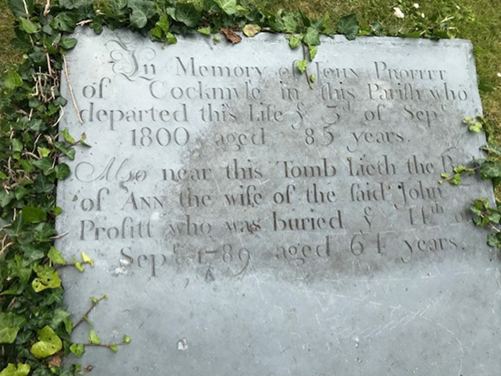

The surname Profitt derives from the Old French Prophete, originally a nickname, and modern-day variants include Profit and Prophet. Early recorded examples of the name include William le Profete (Berkshire Rolls 1220) and Gunnora Prophete (Essex Rolls 1327) [1]. The family has inhabited this area of north Cornwall for many generations – records date back to at least the sixteenth century – and includes farmers and mariners amongst their ranks. An early grave situated within the churchyard is that of John Profitt, born 1716, died 03/09/1800, aged 85 years.

Above: Gravestone of John Profitt 1716-1800 (Photo: Paul Blumsom)

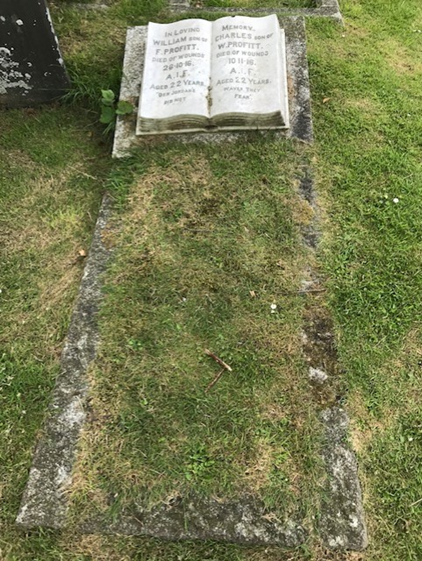

Also at rest here is John’s great great great grandson, Private 2208 William James Profitt, of the 23rd Infantry Battalion, Australian Imperial Force (AIF), who died from his wounds on 25 October 1916 at Cambridge Military Hospital, Aldershot, aged 22. Commemorated on William’s headstone, which is sculpted in the style of an open book, is his cousin – likewise descended from John – Lance Corporal 9028 (John Walter) Charles Profitt, of the 6th Field Ambulance, Australian Army Medical Corps, who died just over a fortnight after his kinsman on 10 November 1916 in France and was laid to rest there at Heilly Station CWGC Cemetery near Mericourt-L’Abbe.

Above: William James Profitt’s grave, St Michael’s churchyard, Porthilly (Photo: Paul Blumsom)

The cousins were both born in Australia. Their fathers, brothers Francis Profitt (1863-1943) and William John Profitt (1861-1943), left Cornwall for the antipodes to make a better life for themselves, joining the Cornish Diaspora of the 18th and 19th centuries. Francis arrived in Melbourne on 7 December 1888 and William followed just over a year and a half later, sailing from Plymouth on 19 July 1890. The brothers both married in 1894 and settled down in the Melbourne area to start their respective families and establish a furniture warehouse business.

Above: Profitt Bros., Furniture Warehouse, 95-97 Smith Street, Fitzroy, Melbourne, 1905 (Image – picturevictoria.vic.gov.au)

Private 2208 William James Profitt, 23rd Battalion, Australian Infantry, AIF

William Profitt was born in Collingwood, an inner-city district of Melbourne, Australia, to Francis Profitt and Mary Anne (née Smith) on 20 August 1894. He was educated at Melbourne High School, serving as a senior cadet in the army cadet corps during his time there. Upon leaving school at the age of 15, he secured employment with Du Rieu & Co. Printers, 9 Johnston Street, Collingwood, Melbourne, on a 5-year apprenticeship as a salesman, but retained his interest in the military; he became a part time soldier with the 55th Collingwood Regiment, Australian Militia, serving for 3 years. Upon the outbreak of the war in Europe, the Mother Country’s imperial subjects rushed to join up, and William duly enlisted in the last year of his apprenticeship – with his employer’s consent – on 5 July 1915, at the age of 20 years 11 months. He was posted to the 23rd Battalion, AIF, joining the 4th reinforcement on 20 July 1915. The battalion had been raised a few months previously in March 1915 and would form part of the 6th Brigade of the 2nd Division.

Above: Members of the 55th Infantry (Collingwood) Regiment, marching past officials after the presentation of the colours to the regiment, at Victoria Park, Collingwood, Victoria State (Image: Australian War Memorial)

He had previously tried to enlist as a regular but was rejected as unfit for His Majesty’s Service on the grounds of his height; he was 5’ 2½” tall, thus falling short of the 5’ 6” required. But his determination to serve would not be denied, the limit was reduced to 5’ 2” in June 1915, the urgent need for manpower allowing a relaxation in the height threshold. The 4th reinforcement of the 23rd Battalion embarked at Melbourne on 27 September 1915 and set sail on the HMAT Hororato for Egypt. William was formally taken on the strength of the 23rd Infantry Battalion on 11 January 1916 at Tell El Kebir: a reception and training centre for AIF reinforcements. Prior to William’s arrival the battalion had served in Gallipoli from September to December 1915. Following the failure of the Dardanelles offensive, the 23rd regrouped in Egypt in January 1916 for a period of consolidation and training where William joined them. He was there for just over two months before they received orders to mobilise, setting sail from Alexandria on 19 March 1916 upon the HMS Osmanieh, arriving at Marseilles on 30 March 1916, to join the BEF on the western front.

Above: Private 2208 William James Profitt, 23rd Infantry Battalion, Australian Imperial Force (Image: Australian War Memorial)

The 23rd, along with her sister battalions, the 21st, 22nd and 24th, that together formed the 6th Brigade of the 2nd Australian Division, were deployed in the (relatively quiet) Armentieres sector for approximately 3 months before moving to the Somme. They were billeted initially in the vicinity of Amiens and then Albert in preparation for a planned offensive at Pozières. The commune of Pozières straddles the Roman road that runs roughly southwest to northeast from Albert to Bapaume and the front line crosses the road at right angles, just west of the village. It was situated on a particularly high point on the Somme battlefield and an important position militarily and tactically: ‘…the ground to the immediate rear of the village stood on the very summit of the Thiepval-Ginchy Ridge, so that possession of this ground would secure the flank of any major advance by Fourth Army [and] the possession of this ground, and especially that around Mouquet Farm, would allow observation over the German positions around Thiepval from the rear’ [2].

The 1st Australian Division(who along with the 2nd and 4th Divisions made up the I ANZAC Corps) were chosen to lead the attack in the first instance, and on the night of 19/20 July relieved the British on a one-mile front south of the town. The attack went in on the 23rd after a postponement due to inadequate preparation. The village was swiftly taken, and the Germans driven out. The response was immediate, a series of counterattacks ensued but all failed. The Germans changed tack, and began a furious, sustained bombardment that would exact a heavy toll on the Australians. Further attempts to push on north of the village, including capturing a stronghold at Mouquet Farm, were unsuccessful; unsurprisingly so, as the 1st Australian Division were almost spent, having suffered 5,283 casualties since the start of the offensive. And so the stage was set for William to enter the fray. On the 26th, the 2nd Australian Division received orders to relieve the 1st Division, and the next day, the 23rd Battalion entered the trenches running northwest from Bailiff Wood, doing so under the continuing heavy bombardment that had pounded their predecessors.

Above: Men of the 2nd Australian Division resting by the roadside during the Battle of Pozières Ridge, 16th July 1916 (Image: Imperial War Museum)

The 6th Brigade war diary entry for 28 July 1916 read as follows:

Fine and warm. Front line Bns subjected to heavy bombardment. Orders received to attack ridge NW of Pozières on 650 frontage. 7th and 5th Australian Infantry Brigades attacked simultaneously. 23rd Battalion detailed to carry out attack with 2 Coys. 22nd Bn holding line in Pozières and available for reserve. Attack commenced at 12.15am. Both objectives won by 6th Brigade but owing to failure of 7th Brigade greater portion of captured position had to be evacuated. New position held was consolidated but only ⅓ of line attacked remains in our hands. Casualties estimates: Killed OR’s 24; Wounded Off 5 OR’s 231; Missing OR’s 4 [3].

The Official History of the War describes the events of 28/29 July:

‘…the 23rd Battalion of the 6th Brigade suffered no check in reaching the German trench along the Ovillers-Courcelette track. Unable to recognize their shell-shattered objective, the two leading waves of Victorians pressed on and suffered heavily from their own barrage before they could be brought back to their proper line. A thick fog proved of great advantage during the work of consolidation. The failure on the right obliged the battalion to relinquish part of its gains and to throw back a defensive flank along the track leading to the cemetery. The right of the II Corps had made no attack, with the exception of an effort of the 11/Middlesex (36th Brigade) to capture the extension of Western Trench by an advance over the open. This movement was checked by bombing and rifle fire. The 23rd Battalion, therefore, held a narrow salient, pointing north-westward, along the Pozières ridge in the direction of Mouquet Farm’ [4].

Above: Machine Gun team at Pozieres (Image: Australian War Museum)

The 6th Brigade war diary entry for 29 July 1916 continues:

Fine and warm. 24th Bn withdrawn from front, left half of line held by 23rd Bn. At 10 p.m. 21st Bn relieved 22nd Bn. Position heavily shelled including gas shells at night. Preliminary arrangements made with a view to completing task of capturing original objective – but were hampered by heavy shell fire. Casualties estimates: Killed Off 1, OR’s 24; Wounded Off 5 OR’s 288; Missing Off 3 [5].

That morning at Anzac Corps HQ it was decided to renew the attack on the night of the 30/31 of July, despite the fact that the 2nd Australian Division had already suffered the loss of 3,500 officers and men; killed, wounded and missing. This decision was taken under extreme pressure from the high command who would brook no delay. However essential preparatory groundworks were necessary and would delay the offensive.

6th Brigade war diary entry for 30 July 1916:

Fine and warm. At 7 a.m. 23rd Bn withdrawn: whole front now held by 21st Bn. Lt. Col Hutchinson, 21st Bn evacuated with shell shock. Major F Forbes assumed command 21st Bn. Usual heavy shell fire maintained. Defences improved but not pushed forward. Middlesex Regt on left relieved by Sussex Regt. Casualties estimates: Killed Off 1, OR 10; Wounded Off 3, OR 163; Missing OR’s 34[6].

As the relief of the 23rd Battalion took place, William sprained his ankle. His Casualty Form – Active Service describes the nature and circumstances of his injury as ‘…trivial, will not interfere with his efficiency, occurred on 30/07/16. Being relieved from trenches slipped and fell into old German dugout was in no way to blame’ [7]. He entered the medical chain of evacuation, being treated initially at the 3rd Casualty Clearing Station before admission to the 13th General Hospital, Boulogne. William continued his recovery at Étaples, having been admitted on 13 August 1916. For now, he was safe.

On 24 August 1916, having recovered, William rejoined the 23rd Battalion in the field at Pozières. The 6th Brigade were tasked to attack Mouquet Farm – known to the troops as ‘Mucky Farm’ – a strongpoint around a thousand yards to the north of Pozières and fortified by a system of excavated dugouts linked to existing cellars, to commence on 26 August 1916 at 04.45am, led by the 21st Battalion. This was a daunting prospect:

‘The operation against Mouquet Farm was fraught with danger, both for the Australian troops and for those of II Corps. The advance they would be making would take place on an exceedingly narrow front. Moreover, the Australians on the right would attempt the advance along the very crest of the ridge. All their troop movements would be easily observable by German forces around Courcelette, who would be able to direct machine-gun and artillery fire against them. In addition the advance would create a salient which could be brought under fire from many directions – from Courcelette on the right, from Thiepval almost directly ahead, from Grandcourt to the north, and even from Martinpuich to the southeast. And most dangerous of all for the attackers, enemy artillery could not only fire in enfilade but directly along the trench lines which led to Mouquet Farm. Of all the tactical nightmares on the Somme this has some claim to be considered the worst’ [8].

Above: The cellars under Mouquet Farm. Practically a fortress, very fierce fighting took place for its possession, and it changed hands several times (Image: Australian War Memorial)

Early in the morning of the 26th, the 23rd Battalion came under fire. From 01.00am onwards German trench mortar bombs started to rain down on digging parties working in forward positions of their sector of the line. The right flank of the battalion suffered a number of casualties from these shells. The Germans’ vantage point upon the plateau afforded them an excellent view of the Australian trenches and they were taking full advantage of it. The casualty figures listed in the war diary for the whole of the 6th Brigade on the 26th of August were: Killed: 4 officers, 41 other ranks. Wounded: 7 officers, 250 other ranks. Missing: 3 officers, 132 other ranks [9].

Above: 28th August 1916, Australian stretcher bearers passing the old cemetery of Pozières, having come out of the line near Mouquet Farm (Image: Australian War Memorial)

During the fighting at Pozières and Mouquet Farm, the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) lost almost as many men over seven weeks as it did throughout its eight months on Gallipoli, three AIF divisions suffering 23,000 casualties. Of these, 6800 were killed or died of wounds.

Above: Troops of the 2nd Australian Division returning from the trenches after the Battle of Pozières. Near Contay, August 1916 (Image: Imperial War Museum)

William was amongst those wounded in action on the 26th, suffering a severe gunshot wound (GSW) to his right elbow. He was evacuated to the 9th General Hospital, Rouen, arriving on the 28th, before embarking for England on the HMHS St Patrick on the 31st. William was admitted to Cambridge Hospital, Aldershot, on 2 September 1916. The Transfer Certificate described his wounds as follows:

’…head of radius found shattered, considerable ecchymosis and swelling of the forearm, good radial pulse. Fixation on right. Description of wound is ankle splint. There is a small discharging wound over head of radius about as large as a shell and circular with a gauze ram. Some retained discharges in forearm below and out to wound. A small scabbed wound 2 inches lower greatly swollen and painful.’ An X Ray revealed a ‘Communicated fracture of shaft of radius just below neck displacement slightly backwards of lower fragment. Piece of metal junction of middle and upper third of forearm.’[10]

Over the next few days, William’s treatment consisted of the insertion of drainage tubes to enable the retained discharge to exit the forearm; along with the application of gauze and of syringing out the wound. However, it didn’t work, the discharge was not draining and his shoulder swelled alarmingly. On 14 September 1916, the following procedure was carried out: ‘Under ChC13[Chloroform]wound enlarged, many pieces of necrosed bone removed and a large piece of metal. Larger drainage tube passed through.’{11]

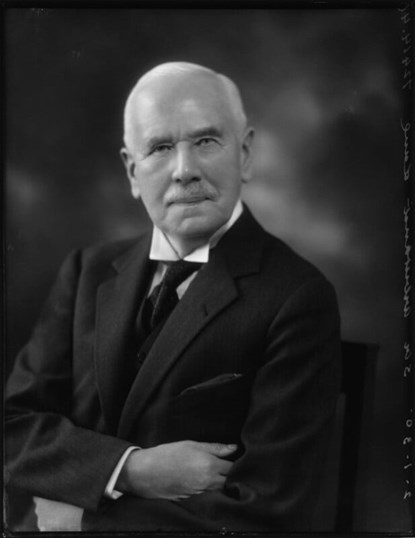

His condition failed to improve satisfactorily over the following weeks. As a result, on 8 October the decision was taken to amputate the arm just above the elbow. The procedure was carried out the following day. This also proved unsuccessful; William’s condition was described as ‘poor’. On the 11th, a further operation took place, performed by the eminent surgeon, Sir Arbuthnot Lane, who ‘…removed a couple of inches more of bone and packed the cavity with gauze, soaked in sulphur and glycerine. There is oedema of arm and chest wall. Fomentation applied.’[12]

Above: Sir William Arbuthnot Lane CB FRCS RAMC, Consulting Surgeon at Cambridge Military Hospital, Aldershot (Image: National Portrait Gallery)

Unfortunately, this intervention failed also. By the 24th, William’s notes state that he was struggling to breathe: ‘…Breathing difficult. Needle inserted and a syringe full of blood-stained serum withdrawn. Breath sounds deficient, and crepitations heard over both bases. Aspirated chest and 20 oz of fluid withdrawn. Pulse 146. Much weaker and wandering. Saline transfusion intravenous getting weaker, almost unconscious.’[13]

On the 25th William’s brave fight to survive ended, he passed away peacefully from acute septicaemia, his last moments described as: ‘Quite unconscious and smiling. Died at 3:45pm.’[14]

William’s Cornish relatives scooped up his broken body in a familial embrace and laid him to rest, surrounded by his ancestors, at St Michael’s, Porthilly, far, far from home.

Lance Corporal 9028 John Walter Charles Profitt, 6th Field Ambulance, Australian Army Medical Corps

John Walter Charles Profitt (known as Charles) was born in June 1894 to William John Profitt and Harriet (née Smith) in Geelong, Victoria, around 50 miles southwest of Melbourne. Charles was educated at Melbourne High School and served with the school army cadet force for 12 months whilst there. After leaving school, he became a teacher.

Charles enlisted on 9 July 1915 and was posted to the AIF Depot at Seymour Training Camp, Victoria, approximately 100km north of Melbourne, until 13 August 1915, when he was transferred to the Clearing Hospital at Broadmeadows Camp where he served until 11 January 1916. On 21 January 1916 he was appointed to the Royal Australian Army Medical Corps, 6th Field Ambulance unit, 6th Infantry Brigade, with the 9th reinforcement. He embarked from Melbourne on board HMAT A32 Themistocles on 28 January 1916, arriving in Egypt on 29 February 1916. He was officially taken on the strength of the 6th Field Ambulance on 10 March 1916.

Above: Lance Corporal 9028 John Walter Charles Profitt, 23rd Infantry Battalion, 6th Australian Field Ambulance, Australian Imperial Force (Image: Australian War Memorial)

His time in Egypt coincided with that of his cousin William, and they would undoubtedly have sought each other out whilst there, as Charles’s unit was the Field Ambulance Company attached to the 6th Infantry Brigade, parent Brigade to William’s 23rd Battalion. They both embarked from Alexandria – on separate ships – for France on the same day, 19 March 1916. Charles travelled on the HMHS Llandovery Castle and arrivedat Marseilles four days earlier than William on 26 March 1916. The 6th Field Ambulance were transported northwards by train, arriving at Aire on the 29th at 01:30, whence they detrained and marched off with the 22nd Infantry battalion AIF, arriving at billets in Warne at 05:00, the 22nd Btn continuing to Roquetoire. On the 31st, the unit war diary details that they attended a ‘parade and inspection by Lord Kitchener near Aire.’[15]

On 9 April 1916 they moved to Erquinghem near the Belgian border, where they were stationed in support to the 6th Infantry Brigade who were deployed in the nearby Armentieres sector. On 6 July 1916, they were redeployed to the Somme, along with the rest of the 2nd Division.

As the 6th Field Ambulance were a vital link in the medical chain of evacuation, Charles is likely to have been well aware of his cousin’s injuries, both on 30 July 1916 when William sprained his ankle and on 26 August 1916 when he suffered the far more serious GSW to his right arm. On the former occasion the 6th Field Ambulance were stationed at Warloy and at nearby Vadencourt for the latter, and during this period, on 18 August 1916, Charles was promoted to Lance Corporal.

Above: Unidentified members of the Australian Army Medical Corps dressing the wounds of Australian soldiers in Becourt Chateau during the battle of Pozieres. At the time the chateau was occupied by a field ambulance of the 2nd Australian Division and a British field ambulance (Image: Australian War Memorial)

On 9 November 1916, Charles suffered a gunshot wound (GSW) to his stomach and was admitted to the 15th Field Ambulance, 1st ANZAC M.D. Station, on the 10th. He was then transferred to the 36th Casualty Clearing Station (CCS) where he died the same day from his wounds, described as a GSW abdomen – bowel protruding[16].

The 6th Field Ambulance war diary entry for 9 November 1916 mentions Charles’s wounding after the rest of the day’s events: ‘DDMS [Deputy Director Medical Services] 1st Anzac inspected all arrangements and expressed himself satisfied. Accompanied DDMS to Quarry Siding to arrange evacuation by train. Also inspected railway at present under construction from Bazentin Circus to Longueval. Wounded Off 3 OR 62. Sick Off 2 OR 165. ADVS [Assistant Director Veterinary Services]called inspected horses and promised rugs and extra rations, horses are feeling the cold and extra work. 9028 L/Cpl Profitt JWC wounded.’[17].

He was buried at Heilly Station CWGC Cemetery, the burial ground established on the site of the 36th CCS in May 1916, 2km southwest of Mericourt-l’Abbe.

Above: Heilly Station CWGC Cemetery, Mericourt-L’Abbe (Image: ww1cemeteries.com)

The deaths of the two cousins within such a short space of time hit the family hard, and as a result their Cornish relatives chose to commemorate Charles’s passing on William’s headstone. They selected an inscription for them both paraphrasing a hymn by Charles J Butler, O’er Jordan’s waves they will not fear, adapted from the first verse:

Some day, I know not when ‘twill be,

The angel death will come to me;

But this I know, if Christ be near,

Old Jordan’s waves I will not fear.

Above: Headstone of Private William James Profitt, St Michael’s churchyard, also commemorating his cousin Lance Corporal (John Walter) Charles Profitt (Photo: Paul Blumsom)

There is a deeply moving postscript to the story of the two cousins. In May 1929, William’s father, Francis Profitt, at the age of 64, travelled all the way from Australia to Cornwall with his 18-year-old daughter Phyliss, to visit his boy’s grave at St Michael’s. He spent the whole summer in Cornwall, from 23 May 1929 to 25 September 1929, and it is entirely possible that he also visited his nephew’s resting place in France whilst there. His visit coincided with the battlefield tourism boom of the late 1920s – early 1930s; the British Legion had instituted organized tours from the UK – in effect pilgrimages – for veterans and relatives of the fallen in August 1928, shortly before Francis’ arrival. In any case, his own paternal pilgrimage had brought him back to his birthplace, 41 years since he’d left, and if there could be one place that would provide him with solace, some inner peace, then this corner of Cornwall, where he was born and bred, was that place. The image of Francis standing by William’s grave, gazing out over the estuary, is a haunting one – the mighty Atlantic before him, the waves lapping the shore below, his boy at rest in his ancestral homeland.

Above: The view from St Michael’s Church across the estuary to Padstow (Photo: Paul Blumsom)

Above: The mouth of the Camel Estuary opening out to the Atlantic Ocean (Photo: Paul Blumsom)

Article by Paul Blumsom

References

- Reaney, P.H., A Dictionary of British Surnames, Routledge and Keegan Paul, 1979, p.283.

- Prior, Robin and Wilson, Trevor, The Somme, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2005, p.175.

- AWM/4, AIF Unit War Diaries, 1914-18 War, Infantry,23/6/11, 6th Infantry Brigade, July 1916, pp.12-13.

- Miles, Captain, W. Official History of the War: Military Operations France and Belgium 1916, Vol. 2, Reprint by Battery Press, Nashville, Tennessee, originally published Macmillan 1938, p.155.

- AWM/4, AIF Unit War Diaries, 1914-18 War, Infantry, 23/6/11, 6th Infantry Brigade, July 1916,p.14.

- Ibid., pp.14-15.

- National Archives of Australia (NAA), Series Number B2455, Profitt William James, p.2.

- Prior, Robin and Wilson, Trevor, The Somme, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2005, p.180.

- AWM/4, AIF Unit War Diaries, 1914-18 War, Infantry, 23/6/12, 6th Infantry Brigade, August 1916, p.14.

- Australian Red Cross Society Wounded and Missing Enquiry Bureau Files, 1914-18 War, 1DRL/0428, 2208 Private William James Profitt, 23rd Battalion (unpaginated).

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- AWM/4, AIF Unit War Diaries, 1914-18 War, Medical, Dental & Nursing, 26/49/11, 6thAustralian Field Ambulance,February-March 1916, p.11.

- NAA, Series Number B2455, Profitt John Walter Charles, p.3.

- AWM/4, AIF Unit War Diaries, 1914-18 War, Medical, Dental & Nursing, 26/49/13, 6th Australian Field Ambulance, November 1916, p.5.

Other Sources:

Passenger manifest of the SS Cuzco dated 19/07/1890 Plymouth to Melbourne

Passenger manifest of the SS Orient dated 07/12/1888 Plymouth to Melbourne

Passenger manifest of the SS Oronsay dated 23/05/1929 Melbourne to Southampton.

Passenger manifest of the SS Balranald dated 25/09/1929 Plymouth to Melbourne.

Keech, Graham, Pozières: Battleground Europe, Pen & Sword, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, 2015.

Lloyd, David. W, Battlefield Tourism, Bloomsbury Academic, London, 1998.