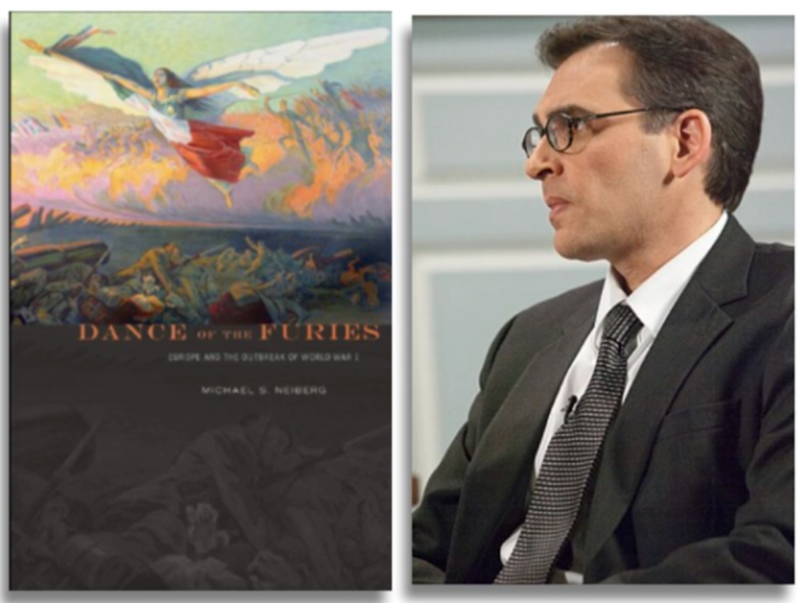

Dance of the Furies: Europe and the Outbreak of War, 1914 - Michael S. Neiberg

- Home

- World War I Book Reviews

- Dance of the Furies: Europe and the Outbreak of War, 1914 - Michael S. Neiberg

336 pages

Belknap Press

Publication Date: 10/14/2013

ISBN 9780674725935

‘Dance of the Furies’ by Michael S Neiberg is a definitive social history of Europe leading up to the outbreak of world war, its initial spasms and the first months of the conflict.

‘Dance of the Furies’ is a comprehensive academic study into the lives of those who were living right across Europe when war broke out in July/August 1914. There were people who wanted change (but not if it meant war) and people content with life as it was who wished to keep it that way (but not if it meant war). Next to no one cared for the violent spits and spats on the edges of the old established empires, though plenty despaired of their politicians and rulers and how they ruled. Short localised wars came and went, there were assassinations a plenty, empires persisted, industry and trade grew, there was a burgeoning Press.

Michael S.Neiberg is a polyglot; in ‘Dance of the Furies’ he picks through hundreds of diaries, memoirs, letters, papers, national and regional newspapers; he even includes a French teachers’ newspaper and socialist union reports. He read multiple authors from across Europe: from Germany to France, Britain to Spain, Austria and Hungary, Russia and Serbia. Everything is referenced and the bibliography is extensive.

These are, in Neiberg’s words, the stories of ‘ordinary Europeans’, who, ‘unlike their military leaders neither wanted nor expected … war’. Far from being ‘rabid nationalists’ as later portrayed ‘Europeans’ were ‘shocked, repulsed and fearful’ at the prospect of war and its ‘ghastly, protracted orgy of violence’.

Having written an MA thesis on ‘enthusiasm for war’ in England in September 1914 my reading was already wide - if confined to Britain. ‘Dance of the Furies’ does for all of Europe, with Britain and Ireland important bit players, what Catriona Pennell achieved with ‘A Kingdom United’ and what I did for volunteers from southern Wales and East Lancashire - mostly working class men, with a middle class element in the Cardiff Pals and a smattering of well educated upper middle class sons of professionals.

Reading ‘Dance of the Furies’ reinforces my understanding of the reality of the feelings leading through the coming of war and then the behaviours and feelings once war broke out and men were encouraged to enlist. Feelings changed gradually over a number of weeks and days from fear and anxiety to duty and intentions to the need to see a job through to enmity - even a desire for vengeance’ (pp.136/137) News that Germany had invaded neutral Belgium arrived on August 4 and instantly changed British attitudes (p.143) … both to Germany and to Germans. (p.144) While there was distinct unease at going to war amongst Russians (p.145)

Adrian Gregory, another important authority on this period, wrote that there was ‘unexpected rise in unemployment, as workshops, cafes, restaurants, building sites closed’ and that this ‘may have contributed significantly to British men’s willingness to volunteer’. (Adrian Gregory, C6. p25) Across Europe, Neiberg explains, there were shortages, inflation in prices of goods and rents, then propaganda compounded by a mixture of a lack of news or false news. People understandably were more fearful than enthusiastic for war - more concerned for their own domestic circumstances.

It was a myth that nations, their soldiers and citizens were at all enthusiastic about going to war in 1914.

‘Dance of the Furies’ is both essential reading and an essential reference for anyone wishing to understand why the world went to war in 1914 and what the people of Europe felt about before, during and after the outbreak of war.

Review by Jonathan Vernon (Digital Editor) September 2021

Additional notes and references for students

Neiberg sets out six arguments regarding the outbreak of war in 1914:

- ‘the people’ did not want war;

- the complexity of class, gender, ethnicity, religion, education and family meant that ‘nationality’ was a spurious concept; the Alsatians were ‘above all, Alsatian’ - ‘French by culture, Prussian by government, and Bavarian for economics’ (p.59)

- all felt they were on the defensive (albeit Germany’s modus operandi was to knock out France via an invasion of neutral Belgium before stopping and defeating the ‘Russian hordes’); that all were ‘victims of German militarism’; foreign ministers of major powers, not least Germany and France, but including Britain, had failed to curbe Italy’s adventurism into Libya and beyond.

- where there was rupture, between British and Ireland, or within the Austro-Hungarian Empire, or between the Socialists in Germany and their government;

- pleas for unity in the initial crisis were heard.

- Societies kept fighting despite themselves once war had started, that the cost of defeat was always thought to be worse.

‘The blame’, Neiberg tells us, ‘for the outbreak of war’ rested with a ‘small group of German and Austrian military and diplomatic leaders who ‘badly misread the situation in 1914 … ‘ (p.4) At the head of this list we should put Kaiser Wilhelm II who ‘took Europe to war - having listened to at most 12 advisers’ (p.5) [Leopold Berchtold, Austro-Hungary Foreign Minister; Franz Conrad von Hötzendorff, Army Chief of Staff … Colonel von Leipzig] Who Jean Jaures associated with ‘absolutism, expansion, oppression, and Prussian-style militarism.’ (p.77) Had Germany been interested in arbitration war could have been averted (p.82).

The only danger, wrote the widely travelled Dane Georg Bandes, ‘came from the ability of leaders to excite war enthusiasm among the population’ - he wrote in 1913, putting blame for an escalation of tension down to ‘senior leaders in the military, large industrialists and chauvinistic journalists …’ (p.64)

Few believed in July 1914 how close they were to war. Herbert Adams Gibbons wrote that ‘I have been waiting 25 years for your European war. Many a time it has seemed as imminent as this - but it will not come!” (Paris Reborn, 1915). H G Wells had an inclining but war was thought to have become too expensive for governments to afford (p.57) There was a belief that the economic structure of Europe would put a brake on war.

In June 1914 most people had other things on their minds: earning a living, keeping a roof over their heads and food on the table. In France the trial of Henriette Caillaux for the murder of newspaper editor Gaston Calmette was the biggest story; in Great Britain there was a threat of civil war in Ireland, the suffragettes were active across europe, their were industrial strikes in Russia and Germany, and for those who could afford to do so, there was a summer vacation to take. Some were plunged into dire straits, such as the British woman who had a child by a German who was called up. Unmarried she had no support, nor was she allowed to work.

Neiberg point out that ‘another crisis in the Balkans’ was just that - and assassinations go, there had been plenty of these over the last two decades, and more often than not of a significant royal or political, from the president of France (1894) to the Premier of Spain (1897), the Empress of Austria (1898), the King of Italy (1900), the King of Portugal (1908), another Premier of Spain (1912) and the King of Greece (1913). The assassination of Archduke Ferdinand and his wife was just ‘another tale of blood in the annals of the ill-fated House of Hapsburg’ wrote the Irish Times.

There’s no doubt that Britain was dragged into the war under her obligation of the 1839 treaty guaranteeing Belgium neutrality, the purpose of which, was to keep the Channel Ports free from enemy occupation.

Neiberg six arguments are well made.

The Rise of Patriotism

Patriotism was a consequence of war, not the cause. It united people in new ways as the threat of invasion meant that people buried their partisan and class differences (to a degree) while sharing a national emergency.

With the threat of war came protests; 50% of departments in France held anti-war demonstrations on 31 July and 1 August 1914. A pan-European general strike was called for by socialists but collapsed as a genuine sense of fighting for national survival took hold. (pp.106-107)

There were key tripping points, from the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum to Serbia to Germany’s demand that France announce that it would not participate in a Russo-German war and that as an assurance of neutrality they would have to hand over the forts of Verdun and Toul. (p.112)

The assassination of the French socialist leader Jean Jaurés 31 July 1914 was of far more interest and consequence to the French people than the assassination of Franz Ferdinand. Jaurés was personally still seeking ways to prevent war when he was assassinated while in a meeting with friends and colleagues in a Paris cafe..

Let War Begin

‘Armageddon begins’ wrote Rudyard Kipling.

The sudden speed of events contributed greatly to the sense of confusion, disorientation and helplessness that many people felt. Far from enthusiasm, people began to feel resigned to war with a building sense of determination to see it through. There was a sense of ‘fear, dread, and a terrible sense of uncertainty’.

‘It came in the end like a thief in the night, quite unexpectedly’ wrote Charles Repington the Journalist and later author of ‘The First World War’.

The need for self-defense morphed seamlessly into justification for an aggressive, offensive war of conquest.

The press wildly exaggerated the enthusiasm of people’s response to war. (p.134)

Britain was united in its view by Germany’s invasion of Belgium, otherwise the country ‘would have been ‘split end to end’ Sir Edward Grey is quoted as saying (in Malcolm Brown’s IWM Book of World War One).

Many young men had volunteered to fight in part out of a desire for adventure in a world that they thought had become too industrial, too predictable, and too stultifying. (p.188)

Hatred had not caused the war but the war quickly created hatred sufficient to ensure its prosecution to the bitter end. (p.207)

In conclusion

War broke out because a select group of a dozen men willed it or stumbled incompetently around a situation that they thought they could control until it was too late to stop the machinery they had set in motion. (p.234)

The overwhelming response of the people of Europe was not enthusiasm or joy but sadness and resignation. (p.235)

In discussion at the Carnegie Council > Dance of the Furies

Further Reading:

A Kingdom United by Catriona Pennell