Fighting For The Rufiji River Crossing: The British 1st East African Brigade in action German East Africa, 1 to 19 January 1917

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Fighting For The Rufiji River Crossing: The British 1st East African Brigade in action German East Africa, 1 to 19 January 1917

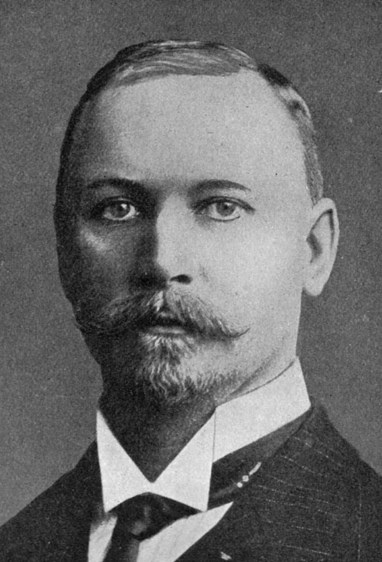

In September 1916 the British theatre commander in East Africa, General J C Smuts, had been forced to halt his advance when he reached the Mgeta River. The reason for this halt was the collapse of the British logistical support system that was dependent on undernourished and overworked African porters, many of whom dropped dead on the job or succumbed to disease. Very often the administrative arrangements for the clothing and feeding of porters and for the caring of the sick were deplorably basic, and a number of Europeans in the theatre appear to have considered porters as being expendable. Fortunately many European missionaries in East Africa volunteered to serve with porter units and this, combined with better centralized management of military labour, led to improvements in administration. However, throughout the campaign the numbers of porters required to support British operations were never acquired by the recruiting teams; the Germans displayed a more pragmatic and ruthless edge to their recruitment, requisitioning porters from villages by force when necessary. To General Smuts, a former South African guerrilla leader, logistics was a subject that he appeared not to want to comprehend; certainly he spent little time discussing it until he had to halt on the Mgeta.

Above: Jan Smuts in 1914

During this three-month halt it was decided to repatriate nearly all the white South African units that had arrived in late 1915 and early 1916, as they could not cope with the climatic conditions. Also white replacements from South Africa were not surviving long in the theatre, often because of poor medical selection procedures and inadequate recruit training. One example of this was a draft of 1,011 white South Africans that landed at Mombasa in late September; by the time this draft passed through Handeni which was 65 marching kilometers from the railhead at Korogwe, only 329 men were still marching. Sickness and sore feet had decimated the ranks. Fortunately the coloured South African Cape Corps battalion, although affected by disease, was a unit that could march and fight better than most others.

Indian units landed in 1914 had also lost men to malaria and other tropical ailments to the point of being ineffective for military operations. Most of the sepoys were debilitated not just by disease but also by inadequate food. The preparation of food for Indian soldiers was a more lengthy process than that required for Europeans and this aspect of administration was not always appreciated by the military planners. Often the sepoys had to eat semi-raw or barely-cooked food, just as the African porters did. The issue of the correct scales of rations for Indian troops was hampered by the shortage of porters and by the often large-scale pilfering that occurred on the lines of communication. South African and other rear-echelon troops regularly looted the rations and personal kits of the sepoys who were fighting at the front. The worn-out Indian battalions were now exchanged for fresher Indian Army battalions from India or Egypt.

White British units had also succumbed to the tropical conditions, and both the 2nd Battalion the Loyal North Lancashire Regiment and the Royal Naval Armoured Car Battery were sent to Egypt. However, the situation was not all doom and gloom for the British, as very effective African infantry and artillery units were arriving from Nigeria, Gambia and the Gold Coast. Many of these West African soldiers had fought in the Cameroons campaign. Also the four King's African Rifles regiments were each adding a third battalion to their strength.

The capture of the badly damaged Central Railway running from Dar Es Salaam to Lake Tanganyika, and its restoration and management by the Indian Army Railway Corps, materially improved the British logistical arrangements. This was augmented by the building of motorable roads from the railway south to the Mgeta, and by the liberal use of felled timber to throw bridges across the river. By late December, General Smuts' Field Force was ready to fight forward to its next objective, the south bank of the Rufiji River. The only uncontrollable factor was the weather - when would the seasonal rains start?

The 1st East African Brigade

The British plan involved advances by South African units in the west supported by Indian pioneers, sappers and miners and mountain artillery. In the east were two columns of Nigerians supported by Indian infantry. In the centre was the 1st East African Brigade consisting of:

- 25th Royal Fusiliers (220 rifles + 2 machine guns [mgs]).

- 30th Punjabis (520 rifles + 4 mgs).

- 130th Baluchis (450 rifles + 4 mgs)

- 3rdKashmir Rifles (150 rifles + 4 mgs).

- No 3 South African Field Battery (4 x 13-pounder guns).

- No 6 Field Battery (2 x 12-pounders).

- No 7 Field Battery, less one Section (2 x 15-pounders).

- No 13 Howitzer Battery (1 x 5.4-inch howitzer).

- a half double-coy of 61st Pioneers.

- one Section of East African Pioneers.

- one Section of Faridkot Sappers & Miners.

- No 1 Armoured Motor Battery (4 x machine guns).

- a Section of No 5 Armoured Car Battery.

(Recently a shell had exploded prematurely in one of the 5.4-inch howitzers of No 13 Battery, wrecking the gun and killing one and wounding two of the gunners.)

It was planned that the 1st East African Brigade, commanded by Brigadier General Seymour Hulbert Sheppard, Royal Engineers, would trap the German forces being pushed south from the Mgeta by the eastern two columns. Meanwhile the South African column to the west was to make its own crossing of the Rufiji and then swing east to destroy German units withdrawing south of Kibambawe, where a good bridge had been built by the Germans.

The 130th Baluchis advance

On New Year's Eve 1916 the attack began, it having been postponed from Christmas Day because of torrential rain that impeded movement until the ground had dried out. The 130th Baluchis crossed the Mgeta, capturing a forward enemy position and finding that the Germans in it were inebriated; the remaining German champagne was removed to the Baluch officers' mess. The Baluchis had been tasked with operating to the west of the brigade column in order to block the enemy from retreating through Wiransi. A double-company was detached to march to Wiransi whilst the remainder of the battalion cut the road from that village to Dakawa, and then advanced northwards to confront the withdrawing enemy.

Marching southwards on a collision course with the Baluchis was a German detachment under the command of Lieutenant Udo von Chappuis. His detachment consisted of:

- 1st Schutzen Company (white settler volunteers from pre-war rifle clubs).

- Wangoni Company (Askari recruited from the Wangoni tribe).

- 14th Reserve Company (Askari and police mobilized reservists).

- One 6-centimetre field gun named a Colonial Gun.

Around 0730 hours the Baluchis encountered an enemy picquet near the Kipiruta stream. An hour later a strong German attack supported by two machine guns was delivered onto the Baluch advance guard. Heavy fighting ensued and von Chappuis' men got around the Baluch left flank and made a bayonet charge. But the Baluchis were not relinquishing any ground and they counter-charged into the enemy ranks, fighting man-to-man with the bayonet until the Germans were thrown back. Then a German charge on the opposite flank nearly over-ran a jammed Baluch machine gun; again the Baluchis stood firm, rescuing the gun and holding the firing line. Von Chappuis maintained pressure on the Baluch position until the sound of firing could be heard further north, signaling that the British brigade column was getting closer; then the enemy broke contact and moved off through the bush, by-passing Wiransi.

The Baluchis had fired over 15,000 rifle rounds and 5,750 machine gun rounds. They had lost Jemadar Saidan Khan and 35 sepoys killed, and 29 other men were wounded. Twelve enemy Askari corpses were found, and two wounded Germans and a few wounded Askari were captured.

Above: An Askari company ready to march in German East Africa (Deutsch-Ostafrika)

The 130th King George's Own Baluchis (Jacobs' Rifles) had achieved their mission with distinction. Acting Captain John Gwatkin Steel, 130th Baluchis, was wounded during the fighting and later received a Military Cross:

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty when in command of the firing line during a stiff engagement which lasted for four hours. He kept his Commanding Officer well informed of the progress of the fight, and inspired his men throughout by his splendid example of courage and determination.

The Indian Distinguished Service Medal was awarded to:

69 Private Chaman Khan, 304 Lance Naik Fateh Muhammad, 3183 Naik Muhammad Hussain, 4006 Havildar Sultan Khan and 4996 Private Shah Baz Khan.

The 1st East African Brigade then marched down to Wiransi. Next day, 2nd January 1917, the 130th Baluchis and the 3rd South African Field Battery marched eastwards to Behobeho Kwa Mahinda to assist a column to the east, whilst the remainder of the brigade marched on tracks through the bush towards the Fuga Hills and onwards to Behobeho Chogawali, hoping to destroy von Chappuis' detachment.

The action at Behobeho Chogwali

During 3 January, 1st East African Brigade made an exhausting cross-country march culminating in a 60-metre descent over a field of huge boulders. This stretched the column out and considerably slowed down the porters carrying the machine guns, reserve ammunition, water and rations. The Brigade Commander halted his exhausted men for the night a few kilometers short of the destination.

The following morning at dawn 25th Royal Fusiliers led the advance followed by 3rd Kashmir Rifles and 30th Punjabis. Behobeho Chogawali was reached without incident and the advance turned north to Behobeho Kwa Mahinda. At about 1030 hours contact was made and the Fusiliers deployed onto a ridge beside the road; two companies of the Punjabis came up in support and the Kashmiris extended the Fusiliers' left flank. Ninety minutes later Wangoni Company came into view from the north and the Wangoni Askari, relatives of the Zulus, immediately attacked the British-held ridge. A lively and lengthy action then developed but the Fusiliers held their ground, efficiently using their two Maxim machine guns and two Rexer light machine guns.

The 25th Royal Fusiliers (Frontiersmen) lost Captain F C Selous DSO, 13285 Sergeant George Cornelius Knight, 32887 Private Edward William Charles Evans and 14885 Private David Edward Taylor killed in action. Second Lieutenant Ernest James Dutch later died of wounds; nine other Fusiliers were wounded including two officers. The 30th Punjabis lost 4142 Naik Gurdit Singh killed in action and three sepoys were wounded.

The biggest problem for the British troops was the heat and intensity of the sun, and this was compounded by the white crystalline stone that covered the ridge being held. This stone reflected the sun's rays, severely burning exposed skin. The Germans only broke contact when the 130th Baluchis approached from the north.

The death of Captain Frederick Courtenay Selous DSO

As listed above, this famous hunter was killed during the Behobeho action. He was 64 years old but had come to Africa with the 25th Royal Fusiliers where he commanded a company and was awarded a Distinguished Service Order:

For conspicuous gallantry, resource and endurance. He has set a magnificent example to all ranks, and the value of his services with his battalion cannot be over-estimated.

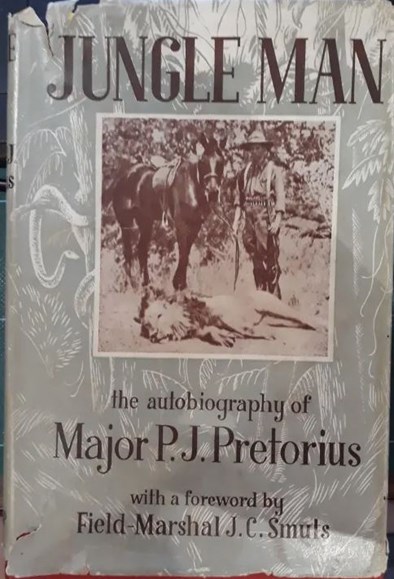

He was transferred onto intelligence duties where he obtained information on the enemy's positions and strengths by using African scouts. Major Philip Jacobus Pretorious DSO was Chief Scout for General Smuts, and in his book Jungle Man Pretorious wrote:

I remember General Smuts coming to me one day and personally countermanding an order he had given me overnight. This was to act as guide on an excursion to Behobeho; the new order was to lead the Cape Corps to the Rufiji, while Selous was to take my place on the other expedition. Lucky for me! Selous was shot by a German sniper as he rode in front of his men. Mercifully he was shot in the neck and died instantly - a very gallant gentleman, who had guided the Pioneer column into Rhodesia, and, although well over sixty, was in the field again.

Above: Major Philip Jacobus Pretorius and below, his book 'Jungle Man'

Captain Selous, of the 25th Royal Fusiliers, who had hunted big game north of the Zambesi even before my time, was buried close to where he fell in the African wilds, where the lions serenade the spirit of a great shikaree. I think he would have liked to die, in the face of the enemy, and to be buried where he sleeps his long rest in the remote jungle-land.

An Indian Army view of Selous was made by Captain F A Archdale of the 130th Baluchis:

Selous was killed in this action: he was wounded in the knee quite early on, but refused to give up, but an hour or so later he walked into a Jerry machine gun at Beho-Beho where we buried him. He was a great man Daddy Chai (the name the sepoys gave him as he liked to drink tea), and we missed him very much. Our Pathans recognized him as a man of adventure and a perfect shot which appealed to them more than anything. Their sorrow at his death was very genuine.

Another account of the circumstances surrounding the Behobeho action was given by General Smuts to J G Millais who wrote Selous' biography:

"Our force moved out from Kissaki early on the morning of January 4th 1917, with the object of attacking and surrounding a considerable number of German troops which was encamped along the low hills east of Beho-Beho (Sugar Mountain) northeast of the road that led from Kissaki southeast to the Rufigi River, distant some 13 miles from the enemy's position. The low hills occupied by the Germans were densely covered with thorn-bush and the visibility to the west was not good. Nevertheless they soon realized the danger of their position when they detected a circling movement on the part of the 25th Royal Fusiliers, which had been detailed to stop them on the road leading southeast, the only road, in fact, by which they could retreat. They must have retired early, for their forces came to this point at the exact moment when the leading company of Fusiliers, under Captain Selous, reached the same point. Heavy firing on both sides then commenced, and Selous at once deployed his company, attacked the Germans, which greatly outnumbered him, and drove them back into the bush. It was at this moment that Selous was struck dead by a shot in the head. The Germans retreated in the dense bush again, and the Fusiliers failed to come to close quarters, or the enemy then made a circuit through the bush and reached the road lower down, eventually crossing the Rufiji."

Millais goes on to say:

When he came to the road, Selous and his company met the German advanced guard, which probably outnumbered his force five to one. He had, however, received his orders to prevent, if possible, the enemy from reaching the road and retreating, so he immediately extended his company and himself went forward to reconnoiter. It was whilst using his glasses (binoculars) to ascertain the position of the enemy's advance guard that Selous received a bullet in his head and was killed instantly.

Selous had just returned from convalescent leave in England and it appears likely that in the brigade advance he was tasked with commanding the leading company of Fusiliers and guiding them to the road running past Behobeho. Second Lieutenant E J Dutch took over command of Selous' company but was immediately mortally wounded.

The fight for the Rufiji Crossing at Kibambawe

Captain Ernst Otto commanded the German troops facing the advance of the two easternmost British columns, and his troops were the Nos 1, 3, 9, 23 and 24 Field Companies. Von Chappuis' detachment had re-joined Otto's command before the Beho-Beho action. After he had disengaged at Beho-Beho, Otto marched his men south past Lake Tagalala to Kibambawe, where he crossed the Rufiji on the night of 4 January 1917. Otto's troops then dismantled the roadway on the bridge that crossed the river at that point, leaving only the wooden piers that were driven into the river bed. So far the German casualties had been 1 European and 11 Askari killed, 1 European and 12 Askari wounded and 6 Europeans and 21 Askari missing.

When reports arrived of the successful crossing of the Rufiji by the westernmost British column, Otto sent No 9 Field Company and Wangoni Company to Mkindu and No 1 Field Company to Mkalinzo. The remaining companies defended the Kibambawe crossing. Otto did try to telegraph Colonel Paul von Lettow Vorbeck's Schutztruppe headquarters to ascertain whether he should fight on the Rufiji or withdraw further south to Utunge, but the German headquarters was on the move and communications failed. Otto stayed on the Rufiji.

On 5 January, 1st East African Brigade followed up Otto's withdrawal with the 130th Baluchis leading. On reaching the north bank of the Rufiji, a prominent hill above the river was found entrenched but unoccupied by the enemy. The brigade occupied the feature, naming it Observation Hill because of the wide view that could be obtained from its slopes. The width of the river below Observation Hill varied from 350 to 650 metres and the depth made it unfordable. Hippopotami and crocodiles in the water compounded the British difficulties. A ridge line south of the bridge site gave the German machine gunners a good field of fire onto any British attempts to repair the bridge or to cross the river at that point.

But further west the German-occupied ridge was more distant from the river and a suitable point was found for a crossing at a distance of around two kilometers from the bridge. Here the river was only 350 metres wide. General Smuts' headquarters had ordered that a crossing was to take place as soon as possible. Two Royal Navy ships' lifeboats had been carried and hauled through the bush by relays of exhausted porters, but when the lifeboats arrived at the Rufiji it was found that the oars had not been packed in the boats. This left seven small Berthon boats available, each capable of carrying only three men including the crewman. These boats had been designed by a British clergyman in India, the Reverend E L Berthon, and they had been introduced into the Indian Army for operations on the North West Frontier.

The 30th Punjabis were ordered to cross the river and a reconnaissance party of two officers and four sepoys under Captain J A Pottinger MC was rowed across; bayonets had to be used to dissuade hippos from getting too close to the frail boats. When he had selected a suitable concealed defensive position, Pottinger ordered the remainder of his ‘B' Company (Punjabi Musulmans) to cross. By dawn the company with two machine guns was over the river and concealed in thick beds of reeds. Throughout 6 January the Germans were unaware of the small British bridgehead on the southern bank. During this day the sepoys lay still, suffering from pangs of thirst and hunger. That night the remainder of the Punjabis and one company of the Baluchis crossed into the bridgehead and entrenched there under the command of the Punjabis' commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Ward.

After first light on 7 January Otto's men observed the British position on the south bank and opened fire on it. Captain W K B Wilson, commanding ‘D' Company (Sikhs) of the Punjabis, was ordered to advance eastwards parallel to the river. This advance was stopped by a German counter attack. ‘C' Company (Dogras) of the Punjabis under Second Lieutenant C P Clarke advanced southeast to secure ‘D' Company's right flank. Pottinger was then ordered to advance with ‘B' Company and attack the enemy in order to relieve the pressure on ‘D' Company. Ward then sent his ‘A' Company (Sikhs) under Major A H G Thomson to hold the line to the right of ‘D' Company. The 30th Punjabis was now totally committed into the firing line where two separate heavy actions were being fought, with ‘D' and ‘A' Companies on the left and ‘B' and ‘C' Companies on the right. Ward had used up his reserves and his only remaining sub-unit, the Baluchi company, was manning the bridgehead trenches. Meanwhile effective German machine gun fire and shrapnel shells from the Colonial Gun riddled four of the Berthon boats and halted river crossings. Shepherd's brigade responded from the north bank with machine gun and artillery fire, but direct fire support to the Punjabis was not possible because of the thick vegetation that concealed the battlefield.

The Punjabis began to be overwhelmed by German counter-attacks and battalion battle procedures faded away as orders failed to arrive at the firing line and reports from the companies failed to reach Ward's headquarters. Thomson was severely wounded and ordered his men to leave him on the battlefield. The unwounded company commanders fought their own withdrawal actions back through 2.5-metre high beds of reeds before the line was stabilized again. Pottinger was the decisive leader on the ground throughout the battle and he now supervised the defence of the British line.

But by 1500 hours the Punjabis were running out of ammunition and German machine guns were still controlling the river. Volunteers were called for from the 130th Baluchis to row ammunition across the river in the remaining boats; four men responded, Havildar Saraf Faraz teaming up with Lance Naik Fazl Ilahi, and Havildar Ghulam Mahomed being accompanied by Private Karum Ilahi. Both boats and their vital cargo got across although Saraf Faraz was shot dead leaving Fazl Ilahi to row the boat single-handed. This critical re-supply put fresh life into Ward's defence and the Punjabis held their ground until firing stopped at last light.

British consolidation of the south bank

That night, 7 January, the remainder of the 130th Baluchis plus a company of 3rd Kashmiris were ferried across the river. This placed 600 men and 10 machine guns on the south bank, and, whilst this force could and did repel another German attack, it could not advance whilst German machine gunners were sited on the ridge to the south. Sheppard had achieved his aim and had crossed the Rufiji, but he did not order a further aggressive action until more of his guns had been laboriously brought up to the north bank. On 11 January the 25th Royal Fusiliers was withdrawn from the front, too debilitated by disease and hunger to remain on operational duty. 1st East African Brigade now needed reinforcement before it could fight decisive actions on its own. Sheppard had already lost the 2nd Rhodesia Regiment and 2nd Kashmir Rifles through debilitation.

British probes on 18 and 19 January discovered that Otto had pulled back most of his companies as von Lettow made another tactical withdrawal and re-grouped his forces for the oncoming rainy season. The rains fell heavily and the Selous grave site at Beho-Beho Chogowali was covered by two metres of water. General Smuts was out of the theatre, having handed over command to General Reginald Hoskins before sailing for other duties in London, where the food supply was not so critical.

Casualties and awards for the Rufiji crossing

During the heavy fighting on the south bank of the Rufiji the 30th Punjabis lost their Machine Gun Officer Second Lieutenant William Charles Robinson, Subadar Allah Dittah, Jemadar Pahlwan Khan and 14 sepoys killed in action. Major A H G Thomson, an Indian officer and 44 sepoys were wounded, and 17 sepoys were missing. Subadar Thakar Singh had gone out in the night to recover Thomson.

Otto had deployed 1st Schutzen Company, Nos 3 and 24 Field Companies and Wangoni Company against the Punjabis, and his reported casualties were 2 Europeans and 7 Askari killed, and 5 Europeans and 30 Askari wounded.

Captain John Ashton Pottinger received an immediate Bar to his Military Cross with the citation:

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. By his skilful dispositions he concealed the presence of his company from the enemy. Later, he took a prominent part in the fighting, and handled his company with marked courage and efficiency under the most difficult circumstances.

Pottinger had won his Military Cross whilst attached to the 29th Punjabis in the Tsavo Valley in British East Africa in 1914. His retort to Lieutenant Colonel Ward on receiving his Bar was:

"Thank you Sir, but you might have made it a DSO this time."

After the strenuous and courageous efforts that he displayed whilst holding his unit together during the battle, Pottinger probably was not joking.

4291 Lance Naik Fazal Ilahi, 130th Baluchis, was awarded an Indian Order of Merit, 2nd Class. Jemadar Allah Dittah received a similar award but posthumously.

Jemadar Hakam Singh, Subadar Thakar Singh, 3911 Havildar Lall Singh, and Lance Naiks Ismail Khan and 4060 Gulaba, all of the 30th Punjabis, received the Indian Distinguished Service Medal.

Six months later Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Ward and Major Alexander Henry Gouger Thomson, 30th Punjabis, were both awarded the Distinguished Service Order.

Commemorations

Frederick Courtenay Selous lies where he was first buried in what has now become the Selous Game Reserve. William Charles Robinson lies in Morogoro Commonwealth War Graves Commission Cemetery (CWGC) and the dead Royal Fusiliers are buried in Dar Es Salaam (Upanga Road) CWGC Cemetery, Tanzania. The dead Indian officers and sepoys are commemorated on the CWGC British and Indian Memorial in Nairobi South Cemetery, Kenya. The dead African porters are unlisted but were commemorated by excellent bronze statues in Nairobi and Mombasa, Kenya. Sadly the Mombasa memorial has recently been desecrated by metal thieves.

Article, maps and images contributed by Harry Fecitt MBE TD.

Related articles on the WFA's website:

The Advance Beyond Kilimanjaro German East Africa (now Tanzania), March 1916

The Battle for Latema-Reata Nek, British East Africa, 11 - 12 March 1916

Indian Volunteers in the Great War East African Campaign

The King's African Rifles at Kibata, German East Africa December 1916 to January 1917

Out on a Limb - the road through Tunduru: German East Africa, May to November 1917

Medo and Mbalama Hill, Portuguese East Africa, 12 - 24 April 1918

Sources:

- War Diary of the 25th Battalion The Royal Fusiliers (Frontiersmen).

- 30th Punjabis by James Lawford (Osprey Men-At-Arms Series).

- The Archdale Papers in the Liddle Collection, Leeds University, UK.

- Draft Chapter XIV of the Official History, Military Operations East Africa, Part II (CAB 44/6).

- The Forgotten Front. The East African Campaign 1914-1918 by Ross Anderson.

- Three Years of War in East Africa by Captain Angus Buchanan MC.

- Die Operationen in Ostafrika by Ludwig Boell.

- Some Notes on Tactics in the East African Campaign an article by Brigadier General S.H. Sheppard CB, CMG, DSO in the April 1919 issue of The Journal of the United Service Institution of India.

- Life of Frederick Courtenay Selous DSOby J.G. Millais.

- Reward of Valour. The Indian Order of Merit 1914-1918 by Peter Duckers.

- The Indian Distinguished Service Medal by Rana Chhina.

- The Cross of Sacrifice, Volume I compiled by S.D. & D.B. Jarvis.

- The London Gazette, Medal Index Cards and Commonwealth War Graves Commission records.