Deep water discovery: ProjectXplore locates HMS ‘Nottingham’

- Home

- Latest News

- 2025

- July 2025

- Deep water discovery: ProjectXplore locates HMS ‘Nottingham’

After more than a century beneath the North Sea, HMS Nottingham—the last missing British cruiser of the First World War—has finally been located. ProjectXplore, a community-led shipwreck exploration initiative, announced the discovery of the Birmingham-class light cruiser this month, bringing to a close one of the Royal Navy's longest-standing mysteries.

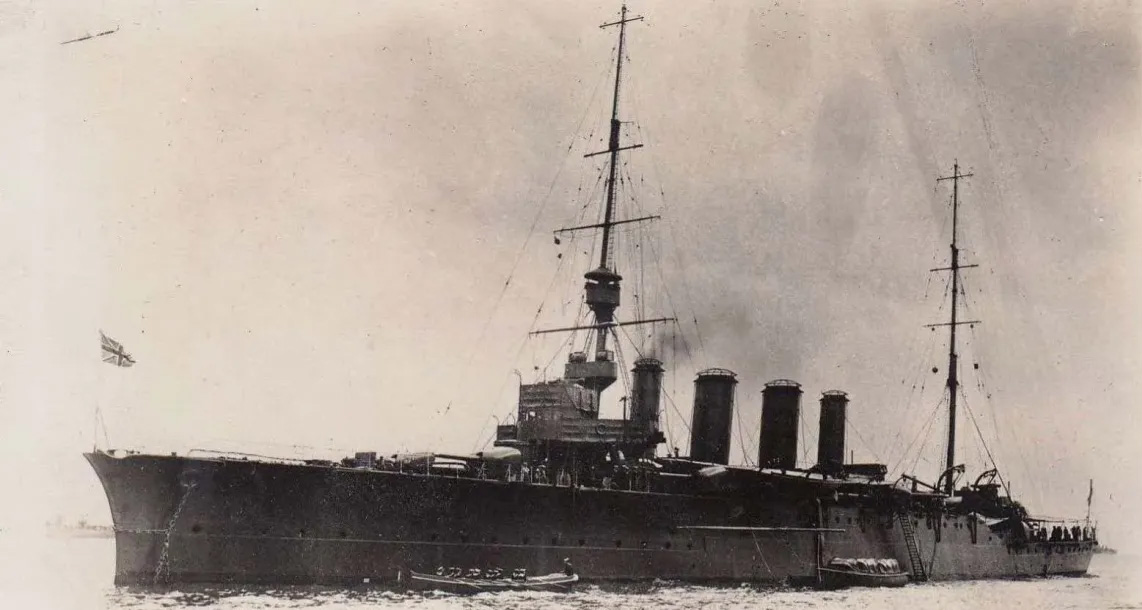

HMS Nottingham was no ordinary warship. Completed at Pembroke Dockyard on 1 April 1914, she represented the pinnacle of pre-war cruiser design—one of the celebrated "Towns" that naval historians consider arguably the finest cruisers of the First World War. Her 5,440-ton displacement, distinctive thin-thick-thick-thin funnel arrangement, and main armament of nine 6-inch guns made her a formidable scout for the Grand Fleet.

Her service record reads like a roll-call of the war's major naval engagements. At Heligoland Bight in August 1914, she was among the first British ships to taste victory in the North Sea. She fought at Dogger Bank in January 1915, and culminated her career at Jutland on 31 May 1916, where alongside Birmingham, Southampton, and Dublin, she engaged in fierce close-quarters combat with German light cruisers. As the official history records, during those "deadly minutes" at Jutland, "the Nottingham and Birmingham had been pouring in rapid fire at point-blank practically undisturbed."

Her final action: 19 August 1916

The circumstances of Nottingham's loss on 19 August 1916 epitomise both the tactical innovation and tragic cost of naval warfare. The action began as Admiral Scheer's ambitious plan for the High Seas Fleet's final major offensive against the English coast—an operation that would employ submarines in close coordination with the battle fleet for the first time.

As the Grand Fleet raced south to intercept, Nottingham formed part of the 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron screening ahead of Beatty's battlecruisers. Unknown to the British, a line of German submarines lay in wait. At approximately 0530 hours, Dublin's navigator spotted what he took to be a small fishing vessel—in reality, U-52 manoeuvring into attack position.

The submarine's assault was methodical and devastating. U-52's war diary, translated by the ProjectXplore team, records firing two torpedoes from her stern tubes, achieving direct hits forward. Twenty-four minutes later, as Captain C.B. Miller worked desperately to save his ship by shoring up watertight bulkheads, U-52 struck again with a torpedo amidships. At 0710 hours, HMS Nottingham slipped beneath the waves, taking 38 of her crew with her.

The rescue operation that followed demonstrated both courage and the deadly cat-and-mouse nature of submarine warfare. Dublin, Penn, and Oracle raced to save survivors whilst U-52 continued her attacks, forcing the rescue vessels to "exercise considerable skill and coolness" to evade further torpedoes. In a poignant detail, U-52's crew later recovered one of Nottingham's lifeboats, finding not only a lifebuoy marked "HMS Nottingham" but also the ship's cat.

The discovery

ProjectXplore's systematic approach to locating Nottingham began with eight months of archival research across the National Archives, Imperial War Museums, and German naval records. The team, led by Dan McMullen and Leo Fielding, meticulously plotted estimated positions from both British and German sources, ultimately discovering that U-52's navigator had been remarkably accurate in his position reporting.

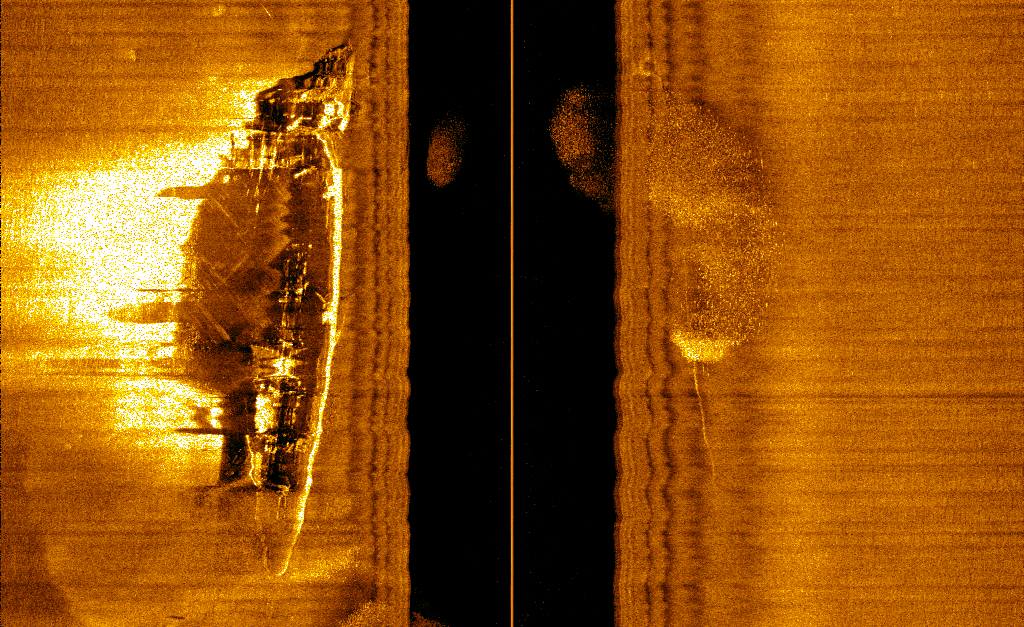

On 22 April 2025, using a C-MAX CM2 side-scan sonar towed from MV Jacob George, the team detected "the faint but unmistakable straight, narrow lines of the hull of a warship" approximately 60 miles offshore. The wreck's dimensions—139 metres long by 15 metres beam—matched Nottingham exactly.

The evidence for identification is overwhelming. ProjectXplore divers documented the ship's name "NOTTINGHAM" embossed across her stern, adjacent to a porthole looking into the Captain's day cabin. All nine 6-inch guns remain in position: two on the forecastle side-by-side (the distinctive Birmingham-class arrangement), two amidships between the foremast and first funnel, two between the third and fourth funnels, two aft of the mainmast, and one on the centreline at the stern.

The wreck's condition closely matches historical accounts of her loss. She lies with a 45-degree list to port, exactly as reported by survivors, with clear torpedo damage forward of the bridge on the port side—precisely where U-52's torpedoes struck between watertight bulkheads 28 and 40. Her distinctive four funnels, anchor equipment comprising three hawse pipes with kedge anchors, and even wooden decking amidships remain remarkably preserved.

HMS Nottingham today represents the best-preserved "Town"-class cruiser in existence. Whilst her sister ships were broken up in the inter-war years, she rests in 82 metres of water as a testament to both her robust construction and the relative depth and undisturbed nature of her final resting place. ProjectXplore found unused ammunition stowed near the guns, the engine revolution telegraph still in position on her fallen bridge, and Royal Navy crown emblems clearly visible on port-side plating.

Beyond her historical significance, HMS Nottingham remains the final resting place of 38 sailors, many barely out of their teens. The casualties included Stoker 2nd Class Ernest William Woolcock, just 18 years old, and Stoker 1st Class William Thomas Perring, aged 19.

The discovery of HMS Nottingham closes a significant chapter in First World War naval history. As ProjectXplore note in their report, until her discovery, she was ‘the last missing Royal Navy cruiser of the First World War.’

The Royal Navy has been notified of the discovery, ensuring that appropriate protocols for this war grave are followed.