From plumber to pioneer: a Kiwi soldier’s insight into a scientific revolution

- Home

- Latest News

- 2025

- July 2025

- From plumber to pioneer: a Kiwi soldier’s insight into a scientific revolution

A small, unassuming journal discovered in a hospice sorting facility has cast new light on the remarkable foresight of a New Zealand sapper during the First World War and his documentation of a technology that would revolutionise public health.

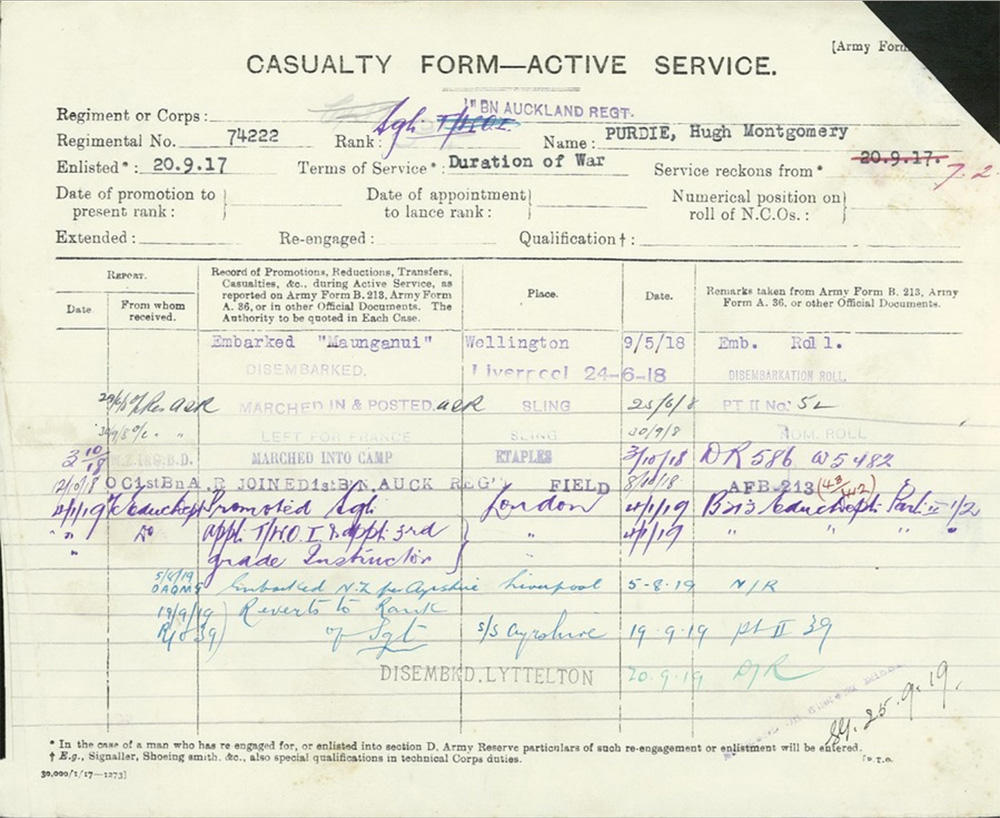

In a report from July 2025, the Whanganui Chronicle detailed the journey of a handwritten notebook from a Hospice Mid-Northland sorting shed in Kerikeri to its new home at the National Army Museum Te Mata Toa in Waiouru. The journal belonged to Hugh Montgomery Purdie, an Auckland plumber who enlisted in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) on 20 September 1917, with service reckoned from 7 February 1918.

According to his military service record, Purdie was born in Auckland on 10 August 1894. At the time of his enlistment, he was a 23-year-old Presbyterian with fair complexion, blue eyes, and brown hair, standing five feet, five and a half inches tall. He embarked from Wellington aboard the Maunganui on 9th May 1918, arriving in Liverpool on 24th June 1918. He served in France from September 1918 with the Auckland Infantry Regiment.

It was during his time in Europe, likely in France, that Purdie, with his professional plumber's understanding of sanitation, observed and meticulously recorded a groundbreaking method of water sterilisation. As Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga relates, his journal contains detailed notes on a process using ultraviolet (UV) light generated by large military searchlights to purify water.

Purdie documented rigorous tests on water from the River Seine, which had been intentionally contaminated. He wrote:

The process was subjected to severe tests. The water to be treated was drawn from the Seine below Paris and was further contaminated with germs of cholera, diphtheria – indeed, every effort was made to make the water as poisonous as possible.

The results were unequivocal.

The germ-contaminated water was then drawn off in the usual manner, being induced to flow over the lamp, and upon withdrawal was found to be absolutely sterile – all contagious germs having been completely destroyed as a result of exposure to the ultraviolet rays.

What makes Purdie's account so extraordinary is his vision for the technology's future applications. Heritage New Zealand Northland Manager, Bill Edwards, told the Whanganui Chronicle:

What’s also impressive is Purdie’s ability to see the potential for this new technology to improve the lives of many, suggesting that it would only take a small dynamo to feed the lamps with the necessary current.

This was decades before UV sterilisation became a scientifically proven and widely adopted method for treating urban water supplies in the 1930s.

After the Armistice on 11th November 1918, Purdie's career took an educational turn. His service record shows that on 4 January 1919, he was appointed to the NZ Educational and Vocational Training Scheme as an instructor. He was promoted to Sergeant a month later. It is highly probable, as Edwards suggests, that the detailed notes in his journal were intended for use in his new teaching role.

Sergeant Hugh Purdie was finally discharged on 23rd October 1919, having served a total of one year and 259 days. He returned to New Zealand, disembarking at Lyttelton on 20th September 1919.

Heritage New Zealand is still seeking more information about Purdie's life after the war, including his service in the RNZAF during World War II and details about his family. Anyone with information is encouraged to come forward to help complete the story of this forward-thinking soldier.