From goal line to firing line: Robert ‘Pom Pom’ Whiting

- Home

- Latest News

- 2025

- November 2025

- From goal line to firing line: Robert ‘Pom Pom’ Whiting

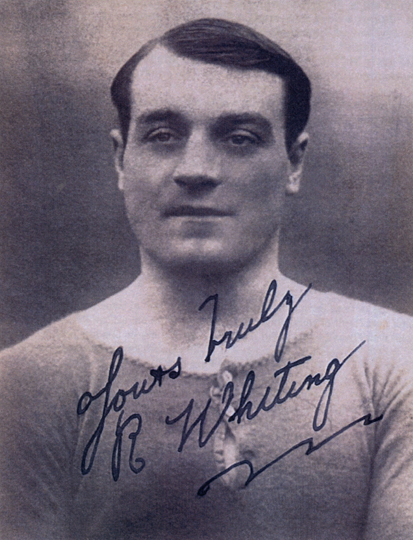

In the collective memory of Brighton and Hove Albion, few names from the pre-First World War era resonate as strongly as Robert ‘Pom Pom’ Whiting. A goalkeeper of significant repute, Whiting’s career trajectory was interrupted by the outbreak of the Great War – a conflict that would see him transition from sporting hero to soldier, then to accused deserter, and finally to a fallen serviceman whose reputation required posthumous defence.

Whiting’s story recently featured on BBC Radio Secret Sussex, with contributions from Peter Daniel of Westminster Archives and Peter Burgess (Whiting’s nephew).

Born in London, Whiting played for West Ham United and Chelsea before transferring to Brighton and Hove Albion in the summer of 1908. It was on the south coast that he cemented his legacy. He was a formidable physical presence between the posts, but it was his kicking ability that earned him his moniker. His distribution was so powerful it was compared to the range and force of the ‘Pom-Pom’ gun, the QF (Quick Firing) 1-pounder gun used in the South African War.

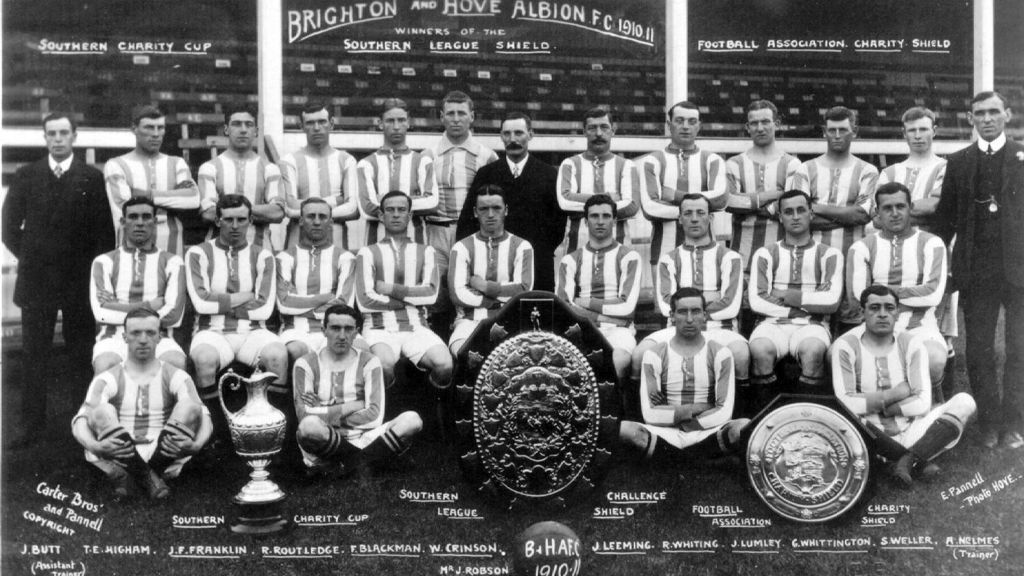

Whiting was integral to the club’s greatest early success. In 1910, he was part of the Brighton side that won the Charity Shield, defeating the Football League champions Aston Villa to be crowned the unofficial ‘Champions of All England’. For seven seasons, he was a fixture at the Goldstone Ground, living just minutes away on Westbourne Street in Hove.

When war broke out in 1914, professional football continued briefly, drawing ire from establishment figures such as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle who viewed the continuation of sport as unpatriotic. Under pressure from the media – specifically outlets like the Daily Sketch which urged athletes to open a ‘new front’ – the football authorities responded.

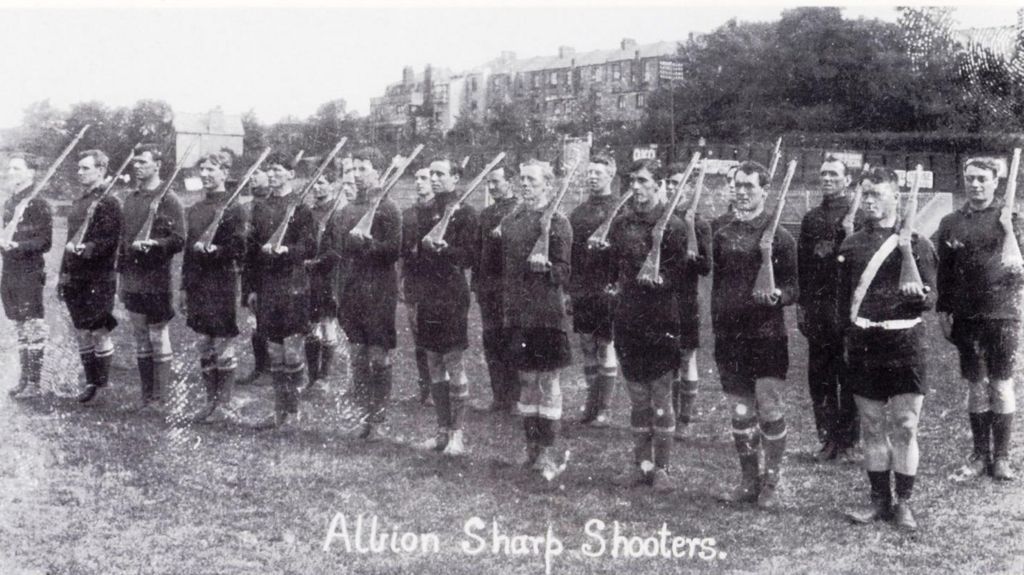

A recruitment drive led to the formation of the 17th Service Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment, widely known as the Football Battalion. Whiting, described as a consummate team man, enlisted alongside several Brighton teammates in early 1915. The promise sold to these men was that they could train as soldiers during the week and fulfil their sporting fixtures on Saturdays. By late 1915, however, the realities of the Western Front had superseded the football pitch.

After a year of infantry training and initial tours of the trenches, Whiting’s health deteriorated. While serving in the firing line, he contracted severe scabies and was evacuated back to England for treatment at the Eastern Military Hospital, located in the Brighton, Hove and Sussex Sixth Form College (BHASVIC) building on Dyke Road.

It was during this convalescence that Whiting’s military record was tarnished. With his wife Nelly pregnant with their third child, Whiting failed to report for duty upon his recovery. He went absent without leave (AWOL) for 133 days, effectively hiding in plain sight with his family.

He was arrested in October 1916 and court-martialled for desertion. In the earlier stages of the war, such an offence might have resulted in a death sentence. However, by late 1916, the British Army had suffered catastrophic losses during the Somme offensive. The military could not afford to waste experienced soldiers. General Hubert Gough intervened, commuting the sentence. Whiting was stripped of his rank – demoted from Lance Sergeant to Private – and sentenced to hard labour, which was suspended so he could be returned immediately to the front.

Whiting returned to France in time for the Arras offensive in April 1917. On 28 April, the 17th Middlesex took part in a chaotic and costly assault on German lines at Oppy Wood. The battalion was decimated; reports suggest only one officer and 41 men returned unscathed.

Private Robert Whiting, aged 34, was among the 462 men killed that day. Crucially, eyewitness accounts and letters from his commanding officer, Second Lieutenant Howard, confirmed that Whiting did not die cowering. He was killed by shellfire while in No Man’s Land, reportedly attempting to provide aid to wounded comrades.

Despite his death in action, Whiting’s family in Brighton faced a second ordeal. Malicious rumours circulated locally that ‘Pom Pom’ had been executed by firing squad for cowardice, conflating his previous court martial for desertion with his death.

These rumours caused immense distress to his widow, Nelly, and their children. It took a concerted effort to clear his name. In 1919, the Sussex Daily News published a definitive rebuttal of the gossip, citing official military documents and the testimony of officers who witnessed his final moments. They confirmed he had died "doing his duty both well and nobly".

Today, Robert Whiting is commemorated on the Arras Memorial in France, having no known grave. In Hove, his name appears on the war memorial plaques at the town library, listed simply as Whiting, R.

Acknowledgments

This article is based on the BBC Radio feature Secret Sussex, and the accompanying BBC News report.

Further reading

- Bob Whiting of Brighton, photohistory-sussex.co.uk

- The Football Battalions, footballandthefirstworldwar.org