Newly discovered letters reveal Rudyard Kipling’s search for his son

- Home

- Latest News

- 2025

- October 2025

- Newly discovered letters reveal Rudyard Kipling’s search for his son

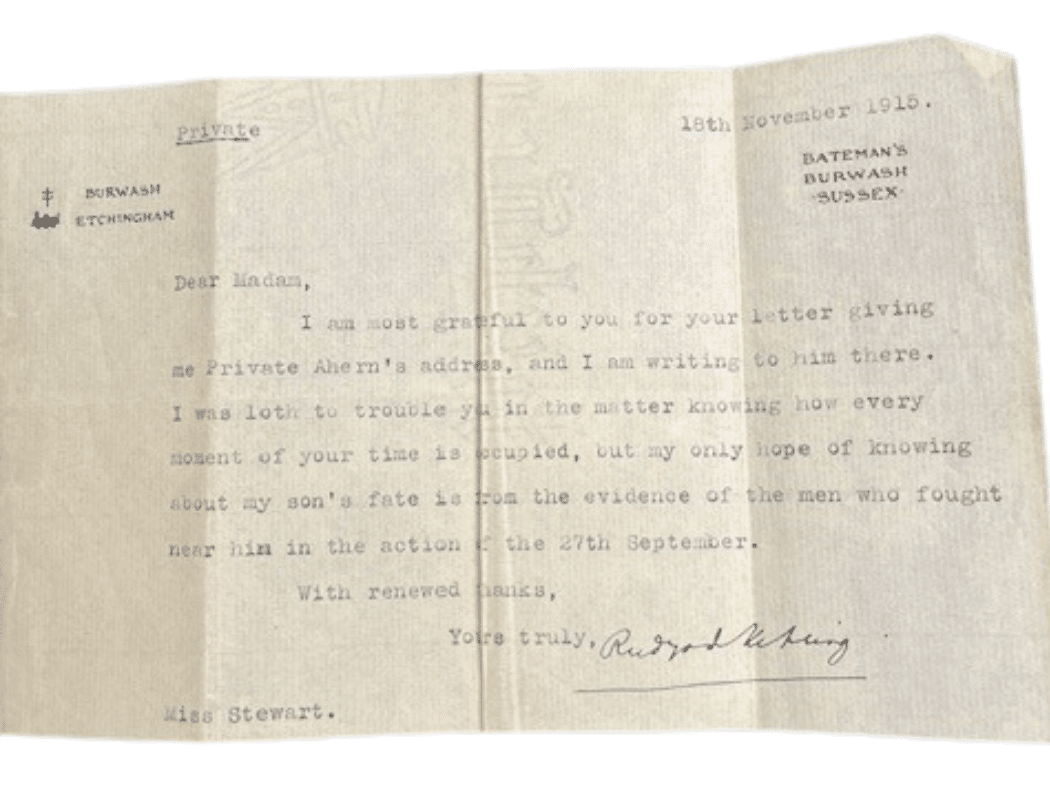

Recently unearthed letters from 1915 have cast a fresh light on author Rudyard Kipling's desperate search for his son, John, who went missing on the Western Front during the First World War.

The correspondence, auctioned on 10 October, reveals the personal anguish of the celebrated writer as he sought information about his son's fate. In one letter, Kipling wrote, “My only hope about knowing about my son's fate is from the evidence of the men who fought near him on the action of the 27th September.”

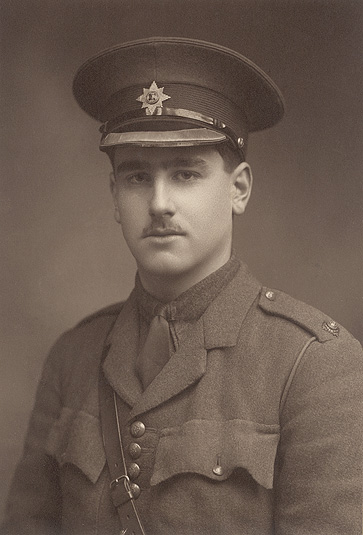

John, known as Jack to his family, was the only son of Rudyard and Caroline Kipling. An ardent patriot, Rudyard Kipling was a vocal supporter of the war effort, contributing his writing to propaganda and recruitment campaigns. He used his influence to secure his son a commission as a second lieutenant in the Irish Guards, despite John having been initially rejected for military service due to poor eyesight.

Just two days before his seventeenth birthday in August 1914, John Kipling was commissioned into the 2nd Battalion, Irish Guards. He was sent to France in August 1915, where his father was also visiting as a war correspondent.

On 27 September 1915, during the third day of the Battle of Loos in northern France, Second Lieutenant John Kipling was reported “wounded and missing” as his battalion advanced towards Chalk Pit Wood. He was 18 years old. The battle was the largest British offensive of the war to that point and resulted in tens of thousands of casualties.

In the newly discovered letters, addressed to the matron of the City of London Military Hospital, Kipling expressed his anxiety. “So far we can get no report from Germany of his being a prisoner there, or any report from Belgium of his being in hospital there, and we are anxious to get the evidence of the men who were wounded in the same action,” he wrote.

The loss had a profound effect on Kipling. He became involved with the Imperial War Graves Commission (now the Commonwealth War Graves Commission) and is credited with suggesting the phrase ‘Known unto God’ for the headstones of unidentified soldiers. He also wrote a history of the Irish Guards, a project he undertook because of his son's death.

Rudyard Kipling died in 1936 without ever knowing what happened to his son. It was not until 1992 that the grave of an unknown Irish Guards lieutenant in St Mary’s Advanced Dressing Station Cemetery at Haisnes, near Loos, was identified as that of John Kipling by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, although there has been some debate over the years regarding the identification.

Read more:

For detail on the identification of John Kipling’s grave, see the extensive article by Graham Parker and Joanna Legg in Stand To! Number 105, available online to members in the Searchable Magazine Archive.