Ep. 105 – Researching British Officers in WW1 – Prof. Michael Durey

- Home

- The Latest WWI Podcast

- Ep. 105 – Researching British Officers in WW1 – Prof. Michael Durey

Emeritus Professor Michael Durey, from Murdoch University, Perth, Western Australia, talks about his background and interest in history and his current research project which explores the lives of British officers killed on the Western Front during the Great War.

Born in Bethnal Green, Blackheath, Michael Davey took his first degree at York University where he stayed to completed his DPhil in 1975. He worked there for 5 years until the opportunity arose to move to Murdoch University, Perth, Western Australia where he has lived ever since, retiring in 2015.

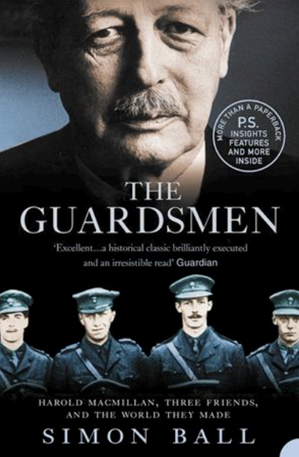

It was having read Simon Ball’s ‘The Guardsmen’ about the lives of Harold Macmillan, Oliver Lyttlejohn and Harry Crookshank that his interest in the ‘officer class’ arose. Researching just one day in the war, 1 September 1916 he learnt that 400 officers were killed on that day alone. Broadly covering the themes of ‘Life, Death and Remembrance’ he applied for a research grant to look at three interwoven themes: the myth of ‘six weeks’, the meaning and practicalities of what was meant to become one of the ‘missing’ and the remembrance as shown in stained glass, particularly that remembering Leonard Waugh. Duly granted Michael set about his research which he shares here with Tom Thorpe.

Six Weeks

The simplest answer is that there is no truth in the idea that the life of an officer on the Western Front was only six weeks. However, it is possible to understand how this idea came about. There was a perception that men didn’t last long. Robert Graves, writing 40 years after events, suggest three months was the average before an officer at least become a casualty. Notably, the RFC pilot Cecil Lewis put a pilot’s life span down to only three weeks. Michael Durey looked closely at 12 battalions on the Somme. The casualty rate was a little under 49%. Under 17% were fatal. And of cause for over 50% there were no casualties at all. For casualties, on average they could go nearly six weeks without injury or death.

The Missing

Our idea of ‘the missing’ is based on memorials to the missing; it meant different things at different times to be ‘missing’ and its meaning changed after the war. This brings into question how casualties were reported and how families were told. A man might be ‘missing’ but in hospital, or a prisoner of war.

Stained Glass in Church Memorials to those who died during the First World War

This curiosity concerns a memorial to Leonard Waugh what was destroyed by a VI bomb and rededicated in the 1950s. Leonard composed the lines ‘We win or die who wear the rose of Lancaster’ - after Rudyard Kipling the most quoted line on CWGC gravestones.

Find out more on British Army Officers in the Great War