Ep. 166 – Washington in the Great War – Peter Welsh

- Home

- The Latest WWI Podcast

- Ep. 166 – Washington in the Great War – Peter Welsh

Peter Welsh talks about his research into the community of Washington during the Great War.

Dr Tom Thorpe (TT) : Welcome to ‘Mentioned in Dispatches’ the podcast from The Western Front association with me. Dr. Tom Thorpe. The WFA is the UK's largest Great War History Society. We are dedicated to furthering understanding of the Great War and have over 60 branches worldwide. For more information visit our website at TheWesternFrontAssociation.com.

It is the 22nd of June 2020 and this is Episode 166.

On today's podcast I talked to Peter Welsh who has been researching the community, ‘Washington in the Great War’. I spoke to Peter Welsh from his home in Washington.

TT: Hi Peter, welcome to the ‘Mentioned in Dispatches’ podcast. Could you start by telling us about yourself and how you became interested in the Great War.

Peter Welsh [PW]: As a child of the North East, if I was not going to be Jackie Milburn or Freddie Truman or The Range Rider - I did like reading history. My dad bought me history books as a present - and cricket books. I read the Great War, sorry, watched ‘The Great War’ on television in 1964. And obviously that had a big impact. I read AJP Taylor and his ‘War by Railway Timetable’ and then I became a history teacher and worked in Sunderland for 37 years in an inner-city comprehensive school. And then in about 1980 a girl called Ilona Taylor - the only Ilona I've ever met - walked into the classroom that I was working in and said, “Do you want these papers?” “What are they, Ilona?” “Oh, I don't know - something that my mam said she's going to throw away if you don't want them.”

It turned out to be a collection of papers and documents about how they built the South Hylton War Memorial, which was just close to the school. We used to use those in history lessons as primary sources and in a sense that re-lit an interest in the First World War and so we started taking kids to France.

TT: So before we get into detail, could you tell us where Washington is?

PW: I's between Newcastle, Sunderland and Durham. In 1964, it was created as one of the country's New Towns, Washington New Town, which meant that they put some factories in, an RCA Factory and various others. And of course, we've now got Nissan, In fact it's on the North-East coalfield. And originally it was ‘Washington CD’, as opposed to ‘DC’ - ‘Washington County Durham’. It's now part of whatever Tyne and Wear may be - it's a thing that's created, but I think people pay lip service to it and that's about all.

It's the place where in 1977 Jimmy Carter came and with James Callaghan planted, what turned out to be a dead tree, beside Washington Old Hall - because that was the ancestral home of the Wessington or Washington family. George Washington never lived there, but it was the ancestral home of that particular family dating back, I think, the first stone of the Old Hall was built in 1183. So it's Northeast - on the coalfield.

TT: So how did you become interested in Washington and the Great War?

PW: Well, after Ilona brought the papers in that I mentioned, before we started taking trips to France and this was in the days before the internet, so it was really difficult to find people who were from South Hylton. When my wife and I moved, when Margaret and I moved into Fatfield in the 1990s the memorial, the Fatfield War Memorial, or the Harraton War Memorial, was directly outside our front window on the Worm Hill, which local people will know, “Whist! lads haad yor gobs, An aa’ll tell you aall an aaful story” - the story of the Lambton Worm and the Lambton family.

Over two or three bottles of wine, perhaps it might have been … it was suggested that we should find out who the 102 names on the Harraton War Memorial were. I retired in 2005, and typical history teacher, I was ‘sad man in the bedroom with a computer’, which I was already starting to use - and a file of information about these fellows which gradually built up having discovered who most of them were we then moved on to the Usworth War Memorial and the Washington War Memorial . And our first exhibition was in the Art Centre at Washington in 2011.

TT: So, can you tell us what Washington was like in 1914? And what were the principal industries in the area? And what type of people lived in the vicinity?

PW: OK, Washington was basically four parishes in those days: there was Washington Parish with about 7,800 people and another 500 in Barmston. Usworth Parish had about 7,900 people in 1911 and then Harraton Parish, which - the main settlement in which is Fatfield - there were about 3,500 there. Basically, there was some farming - there were open fields. But the important thing, or the important things, were the pits: Glebe Colliery had about 700 men working there; ‘F’ Pit at Washington over 1,000; Usworth over 1,000; Harraton Colliery had over 1,000 men working above and below ground, and so did North Biddock. So you've got about 5,000 men and women working in the collieries there.

They lived in the terraces and the rows - imaginatively named New Row, Middle Row, North Row, South Row. Unlike Horton where they simply went for numbers: First Row, Second Row, Third Row. They did at least have some kind of name.

There was a Chemical Works - Newell's Chemical Works, which we are still reaping the benefits of with the chemicals there - it's now been built over - asbestos was involved. Cooks had iron works, there were brick works. But if you didn't work for any of those you probably worked for the Co-op or one or two little shops, and I think I should mention that the third Earl of Durham, Lord Lambton, or the Earl of Durham was the local chief land owner, I think, who lived in Lambton Castle - he had a significant impact on the area.

TT: When war broke out in 1914. What was the response to Kitchener's call for volunteers from the local community?

PW: I'm going to break into dialect here because according to the Chester-le-Street Chronicle, the question of the day was, “Wad thou gan, Jackie?” and Jackie's answer generally speaking was, “Aye, I’d gan, if you'd gan, Tommy! Would you go?” ”Yes, I'll go if you go.” So the fellows joined up together.

The Washington District Volunteer Record that was published in September 1914 listed 392 men. Some of them, Reservists, had only been in the DLI (or whatever) … who had signed up by the 8th of September. So there was an enthusiastic initial response that waned a little … Lord Lambton was somewhat controversial in saying, in November of 1914, that he’d like to see the Germans bomb Roker Park to encourage the men who were still going to watch football to join up. As a Newcastle supporter I was quite in sympathy with the idea that Roker Park should be bombed but not for the same reason as Lord Lambton.

I think that the level of enlistment can be gained from the fact that Washington produced about a 1,000 Tribute Medals at the end of the war Usworth Colliery, something like 700. And Harraton, which was remember about half the size, 410 men are in the Roll of Honour of whom of 102 were killed that’s a 25% death rate - which is quite staggering, and twice the national average. So, approximately, I think, about 2,500 men from Washington, and of course there were women as well who joined up who we might mention later. So about 2,500 men joined the forces from this area with a population of, what did we say about 18,000 war service.

TT: And what units did the men and women enlist in?

PW: I'm talking about the 383 who were killed now that we know about, of them, 95 were in the DLI - the Northumberland Fusiliers 59. And of course, there was the Tyneside Irish - the ‘Fighting Irish’, and there were thousands and thousands of Irish living in this area - Irish immigrants. And then there were the Tyneside Scots, who were ‘hard as hammers’, or according to them they were. And according to Dan Jackson, in his book, most of them joined up not because they had scotch - Scottish ancestry - but because they thought they might get to wear kilts. In fact, they were only allowed to wear trews - tartan trews, but trews all the same - the Green Howard's from Yorkshire. They've got the depot at Richmond - 59 in the Green Howard's, about 40 other Yorkshire Regiment, the KOYLIs. The East Yorkshires, The West Yorkshire Twenty-four fellas were in the artillery.

And, of course, most of our fellows started work with pit-ponies when they went down the pit at the age of 13, 14. Then 15 men were Royal Engineers - their skills from the collieries, I think we're very useful in the Royal Engineers. Some of them were remarkably skilled at the technical side of warfare. I think we had one in the RAF and five in the Navy. It was an area where the vast majority were working class men, so we had seven officers of the 383 who were killed - it gives an indication of the type of area it was.

TT: And do you know if those officers were promoted from the ranks? Or were they appointed because they went to the right school at the beginning of the war?

PW: An interesting story about one of them is a lad called John Dawson from Usworth who when he gave his address - this was a young man who'd gone up through the ranks, he described his address as ‘Pitt Cottages’ but with two ‘ts’. I wonder if he was trying to disguise the fact that it was the Pit Cottages. I can't believe he thought that Pit had two ts. I wondered if he was trying to indicate that actually it was William Pitt the Elder or the Younger that cottages that he came from, rather than coal miners’ cottages. But no, most of those fellows were sons of the vicar, a school teacher, you know, they were the kind of the professional classes in terms of the officers.

TT: And what other stories emerged from your research?

QQ: John Thomas Sandy's wife got a note from the Army saying that when he died he owed the Army three pence and she sent them three penny stamps and an army clerk has written that in the book of soldier’s effects - ‘From Mrs. Sandy of the Municipal Terrace, Washington - Three times 1d (pence) stamps’.

Joe Affleck - was the local scoutmaster. He took his 15 year old son Arthur to join up with him. I think he thought it was a bit of an adventure. Mrs. Affleck found out that people were getting killed in this war. And said to the Army shouldn't have her Arthur and so they sent him home. Joe was killed on the 1st of July 1916 along with 39 other blokes from Washington. And when the Usworth War Memorial was opened in 1922 the bugler who played the Last Post was Arthur Affleck, who of course by that time had had to join the Army because he was of the right age.

Robert Stephenson Gould - his body, we think, we're almost certain, was one of those discovered in 2001 in a mass grave. Near Arras, he went on the Arras Memorial as ‘missing’. He's now in Point du Jour Cemetery as an unknown soldier of the Lincolnshire Regiment but there's a piece in a book of archaeology about the Great War which shows you 34 men lying together with linked arms. So they've been buried and laid out, and it's almost certain that Robert Gould is one of them, but of course they don't do the DNA testing.

Billy Jonas - was a footballer from Clapton Orient, as it then was, Leyton Orient as it now is, and there's a memorial to him that people might have seen at Flers - from the Middlesex the Footballers Battalion.

And I'll finish with Nathan Marshall - Nathan was a - well, he never went before the Tribunal - was a conscientious objector, but I think it's quite clear that he was, judging by the friends that he had, one of whom was one of those ‘absolutist conchies’ - he would not do anything, but Nathan carried a stretcher and was killed in July 1916.

So a real range of stories, every one a tragedy.

I'll just want to mention one more. Willie Culine - Willie was ‘of no fixed abode’ when he joined the army. I suspected he’d never done anything that anybody ever told him and suddenly everybody was telling him what to do. His army record - there's a list of misdemeanors as long as your arm. When they were trying to contact Mrs. Culine - they had to get the Northumberland Police or the Newcastle Police involved to find her - she was living on the shore-ground at Byker in a caravan. And against where they put the list of relatives, against wife, Mrs. Culine wrote, ‘Willie wasn't married, thank God’. I think she meant there wasn't a woman in the world who could cope with him and neither could the British Army.

TT: So what happened on the Home Front in Washington during the war?

PW: There were blackberry collections and egg collections. There was an allotment at school and there were local allotments courtesy of Lord Lambton who offered some fairly poor land in fairly exorbitant prices, which the council turned their noses up at but would eventually an agreement was reached. Lady Lambton - Lady Anne Lambton, that's Lord Lambton’s sister - not his wife. His wife was in a mental institution. She ran the Lady Lambton Work Depots, so there was the local Sisterhood and the Work Parties, and the Welcome Home Funds, and the Saint John’s Ambulance classes - because everybody could do their bit. There were food orders - left, right and centre - saying what you could and couldn't do, and what you could and couldn't buy. This was a war for ‘freedom, democracy and the right to regulate people within an inch of their lives’.

There was a school strike in 1917 at Usworth, where the miners couldn't go on strike because they didn't have enough work anyway to feed the family, so they put their kids up to going on strike. That lasted a day and a half and then Durham County Council discovered that actually it could afford to pay for dinners for the school children. And so the strike was over but there was the usual accoutrements of a strike with kids shouting that the other kids who had gone to school were black legs and scallywags and there's some stone-throwing and that kind of thing.

There was lots of money raising to go on for the Belgian refugees and the Russian refugees and the DLI prisoners of war and other prisoners of war. Girls played football and the munitionettes came up to Lambton Castle to look after wounded soldiers. Each munitionette from Armstrong's Factory - the Newcastle giant munitions factory, they came down and they got a wounded soldier each and Lord Lambton gave them tea and said some charming things. Other women joined the WAAFs.

I'll finish in terms of the Home Front with - they give their kids strange names. There was a ‘Antwerp Colpitts’, an ‘Aisne Marsden’ - a ‘Neuve-Chapelle Isaac Smith’. I think “Neuve-Chapelle, your dinner's ready” must have been an interesting cry in the back streets of Washington, “Neuve-Chapelle come in pet, yor dinna’s ready”. There were a couple of Verduns. There’s an ‘Edith Loos Drummond’, whose father was shot in the head at Loos and subsequently died of his wounds - that's a burden to carry, named after the place where your father was killed. There was even an ‘Iris Alsace-Lorraine Wilson’.

TT: So when Armistice finally comes and the men returned home, what casualty levels are we talking about from the community? You've touched on this already. But have you done any sort of research on those who returned and what happened to them?

PW: All right. We have 383 names on our three local, on the three large local war memorials - that’s Usworth, Harraton and Washington Village some of those men are actually on two different memorials because they might live in one parish and work in another. There were some who clearly weren't on the memorials for whatever reason perhaps single men who'd been lodgers - there was nobody to speak up for them at the end of the war when they went around collecting the names. A couple of Quinns I think were killed. Of course during the 1920s, I'm currently going through the absent voters list and the Pension Records from the Western Front Pension Records and that's throwing light on those who died in their middling years during the 1920s. There was a steady supply, if you like, of men who had been damaged by the War and who were passing on well before their time, but of course the ‘Homes for Heroes’ didn't exist. Washington had, prior to the war, had plans for building council houses, but of course that all went in the end with the Depression of the 1920s or the depression in this area of the 1920s, so it was a time of great disruption. I don't think there were many ‘flappers’ in Washington.

TT: How does the community remember the service and sacrifice of its population that served in the Great War?

PW: Well, as I say, there are the three large memorials at Washington, Usworth and at Harraton, F Pit has a memorial the 60 odd names on. There's an Usworth Colliery Memorial, Top Club Memorial, Westwood Club Memorial … Fatfield School had 42 names - a couple of teachers and then boys who had attended that school. So all of these things exist. There were about 1,000 Tribute Medals made for Washington - I assume paid for by the colliery owners, who would be the only ones who had any real money. There were 666 Tribute Medals given out by Usworth colliery. Harraton, they did it slightly differently at Harraton and gave a gold watch to everybody who won the Military Medal or above and there were 18 of them.

And here's an interesting one. This lady, once in an exhibition at Beamish Museum said to me, “And did you know about the Café-Chantées?” I said, “the Café-Chantée? Whatever it is that?” It was a café in Fatfield after the First World War and the ‘chantée’ was a ‘singing’ Cafe. So the soldiers brought back the idea of Café-Chantée from France and so people would turn up there and sing away their troubles as best they could.

TT: I understand you've done quite a bit of outreach to the local community during the Centenary looking at Washington and the Great War. Can you tell us about some of the stuff you've been doing?

PW: Everything started with files, we then went on to exhibitions and we’ve done talks to all kinds of local groups: women's groups, church groups, Probus. We've done talks to them. We’ve made four films. The first one was ‘Wad thou gan?' Then took a bus load of 45 people and counted them out and counted them back in because there are of a certain age from Washington to Ypres and Wallencourt. We made a film about Washington men at the Somme. We made a film called ‘The Wear at War’ with Katie Adie in, and one or two other local stars, all of which was supported by the University of the Third Age because we are a U3A group and that enabled us to get grants from the Heritage Lottery Fund. There are links to all of those films. The four films are on YouTube and people can find the links to them on the website. They’re shown on ‘Made in Tyne and Wear Television or at least ‘Wad thou gan?’ is. So people will say to me sometimes in the street, “Well, I saw you on the telly last night. I heard you on the telly last night".

For the end of the war we got a local folk singing duo [Fool's Gold]. They performed them five times at Beamish Museum and at the local club and a couple of churches. We created a poppy walk with a hundred bronze resin poppies on houses or buildings where they used to work or live. A boy called Jordan Tough - what a great name and what a fantastic lad - started doing phone Apps in Year 9 at school. And by the time he left school, Jordan's a genius - and I'm not exaggerating - he has created this fantastic phone App. Where if you stand outside a house in Washington with a poppy on the front wall, you'll get a little video on your phone and all the stories, of all the men are on this phone App. That’s a staggering piece of work and achievement by that lad.

We've had the Pals Battalion. That's to say, my wife and her Pals U3A members and others. Some want to research some want to take photographs and want to knit some want to do talks and exhibitioons at Beamish Museum getting dressed up in the clothes of 1913-14. So the ‘Poppy Girls’, as we call them, started and we put poppies hanging off Fatfield Bridge. The main achievement, I think that for for 2018 - we had 12,557 knitted poppies hanging off the bridge on streamers - which people thought were fantastic [Thats one for each man in the DLI killed]. They were created - we had ‘knitting in public days’ and when it rained we had ‘knitting in the pub day’ which was even better. All of these things, all of these links, are available through our website.

TT: And how did the local community respond to these initiatives?

PW: Well, we like to think very positively. Certainly through the website we get lots of contacts. Just last week, I got a photograph of Robert Pestell’s five children. I haven't got a photograph of Robert yet and the relations are searching for a photograph of Robert for whom there was a benefit at Washington Cinema. I think in 1919 the five children were being looked after by the community, if you like. And I think that sense of ‘community’ has gone on. They get a very big turn out at Washington Village War Memorial. When we started doing little ceremonies at Fatfield War Memorial 10 years ago. Jimmy from the club would turn up open his car bonnet, put his cassette player on and play the Last Post. This year, we had about 500 people there. So that's been very gratifying. None of this could have been done without the stories that people tell us and the artefacts that this show us. I mentioned Edith Loos Drummond - they still have the bullet that was taken out or Richard Drummond's head in a box in the house. We've named a street on a new housing estate after William Forster who was who lived in one of the houses in that area.

Peter Hart, bless his cotton socks, comes up to talk to Durham Western Front Association every November. And the Peter Hart talks to the community, he will sometimes stay over for us to do a talk, and we get 70 people at the club talk listening to Peter talk about the First World War, in what I think the word is, in his ‘inimitable style’ that he has.

We get great support from the local council, who restored one of the memorials where a Celtic Cross on the top of the had blown off in a storm and they paid for that. So we think that the community has been very supportive in terms of accepting the information, reading the information, liking the information and chipping in with their own stories - because these fellas were everybody's grandad.

TT: And finally Peter where can people learn more?

PW: Right, a website run by Lancastrianne is wwmp.weebly.com i.e The Washington War Memorials Project and they'll find a contact for me and for the group of people that we work together with doing the research. So it's all there on the website.

TT: Peter. Thank you very much for your time.

PW: You're very welcome.

TT: You have been listening to the 'Mentioned in Dispatches' podcast from The Western Front association with me, Tom Thorpe. Thank you to all my guests for appearing on this addition. The theme music for this podcast was George Butterworth’s ‘The Banks of Green Willow’. It was performed by the BBC National Orchestra of Wales, conducted by Chris Gussman and produced by Biz Records. This recording is part of a collection of orchestral works by Butterworth performed by the BBC National Orchestra of Wales and supported by The Western Front Association. This is available from all good record shops under the record code BIS2195. Until next time.

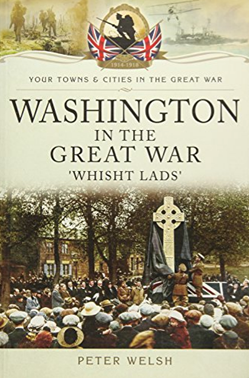

Washington in the Great War by Peter Welsh is available in paperback and for Kindle.