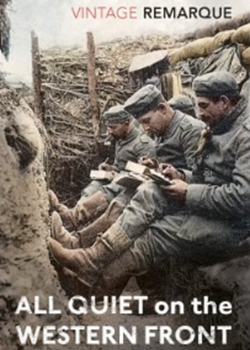

All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque

- Home

- World War I Book Reviews

- All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque

'This book is to be neither an accusation nor a confession, and least of all an adventure, for death is not an adventure to those who stand face to face with it. It will try simply to tell of a generation of men who, even though they may have escaped shells, were destroyed by the war.'

This is the epigraph of Erich Maria Remarque’s anti-war novel, All Quiet on the Western Front.

Released in 1929 and based upon his own experience as an infantry soldier, Remarque’s account of the First World War supplied a brand-new perspective of the soldier’s experience. While war literature had previously been dominated by generals with a tendency to romanticise warfare, each scene of All Quiet on the Western Front is informed by the horror and brutality of trench warfare.

The novel takes the form of a first-person narrative, that of Paul Baumer. He is a 19-year-old German infantry soldier serving on the Western front, whose initial reflections on joining the armed forces denote excitement for a grand adventure alongside his friends. As the narrative progresses, Paul’s psyche progresses in line with developments in the war. The historical realities at work illuminate how many fresh-faced soldiers did not realise how they came to be the ones on the front line, having had no real life experience – or tactical training - between school and battle.

These psychological struggles are mirrored in the technological advancements of warfare first displayed in this war, with Paul referencing ‘new planes’ and ‘new guns’. As his friends perish one by one, he no longer stops to mourn as he realises that emotional disconnection is the only way to survive the overload of chaos. One of the most pressing questions throughout the narrative is who will inherit Kemmerich’s boots, first mentioned at the start of the novel. Each character who inherits the boots dies, almost reflecting the cheapness of human life in war; on the front line, good quality footwear is more valuable than a human being.

The visual imagery portrayed throughout the narrative is imaginative rather than literarily charged, enabling the reader to grasp the truly graphic sights soldiers were exposed to in the First World War. Paul talks of ‘men living with their skulls blown open’ and soldiers running ‘with their two feet cut off’ as ‘they stagger on their splintered stumps into the next shell-hole’. This intricate detail is not used to shock, but to demonstrate how these images became seared into the brains of the young men depicted in the narrative. No longer able to communicate with their family, friends and even themselves, the youthful infantrymen of the First World War became the lost generation.

The suggestion of universal humanity in the blurring of enemy lines is perhaps the greatest anti-war message communicated to date. Upon its release, this humanity within the narrative tapped into the sorrow felt around the globe. If you have not read this already – you should. It is one of the most profound novels of its generation, condemned by the Nazis and an historical document of both the changing nature of warfare and modernity.

Review by Chloe Egan, Liverpool Tour Guide, Western Front Association member