In Haig’s Shadow: The Letters of Major– General Hugo De Pree and Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig (editor) Gary Sheffield

- Home

- World War I Book Reviews

- In Haig’s Shadow: The Letters of Major– General Hugo De Pree and Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig (editor) Gary Sheffield

Greenhill Books

£19.99, 217 pages, including 2 appendices

ISBN 9781784383534

Some might think that there is little left to say about Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig. Lionised by his brothers–in–arms in the 1920s, Haig’s reputation was systematically demolished in the 1930s to the point where, for many, he came to represent something of a pantomime villain. More recently a more measured assessment has prevailed in academic circles and after the passage of a century Haig’s reputation has been partially rehabilitated.

The editor of this collection of letters Professor Gary Sheffield did, of course, play a key role in propagating a more sympathetic view of the Field Marshal in his book ‘The Chief: Douglas Haig and the British Army’ which ranks alongside other studies from the likes of John Terraine, John Bourne and Brian Bond.

This collection of letters and documents surfaced as a result of Professor Sheffield being introduced to Janet, Lady Gover, Douglas Haig’s great–niece. A brief foray into Lady Grover’s papers opened up the opportunity to meet other family members and before long it was evident that there was enough material for a book – effectively a fulsome addendum to ‘The Chief’.

Hugo De Pree was Douglas Haig’s nephew and a distinguished soldier in his own right. This book contains correspondence between these two men, plus letters and writings from other family members and a number of prominent individuals. For those readers that are interested in Haig as a private person (rather than as a military leader) his letters to Hugo and, in particular, to his favourite niece Ruth De Pree, reveal a man who enjoyed the simple pleasures in life and who occasionally found the mantle of military leadership a difficult one to carry.

Aside from the insights into Haig’s character the material relating to Hugo De Pree’s war service carries much which is of interest.

Sadly, the correspondence covering the first two years of the war are lost but there is plenty of quality in what remains. De Pree was very influential in the planning for the Battle of Cambrai and an insightful summary which he wrote afterwards is included. In August of the following year, as commander of 189 Brigade, 63rd Royal Navy Division, De Pree courted controversy by refusing an order to attack and was subsequently sacked. He was later exonerated and the papers relating to this episode makes compulsive reading.

For me, the most interesting section of the book is the material relating to the writing and publication of Haig’s official biography. As one of her late husband’s three executors, Lady Haig was anxious to ensure that Haig’s legacy was properly articulated. As is evidenced in the correspondence as the process unfolded, Lady Haig’s behaviour became more and more unpredictable. A number of preferred authors declined the opportunity, partly as the result of Dorothy’s antipathy. Duff Cooper was famously appointed but after twelve months or so Lady Haig decided to write her own biography (published in 1936 as ‘The Man I Knew’).

There was a legal tussle over access to the Field Marshal’s diaries and a series of acrimonious exchanges involving, amongst others, Brigadier General Sir James Edmonds, the official Great War historian. The question of ‘who owns history?’ is writ large in these exchanges.

Other sections of the book cover the death of Hugo De Pree’s son (named Bourlon after Cambrai) in a Prisoner of War camp in 1942 and Ruth De Pree’s affectionate memoir of Douglas Haig.

My interest in this latest volume of letters was piqued at a recent Malvern Festival of Military History. It was evident during his presentation at the festival that Professor Sheffield was surprised to have come across such an extensive collection of primary documents so late in the day. He reflected that the inclusion of this material in the earlier biography would have brought more ‘light and shade’ to the work but went on to say that the extent and quality of the collection definitely justified the publication of a stand–alone book – a view that this reviewer would endorse.

Whether this latest collection of letters and documents represents the final word on Haig’s life and service it is impossible to say but it does allow the reader to see beyond the stiff upper lip and moustache which characterises public perception of a man who many would argue was responsible for winning the First World War.

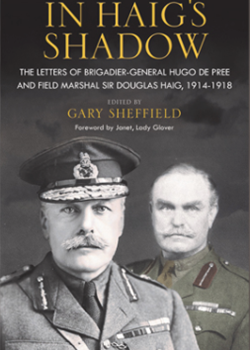

My only grumble – and it’s a small one – is that there are no photographs of the people featured in the book. Aside from this very minor point, ‘In Haig’s Shadow’ is an informative and entertaining book to read. Furthermore the excellent notes made by the editor provide valuable context throughout and, notwithstanding the variety of topics covered, the narrative flows freely and logically.

Recommended.

Review by Phil Culme