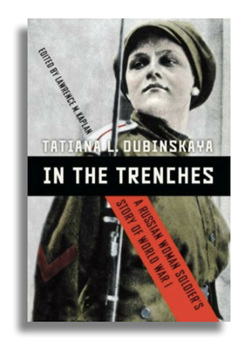

In the Trenches: A Russian Woman Soldier’s Story of World War 1 by Tatiana Dubinskaya

- Home

- World War I Book Reviews

- In the Trenches: A Russian Woman Soldier’s Story of World War 1 by Tatiana Dubinskaya

£20.00, Potomac Books: University of Nebraska Press,

192pp, pb, maps, notes, index,

Introduction by Lawrence M Kaplan.

ISBN 9781640121966

In the Trenches is an odd, unstructured and episodic book, but an undoubtedly powerful one. Although presented as fiction, the story clearly reflects Dubinskaya’s own experiences, which have been merged by the editor with parts of her autobiography Machine Gunner (1963), which gave more emphasis to revolutionary talk among the troops.

The heroine, Zina, runs away from school and her comfortable middle–class home at the age of fifteen to join the army, and serves in the trenches on the Galician front between 1916–1917. At first, she pretends to be a boy but is soon recognised to be female. Briefly imprisoned and awaiting recall to her family, she escapes, returns to her platoon, is accepted and looked on almost as a mascot.

Being literate (a rarity in the ranks of the Russian Army) she becomes the letter writer for her platoon, is promoted to cavalry scout and takes an Austrian soldier prisoner for which she wins a medal. Surprisingly, she only recounts one episode of near rape by an officer who is driven off by a comrade. The only other woman soldier she meets (although there were many others) clearly works as a prostitute for her company.

The author shows the Russian Army to have developed little from the time of the Crimean War. The casual brutality of the officers is shocking, floggings are frequent. Officers are often drunk, and the colonel is addicted to iodine. So harsh are conditions that even the cockroaches move onto a stove for warmth, and a sentry she is sent to relieve is found frozen to death at his post. As for the action, attacks are sporadic and inconclusive, described in an almost impressionistic way.

There are tender moments – a description of a soldier staying all day with his dying horse, and an episode after a battle where Zina watches a soldier carefully binding up a wounded pigeon’s wing. Zina’s comrades differ in their political feelings, some agitate for revolution, others believe in the status quo – despite its hardship and inherent cruelty. One old peasant is flogged to death for giving his landlord poor honey, a soldier weeps to hear his family’s only cow has been requisitioned by the state, bringing ruin upon them.

Medical services are primitive, medicines scarce, hygiene non–existent. The fast–moving frontiers of the war dictate the creation of temporary improvised operating theatres. Amputated limbs are thrown out and fought over by dogs. As conditions worsen, starving soldiers cut chunks of flesh off a live pig.

Any comparisons with All Quiet on the Western Front do not bear examination. That classic story has a structure and its characters are well defined. Here the style and conversations are often stilted, characters are one–dimensional, questions often answered with non–sequiturs – ‘Why aren’t you occupied’? an officer asks Zina, ‘It’s not nice to fight’, comes the reply.

However, despite its strangeness, this story deserves its place in First World War history. Post–war, Dubinskaya married four times, became a journalist and writer, and a communist informer. Of her wartime experiences she said, ‘I saw a lot of misfortune and very little happiness’. One can believe it.

Reviewed by Elizabeth Balmer

[This review first appeared in the January 2021 edition (no.121) of the journal of The Western Front Association Stand To! Members receive each of our journal Stand To! and member magazine Bulletin three times a year. Digital Members received this electronically. All issues are available to members via their digital login.]