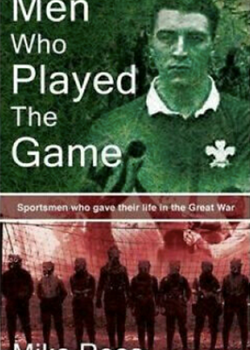

Men who Played the Game – Sportsmen who Gave their Life in the Great War by Mike Reese

- Home

- World War I Book Reviews

- Men who Played the Game – Sportsmen who Gave their Life in the Great War by Mike Reese

Seren Books, £17.99

268pp, 18 ills.

ISBN: 978–178–172–286–2

[This review first appeared in Stand To! 109 June 2017 (Special Edition)]

From Edward Poulton’s 1919 tear–stained hagiography of his beloved son, the England pre–war Rugby Union captain Ronald Poulton Palmer, books about sport and the men who ‘played the game’ before going to war have always been of interest.

In more recent years there have been several excellent books published covering aspects of sport and sportsmen in the Great War. Andrew Riddoch and John Kemp tackled football in When the Whistle Blows, Stephen Cooper used Rosslyn Park as a case study for Rugby Union in The Final Whistle and individual biographies include Phil Vasili’s detailed study of Walter Tull. Mike Rees has taken on the ambitious task of looking at sport in general rather than focusing on one institution, sport or individual in his book Men Who Played the Game.

This is quite an undertaking. Rees rightly points out that by 1918 a ‘sizeable minority’ of the era’s top sportsmen had fought in the Great War with many of them losing their lives and there are hundreds of stories from which to choose. Clive Harris and Julian Whippy’s excellent The Greater Game – frequently referenced by Rees – took a similarly broad approach in terms of the sports covered, but they at least narrowed the focus on a handful of individuals.

Some of the men featured already have entire books written about them, men such as the aforementioned Ronald Poulton Palmer and cricketers Percy Jeeves and Colin Blythe. Others too really deserve biographies of their own. And the breadth of what Rees is attempting to achieve can be the book’s downfall. Characters drift in and out of the narrative like rolling–substitutes in a game of five–a–side football and the reader is left wanting to learn more about personalities as colourful as Sandy Turnbull, Tony Wilding and David Bedell– Sivright.

However laudable it is to try to cover so many stories and thus commemorate so many men, this, at times, comes at the expense of accuracy. Here Edgar Mobbs is playing for Toulouse rather than against them as he did; Frederick Kelly is hit and wounded by a shell fragment when his diary clearly records a stray bullet to the foot: and most jarringly of all Northampton RFC’s home ground is ‘Franklyn Gardens’. While this may seem pedantic such basic factual errors undermine one’s confidence in the text as a whole.

At other times instead of providing the reader with new insights based on fresh research, some of the same old myths are regurgitated. As many have before him, Rees has Mobbs addressing a rugby crowd in September 1914, at a time when all matches had already been scratched. And poor Blair Swannell (admittedly a favourite of mine) once again has his character assassinated well over a century later by the poisonous pen of Australian rugby contemporary Herbert Moran, a man with whom he doubtless shared a grudge but whose brief yet vituperative paragraphs on Swannell are far too often trotted out and treated as gospel. This is unfortunate as there was so much more written about this intriguing and endlessly fascinating character.

The strength of the book undoubtedly lies in the early chapters which place sport, society and war in context. Rees writes with clarity and pace and is never dull. The sheer scale of the undertaking means that this book will suit the general reader looking for a snapshot of these sporting stars and of the battles in which they fought. But for those unsatisfied and wanting to know more there are, thankfully, books which go into the lives of these remarkable men in much greater depth.

Review by Graham McKechnie