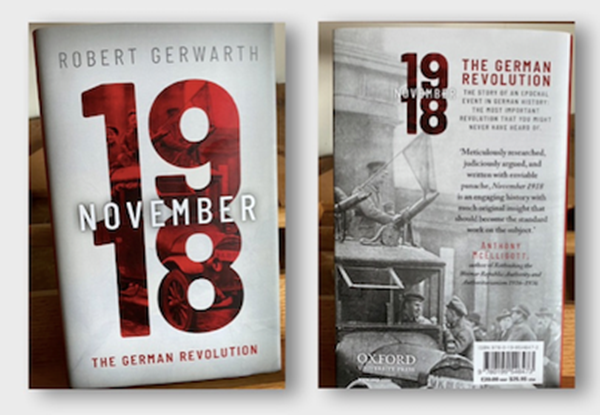

November 1918: The German Revolution by Robert Gerwarth

- Home

- World War I Book Reviews

- November 1918: The German Revolution by Robert Gerwarth

£20.00, 368pp, maps and black and white illustrations.

ISBN 978019954647 3.

What a delight – a serious, deeply researched and academic work by a perceptive author with a fascinating ‘story’ line supported by a huge bibliography and extensive notes and references.

Robert Gerwarth studied history in Berlin and Oxford.

He is both an established author and Professor of History at University College, Dublin.

Oxford University Press, to whom I raise my hat, has published the book at the highly attractive, accessible, unacademic recommended retail price of £20.00 (Search around - a new copy can be found for under £15). As I have noted in previous editions of Stand To! academic books – some failing to deserve such acclaim – have long been foolishly and discouragingly over–priced. Perhaps, at long last, academic publishers are beginning to realise that over pricing destroys purchasing incentive.

As the author notes, ‘November 1918 has a special resonance and place in German history’. His great skill is explaining this resonance and the complex consequences of losing a war, the Kaiser, major food shortages, a hostile and threatening military and left– and right–wing political opinions at home. To this must be added geopolitical influences and consequences for Germany after the armistice. Even in the spring of 1918 the leaders of the German Army believed they could win the war – even if many in the ranks and at home demurred. From a modern viewpoint, whilst Wilson’s 14 points certainly influenced Germany’s late acceptance of the Armistice, at Versailles, Germany – its soldiers, politicians and the public – judged the reparations dictated as crippling, unfair and harsh.

Regardless, they were less so than the terms Germany had imposed on France after the Franco Prussian War or on Russia by the Treaty of Brest–Litovsk. Gerwarth convincingly reveals the length and breadth of Germany’s military defeat and the toxic political imbalance it created – including naval mutiny and the Kaiser’s decision to cut and run from his nation and responsibilities. German morale, military and civilian, had reached an all–time low in the period leading to the Armistice.

Both political belief and national confidence were lost. To these the author adds the problems of Germany’s post–war political imbalance and the costs of war – to the military, the population, agriculture, industry and finance. In offering what is a confident and positive overview of post–war German governments, which are frequently regarded as ‘failed’ and the triggers for Nazism, his introduction offers a cogent, ‘… alternative interpretation of the Revolution’.

Rather than accept that the Weimar Government was a failure he evidences its many achievements in a time of political and moral complexity and instability. His analysis offers both an impressive overview of post–war Germany and a firm corrective to the negative and hostile views which condemn Germany’s complex post–war politics simply as an inevitable journey towards Nazism. As such, and because of the book’s quality of research and skilled authorship, this is a book which deserves high recommendation.

Review by David J Filsell