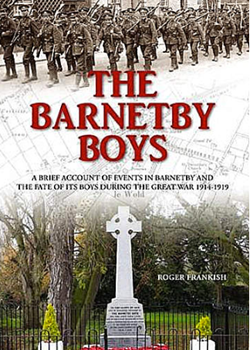

The Barnetby Boys by Roger Frankish - A north Lincolnshire town at war

- Home

- World War I Book Reviews

- The Barnetby Boys by Roger Frankish - A north Lincolnshire town at war

Reveille Press (18 Nov. 2014)

322 pages

‘The Barnetby Boys', though non-fiction, you are soon immersed in the drama of a world as rich as the BBC’s Radio First World War drama series ‘Homeland’.

Think, if you will of the ‘Archers’ set a hundred years ago, broadly the generation of 1900 to 1925, though instead of farming, Barnetby was a hub of employment on the railways and here the heartfelt dramas, the births, marriages and many deaths happened. You soon feel part of the lives of many families, Great Central Railway Barnetby branch Loco.Depot, numerous societies, and Church. It’s as if you witness events as they unfold through the eyes of a well-informed and educated local vicar, reflecting some decades after with the benefit of hindsight. This is someone who knew many of the people through christenings, marriages and services of commemoration and while we know this research is coming from census returns, soldier archives, and archived newspapers we nonetheless feel that the information is revealed and stories told. The nature and focus of fund raising activities and tell their stories such as Miss Ffrench here, nd the children of Barnetby raise money or collect eggs, first for the Belgian Refugees and then for ‘our boys on the front’ and finally of course to erect a memorial to those who died.

Begun as so many projects like this do as a record that would honour of those who served, and those who served and died who appear on the Barnetby Roll of Honour, ‘The Barnety Boy’ pulls together every possible record and source.

'The Barnetby Boys' has the detail of a Pre-Raphaelite Painting.

A man marries you know his family, his schooling, and work. You know his bride and what she wore and who was at the wedding. You may know that she has been involved in some of the village fundraising. He goes to war. She may attend other village events then become a nurse and head to France herself. And then of course we join the men on the Front, in the trenches, going over. We see them in the trenches writing home, but we also see the hawk’s view of the battlefield as particular events, involving a tight body of men, unfold. Some die, many are wounded, some go missing, some become prisoners and all fold, 4/5 return. There are 174 men listed on the Roll of Honour; each, or almost everyone, is treated like a close relative remembered. 34 were killed.

As with so many projects like this that are a ‘labour of love', there is a personal context as the author's young father served and survived, the author living in the family home until he was himself a young man and now living a few houses down the street a hundred yards away. Authors do this from compulsion, with a sense of duty and in respect. And in remembering these men they anchor the present to the past through the memorials in our towns, churches, in our post offices and railway stations. We visit their graves too, or where there is no grave, where their names appear on memorials in Belgium and France. And remarkably, and somewhat humbly, the spot where a man was killed and buried in the field is marked in a photograph and on a map. For those who feel compelled to follow in the footsteps of the men who served, here one can follow some all the way to their final step or stumble.

The many stories and angles are told in 'The Barnetby Boys' in an approximate chronology from 1914, sometimes looping away to complete one story before returning.

At the outbreaks of war in 1914 the 1st Lincolnshires are brought up to strength, departed from Portsmouth and went to Mons on the 19 August 1914. Meanwhile, the 2nd Lincolnshires are duly brought back from a sojourn in Bermuda via Nova Scotia, and they too are ready for action by November 1914. There are also two territorial battalions who were on annual training at Bridlington in August 1914. They too are duly rallied and on 15 September 1914 called up to volunteer. For a moment, like turning the pages of a diary, we skip through dates until we pause too for our introduction to what is a primary thread; the 10th Lincoln’s or ‘Grimsby Chums.’ We learn how they are recruited on a wave of local fervour, as occurs across Britain. And once raised the ‘chums’ are trained from 4 December 1914 to 15 June 1915.

The detail makes ‘The Barnetby Boys’ as much a reference as a collection of stories.

We understand the author’s attachment to this subject when he shares his father’s photographs, biography and service history. We also follow staff changes on the railway, water shortages for the steam locomotives, and the intriguing insight into correspondence with a relative in the US, then raising funds for the Belgian Relief Fund.

Quite soon we understand the drive, purpose and value of a book such as ‘The Barnetby Boys’ when we learn that Campbell Caward was killed in action on 13 October 1914 and John Marsh on 14 October 1914. Here is a considered, even compelling act of remembrance as each name on the Barnetby Roll of Honour is remembered. You are left feeling that you could know little more about these men if you spoke personally to their teacher, sister, friends or employee. In a sad way it sets the events on the Western Front, where all the Barnetby Boys serve in a broader historical and geographic context: while they were at war, the rest of the world were busy too.

The Battle of Coronel is explained in a succinct essay as it is here that on 1 November 1914 Able Seaman Herbert Ball was lost on the HMS Good Hope. And as we contemplate the horror of drowning in the South Atlantic back home there is marriage, a children’s service for the Belgian Relief Fund and an evening listening to gramophone records, also to raise funds for the Belgian Relief Fund at the Women’s adults school.

Apologetically, the author complements his essay on the Battle of Coronel with the Battle of the Falklands - even though there were no ‘Barnetby Boys’ loses here you feel glad for this interjection as it suits the tone of the book. This is a collection of carefully researched insights that is offered to readers three or even four generations down the line. ‘The Barnetby Boys’ is a history, a series of biographies, and a social history. On the one hand, it holds a magnifying glass over this part of North Lincolnshire, while at the same time looking far beyond to report and share the adventures and misadventures of those who left to serve for ‘King and Country.'

I like learning that Miss D Partridge won the Ladies’ Egg and Spoon race in June 1915 and that notably on 23 August the first female railways porter reported for work at the Great Central Railway. It is a detail that makes the story familiar while hinting at the cracks in the fabric of society as it would change and continue to do so fundamentally for the next 100 years.

‘The Barnetby Boys’ is not a Division History, yet there is an element of this style as we find our Barnetby Boys and learn their fate.

In a historiography full of the stories of those who died, ‘The Barnetby Boys’ gives a far more balanced impression as we here too of those who were wounded, and, of course, those who came back which modern readers are often surprised to learn, was the majority. While shocking to know that 1/5th did not return and quickly appreciating what impact this would have on a close-knit community, 4/5ths did return.

The Battle of Loos is reported in truncated form, as the Lincolnshire men only took part from 25 September to 8 October. It's as if our perspective is limited to the letters they may have written home - a partial rather than a complete view. Some died, many were wounded, while others were taken prisoner. The news filtered back in dribs and drabs, sometimes it was inaccurate: a man reported killed when he had been captured for example. A soldier reported ‘missing’ leaving family and friends in dreadful suspense for many months.

It isn’t hard to imagine how awful these times must have been for the likes of Mr & Mrs. Worrall who had three sons serving on the front: Jim was captured at Loos while Joe and Arthur were injured. Not for them the awful experience of the Halls who received the news of the death of their son L/Sgt T Hall on 10 December 1915 and then a package containing nothing more than his cap badge and a few photographs. And how would the family of Cpl J W Lobley feel in early January 1937 after a body was found identified as Lobley by the service no. 1560 on his boot.

At times, it is as if Roger Frankish is standing on a plinth himself in Barnetby. He shines a light on all that could be relevant to the village, from the men and their memorials, to ‘divisional history’ like accounts of the key Lincoln regiments. At the same time he keeps a keen eye is forever on the local newspapers for the actions and events in halls and places of work: fundraising for ‘our soldiers on the front’, replacing fundraising for the Belgian Relief Fund. Men on leave make the news as much as men killed, a death on the front is contrasted with a local story of a 15-year-old girl who chokes when a gooseberry gets stuck in her throat. By the end of November Ms. Ffrench, who has cropped up in various volunteer fundraising activities, has gone to Lady Sheffield’s hospital as a nurse.

If the action on the Western Front is the main dish, then the weddings and the detail is the desert.

While we at one stage we read about the detail of an action, the next we are joining the wedding of Miss Kate Rowe and Cadet C Bradley, which includes such fine details as ‘the school staff had presented her with a combined cream and sugar container and a silver holder.’ I could imagine attending a presentation on Barnetby in the Great War and a story starting with, on the one hand, being shown a boot, and the other a sugar container. These personal items create an extraordinary empathy for the participants. A man identified by his boot long after the war, a wedding gift a reminder of the marriage during the war years to a man who never returned. Too often we experience the Great War only as a period of death, yet quite clearly life went on.

Imagine a very well informed guide on a tour bus through history.

As we are driven from west to east, on his right, we have in the North Barnetby, North Lincolnshire, and Britain while on our speakers left, to the south, we have the English Channel, France, and Flanders. Somehow, his unenviable task is to keep our interest as the chronology of time tells us what was taking place on the home front, with working men and fund raising women; while to the south the soldiers of Barnetby, mostly aggregated into the 'Grimsby Chums' fight on the Western Front. Somehow, our guide, the author Roger Frankish, must hold our interest while mixing what to some would be incompatible ingredients. It makes for an eclectic read, but one that Roger Frankish pulls off. You appreciate what he has pulled together and the value of 'The Barnetby Boys' both for its narrative and the curation of a multitude of minor and massive events, from the minuscule of a wedding gift to the scale of a divisional attack on the Western front.

Readers may not be used to rocking without warning between events on the front with those at home. For example, in the same breath, we learn that Thomas Bramley was killed in action 17 April 1918 during the fighting of the 34th Division while on 23 April 1918 of Miss Jane Hayward got married. She ‘looked charming in a gown of navy blue taffeta trimmed with a gold hat of white satin with blue chiffon, carrying a sheaf of lilies and wearing a gold brooch’.

‘The Barnetby Boys’ is a tour de force of individual research: no man is forgotten.

Take for example Pte. W.S. Witty, who in forensic detail we read that he died and where he is now buried. Or where Pte George Nicholls was buried within 10 square yards. By the end of 1918, men are returning from prisoner of war camps, men like Pte W. Pretty and Pte J. Worral, who had been away for three years and three months.

The Great War washed close, then over Barnetby and much of the world, then receded. By 29 January 1919 the community is thinking of erecting a memorial. While with men returning there are still please for information on those still missing and unaccounted for.

There’s more news of the Ffrench family with news on 23 August 1919 that on 16 August 1919, age 19, Ernest Ffrench had been killed in action in the 3rd Afghan War. We too easily forget that despite the Armistice of 11 November 1918 other battles were still being fought, for Russia between the Bolsheviks and the White Army, in Afghanistan, and later between the fledgling Polish nation and Russia.

There were Peace Celebrations on Saturday 19 July 1919. This included a Sports Day. The author carefully lists all the prizes, which includes wonders such as the ‘women’s thread-needle race’ and a ‘slow bicycle race’. By November 1919, fund raising for and decisions over the war memorial are a matter of concern.

In 1920, the widow of Pte Charles Braithwaite remarried.

In December, work began on erecting the memorial while come the 19th further funds are being raised to add names.

It is fitting for what at times is a quixotic history, social and community account of the war.

It is intriguing because I’m not aware of any other author doing it, to get a sense of how the First World War has shivered out of people’s daily lives. A line such as ‘there was no World War One news ’til Sept 1922’ suggests that people are already moving on - though of course, they had no inkling at all that the Great War could be or would the first of two world wars.

Then in 1924 the reporting and the book jolts to a halt like a redundant train coming into a siding. At this point, a conclusion, drawing in the many threads would round it off. It is perhaps several books, and several leaflets all threaded together to form one entity. It does something extraordinary by reaching back and forth between the home front and the Western front, and also by reaching back to the occasion when so many of the men who served or served and died were born.

Appendix 3 gives us comprehensive biography and service history of Lord Worsley, who died 19 October 1914.

The roll of honour on which the entire book is based is on page 302. The Barnetby Boys is more than a companion guide to this; it is itself a memorial and a commemorative act that gives these men their lives back. Through ‘The Barnetby Boys', we come to know them and the community they left behind.

Copies can be bought from the author and Amazon.

Review by Jonathan Vernon