The British West Indies Regiment: Race and Colour on the Western Front by Dominiek Dendonvan

- Home

- World War I Book Reviews

- The British West Indies Regiment: Race and Colour on the Western Front by Dominiek Dendonvan

The British West Indies Regiment: Race and Colour on the Western Front is a compelling and meticulously researched examination of the experiences of Black Caribbean soldiers who volunteered to serve in the British Army during the First World War. Dendonvan's meticulous research instils confidence in the book's accuracy and reliability. He sets the West Indies in context, looks at the formation and training of the men for front-line combat in England, and then covers the deployment of the British West Indies Regiment to the Western Front not as infantry but as labourers and stevedores.

Dendovan points out that ‘representatives from Caribbean countries and territories are generally absent from First World War commemorative events’. DD KL 98 Efforts should be made to rectify this, not least commemorating the service of men in the BWIR during Black History Month each year.

Dendovan explores the complex interplay of race and colonial dynamics, highlighting how black men from the West Indies faced not only the horrors of war but also systemic racial discrimination and prejudice. Their unique challenges, such as being relegated to non-combat roles despite their willingness to fight, underscore the need for their service to be acknowledged and commemorated.

Dendonvan's narrative is engaging and informative, drawing on various primary sources.

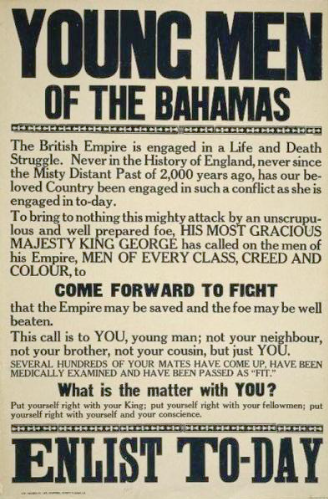

When war broke out in 1914, the British island colonies in the West Indies (Jamaica, Barbados, Bermuda, the Bahamas, Trinidad & Tobago, Windward Islands, and Leeward Islands) quickly pledged their support to King George and the British Empire. Men from the West Indies volunteered to fight, and the various islands pledged money and materials to the cause.

Above: Recruitment poster from the Bahamas calling upon men to fight so that 'the Empire might be saved'. Courtesy Library of Congress.

Caught up in the moment, seeing recruitment posters, reading press reports, and attending rallies, thousands of West Indian men enlisted. They wanted to prove their worth and express their pride as British subjects.

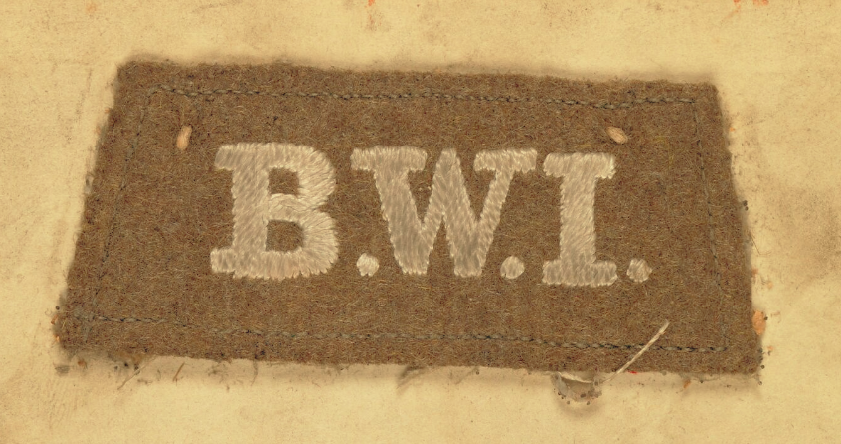

The British West Indies Regiment was formed on November 5, 1915. It ultimately consisted of 11 battalions, with a total of 15,600 men.

‘The West Indians genuinely felt British; they identified with Britain and its Empire. English was mostly their mother tongue, and British was their culture and education’, writes Dendovan. The West Indian press widely reported in favourable terms the arrival on the Western Front of tirailleurs senegalais, tirailleurs algeriens and Indian troops. Such news coverage convinced volunteers that they would serve in the British Army as soldiers.

There was a belief that through showing loyalty unto death, they would be rewarded after the war, something often quoted by Marcus Garvey. In his telegram to the Colonial Office on 16 September 1914 on behalf of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) to express support and loyalty ‘mindful of the great protecting and civilising influence of the English nation and people … and their justice to all men, and especially to their Negro subjects’.

(Garvey) hoped that fighting on the battlefield would bring equality and political power. Garvey was yet to become the influential figure he would become, but many others, including well-read local newspapers, shared his sentiment.

On 19 June 1915, the Federalist Grenada People praised Barbados for sending a contingent to the front so ‘she may take rank with Canada, and Australia, South Africa, and Newfoundland (dominions with home rule).

Above: Recruiting and Training in the West Indies: Trinidad: A recruiting meeting held at Port of Spain, Trinidad, 1916. Image: IWM (Q 52436)

Detail from the recruiting meeting held in Trinidad

The men were volunteers; there was never any conscription. They thought they were signing up alongside fellow countrymen across the British Empire to ‘do their bit’ as soldiers fighting Germany and the Kaiser, the apotheosis of democracy.

Caribbean men believed they could prove their worth. They wanted to prove their courage as fighting men. They had a sense of duty and a desire to belong to the King’s Empire and to defend the Mother Country. Though resulting from centuries of slavery and emancipation, the African diaspora in the West Indies was British by education, religion, and culture. There were financial incentives to join up (the pay was better for labourers), and the Church got behind in recruitment. Barbados, remember, was known as ‘Little England’.

According to Dendovan, many recruits were ‘educated people who read newspapers, wrote home, reflected on their situation, debated, and were ready to take action when unjustly treated.

On 9th November 1915, the first ship of recruits for the British Army set sail from Jamaica; it was hailed as Jamaica’s ‘arrival on the world stage’.

The analysis of the soldiers' training in England and service on the Western Front is particularly poignant, showcasing their remarkable resilience in the face of adversity.

Based in the extensive Seaford Camp, Sussex, for training, in October 1915, there was a public protest by the soldiers as they had not been paid. An ex-policeman led the protest from the British Guiana, Henry Somerset. ‘No Money, no work’ chalked on the walls. Forty men were involved. Their uniforms were confiscated, and they were repatriated. That was the end of their war.

The siting of the Seaford Camp exposed it to the total onslaught of southwesterly gales blowing up the English Channel. Over its first winter of operation, 1914/1915, many men were billeted in Eastbourne. A year later, the men of the BWIR faced the same brutal weather. The West Indian Contingent Committee was set up at the end of 1915, and warm clothing, socks, underwear and gloves were provided; the men were not billeted in the local community. From 20 October 1915 to 30 January 1916, 19 West Indians succumbed to illness.

Black Doctors could be given the rank of Captain; otherwise, black soldiers of the BWIR were never given a commission. There was an instant when an officer ordered the men of BWIR to another camp. The doctor considered this unhealthy, and after many arguments with the British Officer, they were not moved.

Dendonvan doesn’t shy away from the harsh realities these men endured, including the inequities in treatment compared to their white counterparts and the racial tensions that persisted even after their service.

Though trained to fight and bear arms, once in France, their transport stopped short of the front line, and they were put to work as labourers and stevedores, loading and unloading trains and wagons, digging trenches and roads, and building artillery emplacements.

The exclusion from combat was considered a racial slur and deeply resented. (DD KL 643)

In some areas, when coloured troops were banned from visiting cafes and YMCA huts, their senior officers lobbied on their behalf that although they were carrying out labouring duties, arguing that they had been trained as soldiers and bore arms and should have soldierly privileges afforded to them. (Horner A E Op Cit., P.3,7,32,39-40, 49) The men of the BWIR were considered to be ‘a better-educated kind of black man compared to those from Africa’. They were only permitted to visit cafes where no women were employed. (KL 899)

Eight men of the BWIR received the death sentence: Four were commuted to penalties of five to 20 years of penal servitude (one for sleeping at his post, two for striking an officer, and one for mutiny). The remaining four were executed; two had been condemned for murder, a third for repeatedly striking an officer and the 4th for desertion.

Through their individual war experiences, many West Indians were changed, and many became activists. The communities the men returned to often expected veterans to become leaders, and many did. In Grenada, Dendovan points out that when the governor appointed 18 new Justices of the Peace in July, 8 were officers and non-commissioned officers who had served overseas.

One of the book's strengths is that it sets the BWIR's experiences in the context of colonialism in post-war Caribbean society. Dendovan shows how the Great War experience of black soldiers serving in the BWIR galvanised and politicised many of them to seek independence from colonial rule after the war. He explores the long-term impacts of the war on these soldiers and their communities, providing an understanding of how their service influenced movements for equality and Independence in the Caribbean. Several veterans emigrated to the US and became involved in Black Activism there.

Men from the BWIR won military honours, including five Distinguished Service Orders and nine Military Crosses … in all, 166 were decorated.

Many books referenced by Dendovan are reviewed elsewhere on the WFA website in the context of the African-American experience in the American Expeditionary Force.

In December 1918, around 8,000 soldiers of the BWIR stationed in Taranto, Italy, had been waiting for several months to be demobilised and given a passage home. The last straw was when they were ordered to clean the latrines used by Italian soldiers.

On 29 April 1919, awaiting demobilisation, fighting broke out between soldiers of the American Expeditionary Force (white) and men of the BWIR (black) in Winchester.

19 July 1919, no troops from the West Indies took part in the Victory Parade in London

The war ’swept away the aura of the superiority of Europe’s civilisation and the idea of white supremacy’.

Overall, "The British West Indies Regiment: Race and Colour on the Western Front" significantly contributes to military history and postcolonial studies. It offers a powerful tribute to the often-overlooked Caribbean soldiers of WWI and is essential reading for anyone interested in the intersections of race, colonialism, and military history. Its significant contribution to postcolonial studies will stimulate intellectual engagement and further research in this field.

References

Dendovan, D. (2019): ‘The British West Indies Regiment: Race and Colour on the Western Front’

Further Reading

Dendovan, D (2021) ‘Mentioned in Dispatches’ Podcast > https://bit.ly/4eWCYoz

Jamaican Volunteers in the First World War > https://bit.ly/3W4PFGQ

BWIR by the IWM > https://bit.ly/IWMBWIRWW1

Black British Veterans of WWI tell their story > https://bit.ly/3xPreDp

How the West Indies helped the war effort in the First World War > https://bit.ly/46dNl3r

Great War to Race Riots > https://bit.ly/3F8qYh5