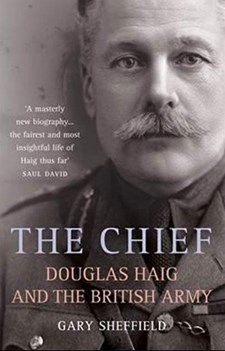

The Chief: Douglas Haig and the British Army

- Home

- World War I Book Reviews

- The Chief: Douglas Haig and the British Army

Reviewed by David Filsell.

In the last four years three new biographies of Douglas Haig have been published. Each, of the works helps mark the fact that the Field Marshal is being seen not as ‘butcher and bungler’ but as a figure of historical importance and deserving of sober unemotional analysis.

Douglas Haig’s post-Great War reputation has followed a sinuous course. From genuine adulation by the British public his standing fell after his early death in 1928. By then disillusionment about the war was already firmly established. John Terraine’s, then highly controversial, evaluation of the Field Marshal (Douglas Haig: The Educated Soldier, 1963) offered the first scholarly and positive reevaluation of Haig the man and the soldier.

Gary Sheffield, Haig’s latest biographer is uniquely qualified. As an academic he has been in the van of those re-examining and exposing the BEF’s development and improvement as a fighting force. The author has written a number of well-regarded books, including Forgotten Victory: The First World War: Myths and Realities (Headline 2001) in which he deployed some of he arguments which he expands on in The Chief. Sheffield was co-editor, with John Bourne, of Douglas Haig: War Diaries and letters 1914 - 1918 (2006). He shows command of sources - primary and secondary – newspapers, document collections and articles. The Chief is well-written. Sound narrative drive leads the reader through Haig’s life and military career and his development as a soldier and leader. It shows both that which influenced Haig and his own influence on the development of the British Army before the war, ‘his’ war-time army and the senior commanders who together achieved victory by force of arms in 1918.

This is no hagiography. Haig’s weaknesses are exposed and evaluated. His are examined and evaluated alongside his successes. In showing the development of his command style and his judgement - the good and the poor, the over ambitious planning, the ‘lack of grip’ - and the political and military environment in which he operated. In his evaluation of Haig’s military decisions and thinking, the author makes judgements which seem to have been without preconditions and which evaluate his decisions from the perspective of the period; not that of the early 21st century. The author’s view of Haig is largely positive; even the most blinkered will find it difficult to argue significantly with the author’s overall judgements, even if they pick at the detail. In essence, Sheffield’s view is of a man he considers of ‘true historical significance’. In his assessment of Haig’s command, character and conscience the author highlights the key achievements which he considers outweigh his weaknesses. The author concludes that Douglas Haig played a key role in reforming the army, ensuring its preparedness for war in 1914; made a major contribution toward transforming the BEF into a war-winning force; provided generalship vital to allied victory and, as a leader of ex-servicemen, played a crucial part in ensuring Britain’s political and social stability adding: ‘Douglas Haig might not have been the greatest military figure Britain has ever produced, but he was one of the most significant – and one of the most successful’.

Very highly recommended.

The Chief: Douglas Haig and the British Army

Arum Press, 2011, £25, 460pp, 23 plates, notes and references, bibliog, index.

ISBN 978 1 845134 691 8

By Gary Sheffield