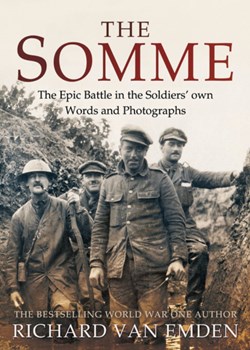

The Somme: The Epic Battle in the Soldiers’ own Words and Photographs

- Home

- World War I Book Reviews

- The Somme: The Epic Battle in the Soldiers’ own Words and Photographs

By Richard van Emden

Pen and Sword, 2016, £20.00 hb, £11.99 pb and £15.00 e–book, 355pp, fully illustrated throughout, index.

ISBN: 9–781– 473–855–21 2

Review by Barbara Taylor

Richard van Emden is an ‘everyman’ author.

He has published many titles that need no repetition here. His work is very popular and it seems that this book is an almost instant bestseller; not surprising in this centenary year of the Somme battle.

The Somme: The Epic Battle in the Soldiers’ own Words and Photographs consists of letters and photographs – the author assuring us that many have never been seen before – and also four pages of sources and permissions and two general maps. The author deals with events in chronological order, not just from the start of the battle on 1 July 1916, but from the time in the summer of 1915 when the BEF took the area over from the French Army.

One of the strengths of this book is the author’s introduction, in which he explains just how these men came to be at war with cameras, often the relatively new Vest Pocket Kodak (VPK).

Photography had become much more accessible to the masses in the years before the war, with the introduction of the ‘vest pocket’ camera. Not really pocket by modern standards – although the dimensions of the VPK were not much different to those of a modern iPhone – but at least amateur photographers no longer had to visit specialist studios or rely on professionals lugging around cameras on tripods with bulky glass plates.

Although the VPK type cameras were relatively inexpensive, at around 30 shillings (£1.50), it has to be said that most of these photographers would have been officers given that the cost would have been beyond the income of the typical working man.

Soon after the war started, the photographs taken by these amateurs started to be published in newspapers and magazines; such was the demand for ‘action shots’ as the War Office had not appointed official photographers from the start of hostilities. As these images started to appear, the authorities panicked and the use of cameras on the Western Front was banned. Severe punishments were threatened.

Many men complied and sent cameras home with the re–issuing of this edict during 1915. Fortunately for us, some men ignored the warnings and carried on. Many amateur photographs were annotated on the rear or in albums so that one could identify who the subjects are. The author asserts that many men gave up their cameras because they had become disillusioned as the war descended into unremitting attrition and the sense of adventure and optimism had ebbed away; even more so after the Somme.

Generally I feel that these types of books are ‘lazy’ history, in that they do not include any original research. In spite of that I do like this book because some of the photographs have links to the text, rather than just being a narrative illustrated with stock photographs. Personally I would have liked to have seen see a few more linking pieces, but at least the author allows the officers and men to tell the story of the battle as it unfolded and as they saw it at the time. Finally I must applaud Pen and Sword for the quality of paper this volume is printed on. A big improvement and a trend that they need to persevere with.

[This book review first appeared in the Western Front Association journal Stand To! 108]