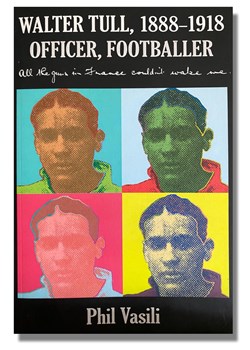

Walter Tull, 1888-1918 Officer, Footballer by Phil Vasili

- Home

- World War I Book Reviews

- Walter Tull, 1888-1918 Officer, Footballer by Phil Vasili

Paperback 256 Pages

Published: 11/11/2009

Publisher: Raw Press

ISBN: 9780956395405

I'm dividing this review of 'Walter Tull, 1888-1918 Officer, Footballer' into four parts: the chronology, the storytelling, additional insights and editorial matters.

The Chronology of Walter Tull's Story

Walter Tull was black and British, born in Folkestone to a Jamaican immigrant carpenter and a local girl. He was one of five children. His story has multiple layers from his genteel, hard working class Methodist roots in Folkestone to his experience as an orphan being raised in a London home, through success as a football player and his short career in the army during the First World War as a Private, then as an Officer. Vasili is thorough with the spine of the story, though occasionally he does indulge a topic or person that is 'out on the limb' - the story of Walter's older brother Edward, who shared the orphanage experience and was then adopted makes sense, though the stories of other black footballers and athletes who served in the Great War hints at a future book; it is too easy to disappear down the proverbial research 'rabbit hole' to see where an idea might go or to see how it unfolds to see where experiences differ or not - here a firmer editorial hand would have been of value. What works well are the stories and details of Tull's experiences with the detail of his football and army careers given equal attention. In fact, his progress through football teams is matched by his subsequent progress in the army, from the ranks to officer, from the Western Front to the Italian Front, from Messines and Pilkem Ridge to the Montello Sector on the River Pave. The many raids Tull led show his nerve and skill at leading men and they are as fascinating in the telling as any tight game of First Division football. Later when Tull is back on the Western Front we feel the pending doom of the heavy bombardment at Gommecourt. The efforts to retrieve the body by Pte. Tom Billingham, a former Leicester Fosse goalkeeper, feels like an ending too fitting to be true.

On the other hand, dropping in a few lines to explain that Tull's CO's son went to Hollywood after the war and was one of Marilyn Monroe's lovers leaves this reader thinking 'so what' - once again, the lack of editorial input is telling. Perhaps Prof. David Killingray could have done more than read an early draft and have provided editorial input.

The Story of Walter Tull

The manner in which Walter and his siblings became orphans is revealing and not unusual at the turn of the last century - their mother was lost to breast cancer, and their father to heart disease leaving six children with their young step-mother who in turn remarried and had further children of her own. Their circumstances were perilous which is where contacts through their church could step in. What the story ultimately reveals is that of more impact on Tull’s life than his colour was his becoming an orphan while a young boy and being raised in a Methodist orphanage which provided him with stability and a sound education, which allowed him to developed self-control and exposed him to competitive sport.

Additional Insights on Walter Tull and Black Footballers of the early 20th century

Vasili is thoughtful, sympathetic and honest. The overall impression you get is that is Walter's 'muscular Christianity' of his Methodist upbringing and outlook, the cloistered education and footballing success was neither helped or hindered (for most of the time) by his mixed ethnicity. Indeed, one has to wonder how much more has been made of him since the First World War because he was that rare thing - a black officer in the British Officer who led his men. Given the circumstances little else about him was exceptional - his Britishness meant that he could fit in with ease despite his colour where those black men not born and raised in Britain could not. As Vasili insightfully points out regarding Walter's brother Edward's acceptance as an educated dentist playing golf in the very white domain of Scottish golf much of this had to do with 'cultural assets: his profession, education and religious beliefs and the friends and contacts made and fostered in those overlapping universes ...' (p.19)

The author’s voice and views only appear from time to time talking about the journey taken during his research with reflections on the way, which can add and at other times detract, whether this is making comparisons to the Falkland War, Iraq War, Afghan War and the Nazis, or the machinations of contemporary footballer Ronaldo, Sepp Blatter and the notion of the 'brat football player' or comparisons to the film Chariots of Fire: some conclusions are best left to the reader. And is this the right place to look at the lot of black sportsmen in cricket and boxing? That said, I love the quote from The Illustrated and Dramatic News (4 November 1899) that 'War is a sport, and, like every other sport except croquet, has its moral side ... '

The question of recruitment across Britain and its Empire is well covered and frequently revisited; it can only be conjecture to suggest why a man enlisted as a volunteer at a particular time. Vasili correctly picks out a sense of duty, peer pressure and a sense of social debt as reasons to enlist. Other reasons should include the torrent of news coverage, propaganda, social and economic pressure while in due course, men such as Frank Dove were called up 'compulsorily'.

The full story of why someone who was black, not of 'European birth' was or was not accepted is yet to be fully researched and told; Vasili makes a healthy start at this process, that issues of racism, colour, shades of black or brown, education, sporting prowess and assimilation into British society and so on all had a role to play. Circumstances where a person enlisted differed greatly; a man enlisting with his friends and colleagues in a group, especially a recognised footballer, would be hard to turn down - others got through in this way, whether of African or Asian descent because the recruiting officer otherwise risked loosing an entire group. We also know that the well-connected, educated and wealthy sons of Maharajas or merchants educated in Britain, and especially if they have the clout of an Oxbridge College behind them, might find themselves in the ranks or even the officers' mess whilst men disembarking from ships from the Caribbean trying to enlist in Cardiff or Newport in early September 1914, by way of example, were turned away. It is certainly a subject worthy of further research.

Editorial strengths and weakness of Walter Tull

Walter Tull is written by an enthusiast, not academic or journalist - this lends it more charm, the research journey and the quest to track down relatives is part of the story. Where some assistance is required is where historic events are left to the biased opinions of just one or two commentators, for example quoting the 1950s/60s author and playwright Alan Sillitoe who wrote about the 'horrific cull of young British men' during the First World War is verging on a 'donkeys' view of the generals; our interpretation of events of 1914-1918 are somewhat more nuanced today. This could have been picked up through sharper editorial guidance, while the suggestion that boarding institutions such as boarding schools and orphanages could induce homosexuality is ill considered - this from a reviewer who not only attended such institutions from the age of 7 years 11 months to 16 years and 10 months but has made it something of a study topic these last few decades. British boarding schools had more in common with orphanages and Borstals than the parents of the boys like to be told - homosexuality was no greater than in the general population and has been hidden and unmentioned until recently.

Throughout there is a nervousness about calling a person white or black - simple defining adjectives which for some unknown reason are capitalised in every instance. This should also have been picked up by the editor not least because much of the history of race and ethnicity over the last 100 years had been to downplay racial differences as defined by colour. To quote Press Guidelines, 'Black and white are adjectives that should be used (in lowercase only unless they begin a sentence) to modify nouns, such as "black Americans" or "black men" or "white women." Once again, an experienced editor would have been of great assistance here. We are also provided with a few pages on Indian officers in the Army and RAF - this, as they say, opens up 'another can of worms', not least that black refers to a person of African descent while brown generally refers to those of an Asian background. Of course, the entire conversation around skin colour, tones and shades, is a difficult one - unless you are a racist South African General who pre-apartheid would define a person by race and mixed ethnicity. Such a general was CO for the BWIR with brutal consequences revealing how those of Caribbean or West Indian heritage were thought of as different to black men from tribal groups in southern Africa.

There is no doubt that Walter Tull deserves this attention of a book, podcasts and documentaries - he was a good person, who worked hard, took his chances and had the respect and friendship of those around him. The one spoiler in his life, is an episode of foul racist name calling and chants during a football game - this deserves greater attention as it was clearly . In all fairness to Phil Vasili the entire question of the history of race relations at the time of Empire and during the First World War would require a substantial thesis of their own. The criteria for recruits to be of ‘pure European descent’ was sometimes ignored when the person in question was raised in Britain or a highly educated doctor or from the Indian aristocracy (though not always) while immigrant labourers from the Caribbean or illiterate men from South Africa tribes lacked the additional compensatory credentials. Other texts detail how and when black men of the British Empire served as combat soldiers in the West Indian Regiments or in the labour corps. The stories of race riots after the war deserve telling, indeed the entire aftermath of the world war, the European component of which ended in 1918, is poorly understood.

There is both insight and anecdote, such as the supposed derivation of the expression ‘sick as a parrot’ from the time when a club mascot, a parrot brought from Argentina while on a football tour, used as a fancy dress prop in which Walter Tull played ‘Man Friday’ to a fellow players ‘Robinson Crusoe’ later died on the day Spurs was relegated from the First Division.

There is more than one biography on Walter Tull; this is by far the best. What is more, it comes with a wide and unique selection of photographs and endorsement from the granddaughter and niece who contributed to it. The chronology of Walter’s life is full and sound, the storytelling sweeps you along and whilst there are a few too many additional factoids and author’s thoughts that could have been addressed in other ways through firmer editorial guidance these will be developed in future publications. Vignettes are given of a black vet, a black doctor, stowaways from the Caribbean, and other black British born men who served or were turned away because of their colour, or prevented from becoming an officer as not being of 'European descent' - all of these might have best been kept to an appendix, or for another book (which I believe is the case). With no or few copies of Walter Tull, 1888-1918 currently available perhaps a second edition could address some of the issues mentioned above. Until then, it remains the best book on Walter Tull.

Further links: Phil Vasili

Review by Jonathan Vernon (Digital Editor) and Co-Chair of Black History Month, Lewes.