Winged Victory by Victor M. Yeates

- Home

- World War I Book Reviews

- Winged Victory by Victor M. Yeates

I’d heard there was a book written about flying in the First World War that was in great demand by flyers in the Second; this was ‘Winged Victory’ by Victor Yeates who had died of TB in 1934. Out of print, rare copies were going for £5 each in 1941 (over £200 today). Its rarity is part of the story: published in 1931 the interest in novelisations of first hand accounts of the First World War had waned - yet it is a good read, a great read, a profoundly revealing, touching, vivid and thoughtful read. T.E.Lawrence ‘one of the most distinguished histories of the war’. Cecil (1995 p.42/43). Cecil compares it to All Quiet on the Western Front - perhaps it is better. There is little fiction or contrived dramatic structure in Winged Victory.

My journey to Winged Victory comes via Hugh Cecil’s ‘The Flower of Battle’ in which he takes a dozen of the less known fictionalised accounts of the First World War and expounds their virtues. Cecil calls Winged Victory ‘a tough, cheeky, vital, unhappy book which falls emphatically into the ‘disenchanted’ school for war literature’. Cecil, (1995, p.43) Reading Winged Victory for the first time in 2022 I found it exhilarating, at first celebratory about the thrill of flying and the wonder of the sky in all weathers. It is the relentless exposure to danger that wears the protagonist down and leads him to drunkenness, cynicism and depression.

Top Gun: Maverick was on at our local cinema, The Depot, Lewes. The night before we watched the Tony Scott original. The new film was less cheesy, Tom Cruise less full of himself and the flying spellbinding and vertigo-inducing. Let’s not dwell on the clumsy plot that was a direct ripoff from the original Star Wars (1977). I mention this because it is recalling what had been said about Winged Victory that had me take it from the shelf and start to read. The dogfights and other antics and calamities that take place once airborne in a Sopwith Camel are truly captivating, vivid with their description and anxiety creating as disaster is only averted because of an intimate knowledge of flying, the state and control of a fickle engine and the limitations of the plane. I found many of the sequences as exciting as Top Gun. The comparison even goes as far as bravado and drink-fuelled behaviour of young men in the mess, or out on the town - though Winged Victory has far more authenticity and is set in the context of a real, not an invented war.

The detail is such that you assume the author is writing from a diary; you understand from Cecil that unwell with TB Victor Yeates was emptying his heart and soul into the text and recalling the minutest detail, thoughts, feelings and conversations of the six or seven months in 1918 when he saw active service with No.46 Squadron on the Western Front.

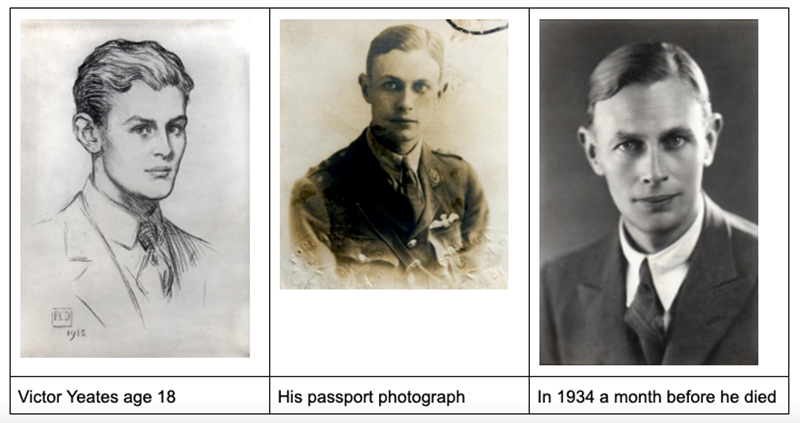

Victor Yeates was born on 30 September 1897. He came from humble origins, his father was a bank clerk. A small family, he had a far older sister and that is all. They lived at 68 Granville Park, Blackheath. Victor went to school at the grammar school in Lewisham where he and his great friend Henry Williamson (the author of Tarka the Otter) were consigned to the class for ‘slackers, leaving school at 16 to find work rather than fulfilling their initial intellectual promise.

Born in 1897, Victor was bound to enlist or be conscripted and thus it was in February 1916 that he joined the Inns of Court OTC. The following year he married Norah Phelps - five years his senior, at St.Martin’s, Ruislip. He transferred to the RFC 5 May 1917. He trained on the Maurice Farman Shorthorn and Avro 504k. Despite the significant shortcomings of these machines he found flying exhilarating.

In that passionless bright void, joy abode, interfused among cold atoms of the air. Breath there was keen delight, all earthly grossness purged.

He raced over the craggy plain, now dropping into glens, now zooming up slopes, leaping over ridges, wheeling round tors. Sometimes he could not avoid a sudden escarpment, and hurtled against the solid-seeming wall that menaced him with destruction: he would hit it with a shockless crash that expunged the wide universe; but in a flash it was recreated after a second of engulfing greyness. And when he had played long enough in the sky gardens, he would land on a suitable cloud. He throttled down and glided into the wind along the cloud surface, pulling the stick back to hold off and get his tail down. He settled down on the surface that looked solid enough to support him, but it engulfed him as he stalled, and the nose dropped with a lurch into the darkness and almost at once he was looking at the collied world of fields and trees and roads. Cecil (1985, p.48)

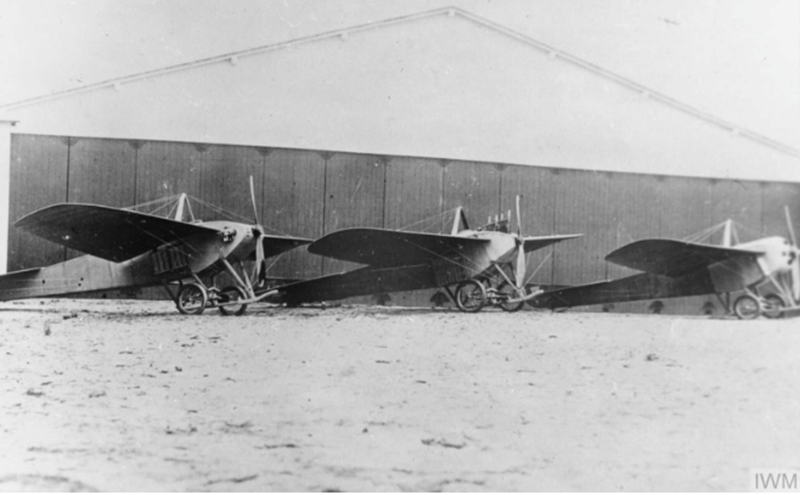

Having survived, many did not, he moved on to the Sopwith Pup and then the Sopwith Camel. Training complete by February 1918 with a commendable 52 hours flying time he joined No.46 Squadron RAF in France. He went on to take part in 18 big air battles. During his sojourn he had four crashes (twice caused by engine problems and twice having been shot down). In another pilot's hands any of these and many, many other incidents could have been fatal. Indeed, death could be horrible ‘frying alive for at least a minute’ in a flaming spin. So it is no wonder that riotous parties filled with whisky and champagne were commonplace. What is enlightening about Yeates though is that flying is put in context, the rhythm of the day, across the seasons, is forever curtailed by the state of the weather. There were many quiet periods, time for endless conversations - “Either, ‘shop’ or in Yeates' case, arguments about life, women and the war’. Cecil (1995 p.52)

Hugh Cecil’s chapter on Victor Yeates provided a potted history of Henry Williamson too. It is clear that Winged Victory would not have been written had Williamson not cajoled and encouraged Yeates into action, that he set up the simple theme of the relationship between two pilots - friends together in arms and fatigue caused by prolonged war, and that his advice, proofreading and some rewriting of the final chapter was invaluable. However, Williamson was never a co-author as he later claimed - Yeates listened to and ignored suggestions to edit heavily or to weave in other contrivances of plot, preferring to adhere to a closer and more authentic account.

Tom Cudnall, the protagonist of Winged Victory, like the author himself, trained on a ‘Rumpty’: a Maurice Farman Shorthorn, which Yeates describes as ‘like an assemblage of birdcages’. Yeates (1961, p.84)

On the few occasions Yeates had leave, or later on once he was on sick leave, he found himself being asked the same questions in relation to flying: ‘Why did he take it up?’, ‘What did it feel like the first time in the air?’, and ‘Had he looped the loop?’. Winged Victory more than answers each of these questions, and much more besides. Some of the scene setting and descriptions of dog fights or escaping from a spin or dealing with a faulty engine are so vivid they read like a screenplay.

Yeates writes of ‘flying with their antiquated controls was a mixture of playing a harmonium, working the village pump, and sculling a boat’. Yeates (1961, p.84)

We learn, in much detail, about the training a pilot received at this time, of his first (inevitable) crash and first spin (either of which could have been fatal). And in passages like the following we learn exactly how an engine was started and a aeroplane taxied and became airborne.

Exact routine of starting an engine in a Sopwith Camel (p.18/19)

Tom settled into his seat, and a mechanic called out "Switch off, petrol on'. Tom answered with the same words, and pumped up pressure, fastened his safety belt, waggled the joystick, kicked the rudder bar, and pulled up the CC gear piston handle, while they turned the engine

backwards to suck in gas. He gave his goggles a rub up with his handkerchief. ‘Contact' shouted the mechanic, and Tom switched on and answered 'Contact The engine started at the first swing. He eased the throttle back and adjusted the petrol flow until it was ticking over. His goggles were misty and he gave them another rub. They would clear after a little. Looking round he saw Mac taxiing out to take off. Miller was following. Tom opened out with a roar, looked at the rev counter, throttled down, and waved his hand. The mechanics pulled away the chocks from the wheels of the undercarriage, and ran round to the rear of the planes to hold the rear struts in order to help him turn.

He swung round and opened out at once. The effell, as the thing was called that showed wind direction, was hanging limp; so he could take off in any direction that gave a clear run.

The grey morning air was as still as cream, and the dizzy ground fled by, leaving him in utter stillness except for engine vibration. He held the Camel's nose down to gain speed, and then pushed the stick over to the left as he let it zoom, doing a steep left-hand climbing turn, his wing-tip almost brushing the ground, and it leapt up with glorious release over the trees that surrounded the mess.

He flattened out, and then put up its nose to climb until the whole machine was shuddering with the strain. He knew what it could do, and kept it there until the aerodrome had become a little lawn and Izel a village in Lilliput.

Cudnall took risks, because he enjoyed flying and putting on a show, even if it meant harrying those on the ground with his low flying antics. He had a sense of humour, a satirical wit regarding the war and how it was being conducted. He drank alcohol to excess, increasingly to bury his thoughts and fears. Over time, like an alcoholic he seeks frequent solace in binge drinking to the point of becoming violently ill and incapable of flying - though it would appear he only went up once when drunk. Stoicism turns to a kind of pacifism regarding the impact of the war on the land around him.

‘The desolation of the dead land below them seemed to impregnate the atmosphere with gloom and horror, exhaling contagion that defiled the air and tainted the clouds with death and corruption’.Yeates, 1916 (p.138)

There is talk of heroism, leadership, camaraderie, risk taking, getting the job done, the ethics of war, and living for the moment - enjoying booze and birds with the occasional dalliance with young women and prostitutes.

“A leader should be enthusiastic, bloody-minded, courageous, cunning, a dead shot, a real pilot, a tree leopard, a buffalo, an eagle, a steel-gutter killer’. Yeates (1961, pp.353/354)

Compared to some authors of the time which are riddle with deletions, only a couple of times is the word ‘fuck’ replaced with a dash. He becomes sick of the killing, dwelling two much on the men in the machines he shot down to the point of dodging ‘the kill’ and so risking himself and others.

He describes a dogfight to the death (p.252)

"Mac went straight down on one of them. Tom, on his left, was in position to attack the other, and he veered to get it in his Aldis. He opened fire and the observer replied. He found himself in the unenviable position of fighting a two-seater single-handed, as all the others had followed Mac. The observer was doing some good shooting, and Tom had to sideslip away. He dived, still sideslipping, for position under the LVG's tail. The pilot saw him, and turned steeply to keep him in the observer's field of fire. He could out-fly the two-seater, but it was extremely difficult to do so with the observer's tracer coming so near. He had to sideslip and twist so much that he could not make effective reply, but he fired whenever his nose was pointing near the enemy, to put the wind up the pilot. After one of these bursts the LVG reversed bank as quickly as it could and in doing so put Tom in the observer's blind spot, and he was able to fire a more dangerous burst, and this was more than the pilot could stand. He put his nose down to dive away. At the same moment two other Camels came up and fired, and all four aeroplanes went careering earthwards. But the LVG was hit vitally: Smoke poured from it, and it hit the earth with a blazing pyre.’" Yeates (1961 p.252)

Slowly fear and depression take over, only countered by a joy of flying and alcohol.

“There had been a glory in bare or cloudy skies: there had been joy in the lifting wings of flight: those things were gone; he had grown suddenly older, and beauty was dumb’. Yeates (1961, p.335)

He is dismissive though regrets the number of new boys to the squadron lost in their first few days, unable to handle an engine problem or caught and shot out of the sky, purely for lack of experience. Survive a few weeks and they might just serve a few months, was the thinking.

We come to know the everyday experience of the RAF fighter pilot, their thoughts, concerns and conversations, meeting different characters, many of whom ‘go west’. We learn a good deal about aeroplane too - and behaviour of the enemy on the ground and in the air.

War weary (p.360)

‘The blood feud of the nations would go on from war to war, from horror to horror ‘till the world was one great shambles. They called this the war to end war; so men were encouraged to fight on’. (p.455)

He became war weary. His dreams kept him awake. He became terrified of getting into a scrap in the air and having to kill anyone again, whether in a fair fight in the air, or low-level bombing or gunning troops and machine gunners.

His final view was pessimistic.

‘He had opened a rift in the boundary of the human world, and beyond it there was lightless chaos’. Yeates (1961 p.455) and his last lines, reflecting on the train from Folkestone after seven months in France, was nihilistic: ‘This was England: wandering lanes, hedged and ditched. Casual, opulent beauty, trees heavy with fulfilment. This was his native land. He did not care’. Yeates, (1961 p.456)

Review by Jonathan Vernon

References

Cecil, H (1995) The Flower of Battle: British Fiction Writers of the First World War. Secker & Warburg

Yeates, V.M. (1961) Winged Victory. Jonathan Cape.

Resources and links: