The Historic Christmas Truce of 1914 by Capt Sir Edward Hulse, Bart

- Home

- Latest News

- 2024

- December 2024

- The Historic Christmas Truce of 1914 by Capt Sir Edward Hulse, Bart

Despite the bitter fighting which had been going on for over four months, a remarkable armistice was observed in many sectors on Christmas Day 1914, and English and German soldiers ceased killing each other for one day and fraternized in a most genuine manner. In the following passage a Captain of the Scots Guards describes the extraordinary scenes enacted between the lines during this highly unofficial truce. The author held a regular commission in the Scots Guards in 1914. He was killed in action on 12 March 1915 aged 25 whilst going to the aid of his severely wounded Commanding Officer, Major George Paynter whose name crops up in the following account.

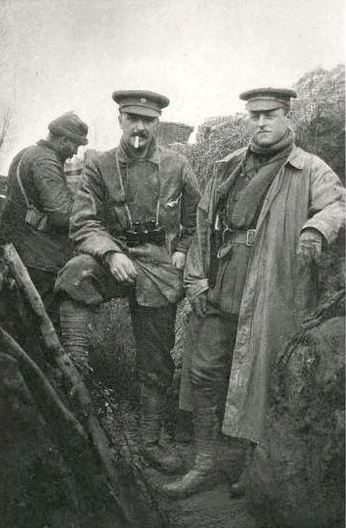

Above: Capt Sir Edward Hulse. Killed in March 1915, he is buried in Rue-David Military Cemetery. The narrative below was published in 'I Was There!' part 7 just prior to the outbreak of the Second World War.

The following passage has been superbly narrated as part of our I Was There! series by Bryan Jaram. It can be seen on our YouTube channel via this link: The Historic Christmas Truce of 1914 by Capt Sir Edward Hulse, Bart

On the 23rd we took over the trenches in the ordinary manner, relieving the Grenadiers, and during the 24th the usual firing took place, and sniping was pretty brisk. We stood to arms as usual at 6.30a.m. on the 25th, and I noticed that there was not much shooting; this gradually died down, and by 8 a.m. there was no shooting at all, except for a few shots on our left (Border Regiment). At 8.30 am I was looking out, and saw four Germans leave their trenches and come towards us; I told two of my men to go and meet them, unarmed (as the Germans were unarmed), and to see that they did not pass the half-way line.

We were 350 to 400 yards apart at this point. My fellows were not very keen, not knowing what was up, so I went out alone, and met Barry, one of our ensigns, also coming out from another part of the line. By the time we got to them they were three-quarters of the way over, and much too near our barbed wire, so I moved them back.

They were three private soldiers and a stretcher-bearer, and their spokesman started off by saying that he thought it only right to come over and wish us a Happy Christmas, and trusted us implicitly to keep the truce. He came from Suffolk, where he had left his best girl and a 3h.p. motorbike! He told me that he could not get a letter to the girl, and wanted to send one through me. I made him write out a postcard in front of me, in English, and I sent it off that night. I told him that she probably would not be a bit keen to see him again. We then entered on a long discussion on every sort of thing. I was dressed in an old stocking - cap and a man's overcoat, and they took me for a corporal, a thing which I did not discourage, as I had an eye to going as near their lines as possible.... I asked them what orders they had from their

officers as to coming over to us, and they said none; they had just come over out of goodwill.

They protested that they had no feeling of enmity towards us at all, but that everything lay with their authorities, and that being soldiers they had to obey. I believe they were speaking the truth when they said this, and that they never wished to fire a shot again. They said that unless directly ordered they were not going to shoot again until we did. . . . We talked about the ghastly wounds made by rifle bullets, and we both agreed that neither of us used dum-dum bullets, and that the wounds are solely inflicted by the high-velocity bullet with the sharp nose, at short range. We both agreed that it would be far better if we used the old South African round-nosed bullet, which makes a clean hole . . . .

They think that our Press is to blame in working up feeling against them by publishing false ‘atrocity reports.’ I told them of various sweet little cases which I had seen for myself, and they told me of English prisoners whom they had seen with soft-nosed bullets, and lead bullets with notches cut in the nose. We had a heated and at the same time good-natured argument, and ended by hinting to each other that the other was lying!

I kept it up for half an hour, and then escorted them back as far as their barbed wire, having a jolly good look round all the time, and picking up various little bits of information which I had not had an opportunity of doing under fire! I left instructions with them that if any of them came out later they must not come over the half-way line, and appointed a ditch as the meeting place. We parted after an exchange of Albany cigarettes and German cigars, and I went straight to headquarters to report. On my return at 10am, I was surprised to hear a hell of a din going on, and not a single man left in my trenches; they were completely denuded (against my orders), and nothing moved!

I heard strains of ‘Tipperary' floating down the breeze, followed by a tremendous burst of 'Deutschland über Alles,' and as I got to my own company headquarters dug-out I saw, to my amazement, not only a crowd of 150 British and Germans at the half-way house which I had appointed opposite my lines, but six or seven such crowds, all the way down our lines, extending towards the 8th Division on our right.

I bustled out and asked if there were any German officers in my crowd, and the noise died down (as this time I was myself in my own cap and badges of rank).

I found two, but had to talk to them through an interpreter, as they could neither talk English nor French.

I explained to them that strict orders must be maintained as to meeting half way, and everyone unarmed; and we both agreed not to fire until the other did, thereby creating a complete deadlock and armistice (if strictly observed)....

Meanwhile Scots and Huns were fraternizing in the most genuine possible manner. Every sort of souvenir was exchanged, addresses given and received, photos of families shown, etc. One of our fellows offered a German a cigarette; the German said, "Virginian?" Our fellow said, "Aye, straight-cut"; the German said, "No thanks, I only smoke Turkish!" It gave us all a good laugh.

A German N.C.O. with the Iron Cross - gained, he told me, for conspicuous skill in sniping - started his fellows off on some marching tune. When they had done I set the note for 'The Boys of Bonnie Scotland, where the heather and the bluebells grow' and so we went on, singing everything from 'Good King Wenceslas' down to the ordinary Tommies song, and ended up with 'Auld Lang Syne,' which we all, English, Scots, Irish, Prussian, Wurttembergers, etc, joined in. It was absolutely astounding, and if I had seen it on a cinematograph film I should have sworn that it was faked.

Above: Hulse in the trenches in 1914 with Captain Warner (source: Hulse, Edward Hamilton Westrow, Sir, 1889-1915 Letters written from the English front in France between September 1914 and March 1915)

From foul rain and wet the weather had cleared up the night before to a sharp frost, and it was a perfect day, everything white, and the silence seemed extraordinary after the usual din. From all sides birds seemed to arrive, and we hardly ever see a bird generally. Later in the day I fed about fifty sparrows outside my dug-out, which shows how complete the silence and quiet was.

I must say that I was very much impressed with the whole scene, and also, as everyone else, astoundingly relieved by the quiet, and by being able to walk about freely. It is the first time, day or night, that we have heard no guns or rifle-firing since I left Havre and convalescence.

Just after we had finished 'Auld Lang Syne' an old hare started up and, seeing so many of us about in an unwonted spot, did not know which way to go. I gave out one lout ‘View Holloa’ and one and all, British and Germans, rushed about giving chase, slipping up on the frozen plough, falling about, and after a hot two minutes we killed in the open, a German and one of our fellows falling together heavily upon the completely baffled hare. Shortly after wards we saw four more hares and killed one again. Both were good heavy weight, and had evidently been out between the two rows of trenches for the last two months, well fed on the cabbage patches, etc, many of which are untouched on the no-man's-land. The enemy kept one and we kept the other.

It was now 11.30 am, and at this moment George Paynter arrived on the scene with a hearty, “Well, my lads, a merry Christmas to you! This is d---d comic, isn't it?"... George told them that he thought it only right that we should show that we could desist from hostilities on a day which was so important in both countries; and he then said: "Well, my boys, I've brought you over something to celebrate this funny show with." And he produced from his pocket a large bottle of rum (not ration rum, but the proper stuff). One large shout went up, and the nasty little spokesman uncorked it and, in a heavy, ceremonious manner, drank our healths in the name of his "kamaraden”. The bottle was then passed on and polished off before you could say “knife”.

During the afternoon the same extraordinary scene was enacted between the lines, and one of the enemy told me that he was longing to get back to London. I assured him that "So was I." He said that he was sick of the war, and I told him that when the truce was ended any of his friends would be welcome in our trenches, and would be well received, and given a free passage to the Isle of Man!

Another coursing meeting took place, with no result, and at 4.30 p.m. we agreed to keep in our respective trenches, and told them that the truce was ended. They persisted, however, in saying that they were not going to fire, and as George had told us not to unless they did, we prepared for a quiet night, but warned all sentries to be doubly on the alert.

During the day both sides had taken the opportunity of bringing up piles of wood, straw, etc, which is generally only brought up with difficulty under fire. We improved our dug-outs, roofed in new ones and got a lot of useful work done towards increasing our comfort. Directly it was dark I got the whole of my company on to improving and re-making our barbed-wire entanglements all along my front, and had my scouts out in front of the working parties to prevent any surprise. But not a shot was fired, and we finished off a real good obstacle unmolested.

On my left was the bit of ground over which we attacked on the 18th, and here the lines are only from 85 to 100 yards apart.

The Border Regiment were occupying this section on Christmas Day, and Giles Loder, our adjutant, went down there with a party that morning on hearing of the friendly demonstrations in front of my company, to see if he could come to an agreement about our dead, who were still lying out between the trenches. The trenches are close at this point that, of course, each side had to be far stricter. Well, he found an extremely pleasant and superior stamp of German officer, who arranged to bring all our dead to the half-way line. We took them over there and buried 29 exactly half-way between the two lines. Giles collected all personal effects, pay-books and identity discs, but was stopped by the Germans when he told some men to bring in the rifles. All rifles lying on their side of the half-way line they kept carefully...

They apparently treated our prisoners well and did all they could for our wounded. This officer kept on pointing to our dead and saying, “Les braves, c'est bien dommage…"

When George heard of it he went down to that section and talked to the nice officer and gave him a scarf. That same evening a German orderly came to the half-way line and brought a pair of warm, woolly gloves as a present in return for George.

The same night the Borderers and we were engaged in putting up big trestle obstacles, with barbed wire all over them, and connecting them, and at this same point (namely, where we were only 85 yards apart) the Germans came out and sat on their parapet and watched us doing it, although we had informed them that the truce was ended.... Well, all was quiet, as I said, that night; and next morning, while I was having breakfast, one of my N.C.O.'s came and reported that the enemy were again coming over to talk. I had given full instructions, and none of my men was allowed out of the trenches to talk to the enemy. I had also told the N.C.O. of an advanced post which I have up a ditch to go out with two men, unarmed; if any of the enemy came over, to see that they did not cross the half - way line, and to engage them in pleasant conversation. So I went out, and found the same lot as the day before; they told me again that they had no intention of firing, and wished the truce to continue. I had instructions not to fire till the enemy did; I told them; and so the same comic form of temporary truce continued on the 26th, and again at 4.30 p.m. I informed them that the truce was at an end. We had sent them over some plum-puddings, and they thanked us heartily for them and retired again, the only difference being that instead of all my men being out in the no-man's-land, one N.C.O. and two men only were allowed out, and the enemy therefore sent fewer.

Few incidents in modern warfare have been more strange or more moving than the spontaneous and quite unofficial Armistice of Christmas 1914 which Sir Edward Hulse describes in this passage. It was not only in his sector that this memorable fraternization took place. The two photographs above and below show British officers in the Bridoux - Rouges Bancs Sector, with their temporary German friends in no-man's- land. Both photographs show the remarkable divergence between the uniforms of British and German officers and other ranks.

Again both sides had been improving their comfort during the day, and again at night I continued on my barbed wire and finished it right off. We retired for the night all quiet, and were rudely awakened at 11 p.m. A headquarters orderly burst into my dug-out and handed me a message. It stated that a deserter had come into the 8th Division lines and stated that the whole German line was going to attack at 12.15 midnight, and that we were to stand to arms immediately, and that reinforcements were being hurried up from billets in rear. I thought, at the time, that it was d---d good joke on the part of the German deserter to deprive us of our sleep, and so it turned out to be. I stood my company to arms, made a few extra dispositions, gave out all instructions, and at 11.20 p.m. George arrived…

The ‘gentleman's agreement’ not to fire during the Christmas Armistice did not forbid preparing for the time when the temporary peace must end. Here, at Rue de Bois, men of a Highland regiment are putting in part of Christmas Day constructing a breastwork of mud and hurdles. They are in full sight of the German line in the trees on the left, but not a shot was fired, and Sir Edward Hulse describes in this page how he saw Germans sitting on the parapet of their trenches, indifferent spectators.

Suddenly our guns all along the line opened a heavy fire, and all the enemy did was to reply with 9-inch shell (heavy howitzers), not one of which exploded, just on my left. Never a rifle shot was fired by either side (except right away down in the 8th Division), and at 2.30 a.m. we turned in half the men to sleep and kept the other half awake on sentry.

To the men just down from the line after holding trenches a barn like this was luxury indeed. The roof is rainproof, the icy winds cannot penetrate the walls, and there is ample straw for bedding. This barn, occupied by the Scots Guards in December, 1914, was on the road near Sailly-sur-Lys. Later on in the war it was crowded, but not with soldiers resting, for concert parties gave their entertainments here to the most appreciative audiences that ever witnessed a show

On Christmas Day 1914, as described in this passage, there was real Christmas weather in Flanders. Beneath a clear sky fields and trees were decked with hoar-frost. Here, as seen in this remarkable photograph, during that memorable peace meeting of friend and foe, a party of British and German soldiers have forgotten the war, with all its horrors and hardships, for a few all-too-brief hours.

Apparently this deserter had also reported that strong German reinforcements had been brought up, and named a place just in rear of their lines, where, he said, two regiments were in billets, that had just been brought up. Our guns were informed, and plastered the place well when they opened fire (as I mentioned). The long and short of it was that absolutely nixt happened, and after a sleepless night I turned in at 4.30 am, and was woken again at 6.30, when we always stand to arms before daylight. I was going to have another sleep at 8 a.m. when I found that the enemy were again coming over to talk to us (December 27). I watched my N.C.O. and two men go out from the advanced post to meet them, and hearing shouts of laughter from the little party when they met in front, I again went out myself.

They asked me what we were up to during the night, and told me that they had stood to arms all night and thought we were going to attack them when they heard our heavy shelling; also that our guns had done a lot of damage and knocked out a lot of their men in billets.

I told them that a deserter of theirs had only him to thank for any damage done, come over to us, and that they had and that we, after a sleepless night, were not best pleased with him either! They assured me that they had heard nothing of an attack, and I fully believed them, as it is inconceivable that they would have allowed us to put up the formidable obstacles (which we had on the two previous nights) if they had contemplated an offensive movement.

Anyhow, if it had ever existed, the plan had miscarried, as no attack was developed on any part of our line, and here were these fellows still protesting that there was a truce, although I told them that it had ceased the evening before.

So I kept to the same arrangement, namely, that my N.C.O. and two men should meet them half-way, and strict orders were given that no other man was to leave the lines. I admit that the whole thing beat me absolutely. In the evening we were relieved by the Grenadiers, quite openly (not crawling about on all fours as usual), and we handed on our instructions to the Grenadiers in case the enemy still wished to pay visits.

Above: I Was There! part seven, which includes the account of the Christmas Truce reproduced above.

The above is an extract from the account originally published in 'I Was There!' which are being re-interpreted by WFA volunteers from the original publications. These original publications are available for members to view on the WFA's 'Searchable Magazine Archive'.

Further reading(1): A Sobering Aspect of the Christmas Truce: 25 December 1915 by Jill Stewart

Further reading(2): The original source used by the producers of 'I Was There!' in 1939 is almost certainly Hulse's published letters, which can be found here: Letters written from the English front in France between September 1914 and March 1915

Watch a 1968 interview here: The war, for that moment, came to a standstill

Sir Edward Hamilton Westrow Hulse, Bt., was the only child of Sir Edward Henry Hulse, Bt., of Breamore House, Hants, and the Hon. Lady Hulse, only daughter of the first Lord Burnham. He was born at 26 Upper Brook St., Westminster, on August 3rd, 1889, and was christened at Breamore. He succeeded his father in 1903. As a child he attended Mr. Marcon’s school at Beaconsfield, and afterwards went to Mr. A. Max-Wilkinson’s at Warren Hill, Eastbourne, Sussex. In 1903 he entered Mr. R. S. Kindersley’s house at Eton, and afterwards matriculated at Balliol College, Oxford, in 1907, taking his degree in 1912.

After a period of training with the Coldstream Guards, he was given a commission in the 1st Battn. Scots Guards on March 8th, 1913, and went to the front at Mons with it in August 1914. In November he was transferred to the 2nd Battn., and remained in it until his death.

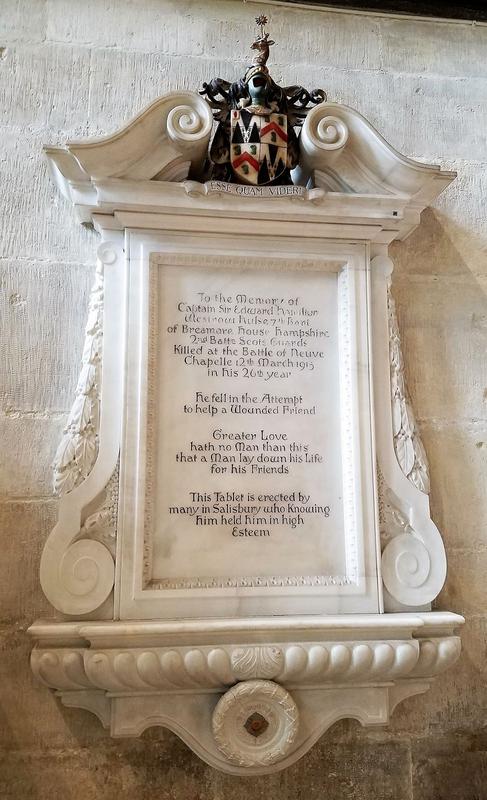

Captain Sir Edward Hulse was killed at Neuve Chapelle on March 12th, 1915, and a tablet recording the manner of his death was put up to his memory in the Cathedral by the citizens of Salisbury. This tablet was dedicated by the Bishop of Salisbury on March 11th, 1916.

Above: The memorial to Edward Hulse at Salisbury Cathedral. © Daniela Cäsar (WMR-43632)