A Sobering Aspect of the Christmas Truce : 25 December 1915

- Home

- World War I Articles

- A Sobering Aspect of the Christmas Truce : 25 December 1915

Many of the accounts of the Christmas ‘Truce’ in 1914 focus on the exchange of gifts and the supposed playing of football…but in at least one instance, there was a more serious and sobering aspect to the fraternisation that took place.

Above: British and German officers meeting in No-Man's Land during the unofficial truce. (British troops from the Northumberland Hussars, 7th Division, Bridoux-Rouge Banc Sector). © IWM Q 50721

On the Fromelles-Sailly Road near Fleurbaix in France, the 2 Scots Guards had taken part in an attack on German trenches at Rouges Bancs on 18 December 1914

‘The attack was timed for 6pm. It was arranged that at 6pm the men should be posted over the parapet and to crawl out under the wire fence and lie down. When this was done, I was to blow my whistle and the line was then to move forward together and walk as far as they could until the Germans opened fire and then rush the front line trenches. Having reached the trench I was to try and hold it if occupied and if unoccupied, to push on to the second line……I blew my whistle as loud as I could, but owing to the noise of our gunfire it appears that it was not generally heard. ..I could see that in several places the line was not being maintained, some men moving forward faster than others….We bayonetted and killed all the Germans we could see in the trench and then jumped down into it. There was a certain amount of shouting and confusion…..’

During the course of the early morning of 19 December, it became clear that the trench had only been taken in places by the Scots Guards, and also that the attack by the 2 Border Regiment had failed. The decision was taken not to send reinforcements and later that morning, the Scots Guards withdrew. The War Diary commented that

‘The cross fire from well-placed German machine guns played a big part, and this accounts for our very heavy casualties amounting to nearly 50% about 180 men being killed or wounded…. ‘

The Battalion’s War Diary identified that Captain H. Taylor and Lieutenant Hanbury-Tracey had been killed, with Lieutenant Nugent missing, believed killed. Although the war diary does not mention the number of other ranks, CWGC information suggests that 100 other ranks were killed in the period 18 and 19 December 1914.

In the days following the attack, the battalion were in billets at Sailly but returned to the trenches on 23 December. On Christmas Eve, the War Diary noted that the trenches opposite ‘were lit up with lanterns and there were sounds of singing’. In an incredibly detailed account of the events at this time, the War Diary then recounts how a scout went out to meet a German patrol. He was given a glass of whisky and a message was sent back ‘saying that if we didn’t fire at them, they would not fire at us’.

Overnight, the guns were silent and on Christmas morning 1914, the War Diary recounts that

‘...a party of Germans came over to our wire fence and a party from our trenches went out to meet them. They appeared to be most amicable and exchanged souvenirs, cap badges etc. Our men gave them plum puddings which they much appreciated’.

Further down the line, the War Diary noted that they were able to make arrangements to bury the dead who had been killed on Dec18/19 and who were still lying between the trenches, the Germans bringing the bodies to a half-way line. Thereafter,

‘Detachments of British and Germans formed in line and a German and English Chaplain read some prayers alternately. The whole of this was done in great solemnity and reverence. It was heartrending to see some of the chaps one knew so well and who had started out in such good spirits on 18 December lying there dead, and some with terrible wounds due to the explosive action of the high velocity bullet at short range’.

One of those to be buried at this time was Captain Hugh Taylor whose body was carried to the Rue-Petillon to be buried. (The entry for him in Bond of Sacrifice states that he was buried in La Cardoniere Farm Cemetery.)

Above: Captain Talyor's original grave

The CWGC records that he is buried in Le Trou Aid Post Cemetery.

Above and below, Le Trou Aid Post Cemetery.

The War Diary went on to record that during the truce on Christmas Day

‘…A German Officer, a middle aged man, tall well set up and good looking, told me that Lt Hon Hanbury-Tracy had been taken into their trenches very seriously wounded. He died after two days in the local hospital and was buried in the German Cemetery at Fromelles. He also said that another young officer had been buried…We think this would be Lieutenant Nugent who was reported missing. Captain Paynter gave the officer a scarf and in exchange an orderly presented him with a pair of gloves….Another officer who could not speak English or French appeared to want to express his feelings, pointed to the dead and reverently said ‘Les Braves’ which shows that the Germans do think something of the British Army’.

It would appear that both graves were later lost as both Lieutenants Hanbury-Tracy and Nugent are commemorated on the Ploegsteert Memorial, along with many other men of the battalion.

Above: The Ploegsteert Memorial (courtesy of Nick Stone / www.invisibleworks.co.uk)

Hugh Taylor was born at Chipchase Castle, Wark on Tyne, Northumberland on 24 December 1880, the only son of Thomas and Moira Taylor. His grandfather, also called Hugh Taylor, was the founder of Ryhope Colliery.

Above: Captain Hugh Taylor

Above: Chipchase Castle

Above: Ryhope Colliery circa 1900

Hugh was educated at Harrow and then Balliol College, Oxford – his widow would later remark that he had said that the happiest time of his life was his four years at Oxford.

On leaving Oxford, Hugh was commissioned in the Scots Guards in 1904. In 1907 he married Mary Stuart, the daughter of H. Villers Stuart MP. Hugh and Mary had one son, Thomas Brian Geoffrey, born in 1909 who died in 1915. In the 1911 Census, Hugh and his family were living in Chelsea, London with a butler and six servants within the household. His daughter, Katherine, was born in March 1912. His widow died in October 1922.

By June 1914, Hugh had become the Unionist candidate for Sunderland, making several visits to the constituency.

On 2 January 1915, the Newcastle Daily Journal carried an eye witness account of Captain Taylor’s death from a wounded Scots Guardsman, Private Power. He recounted that in the initial attack

‘…we had proceeded about 50 yards when the enemy turned on us a deadly and disastrous machine and rifle fire. Many of the Scots Guards fell but the others rushed forward undaunted….it was in this charge that Captain Taylor was wounded. We were nearing the German line when the officer was noticed to fall. Two men went back to fetch him but when they found him, he shouted ‘Go on, leave me. I am all right. Look after yourselves’. The men obeyed……. He was never afterwards seen by any of the men in our battalion. The general impression among the men was that the wound proved fatal, or that he was taken prisoner and died subsequently. ‘He was a brave soldier and a good officer’ added Private Power, ‘and we were all grieved to lose him. He was a real hero’.’

Captain Taylor was mentioned in Sir John French’s dispatches dated 14 January 1915 ‘for gallant and distinguished conduct on this and other occasions’.

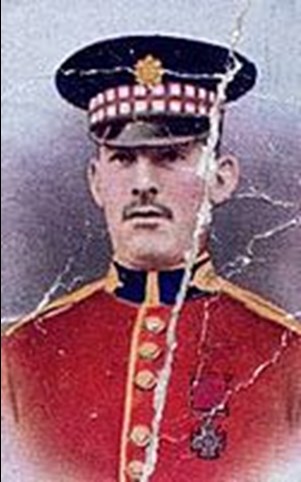

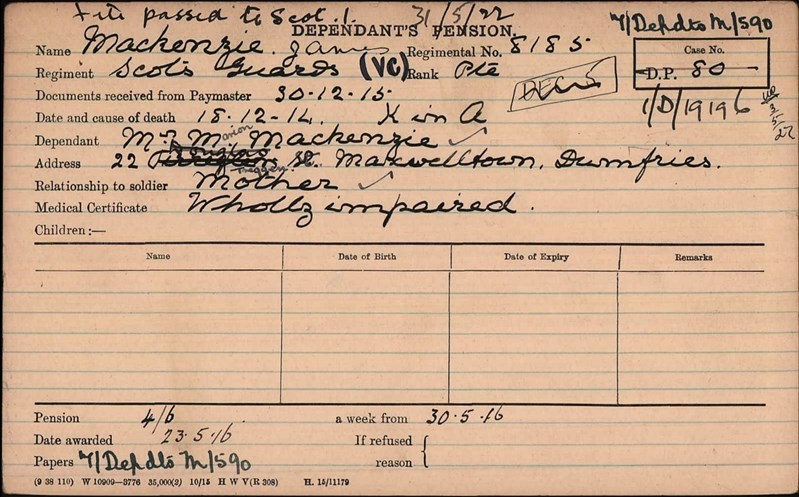

Private James Mackenzie of 2 Scots Guards won the Victoria Cross for his actions at this time, whilst acting as a stretcher bearer.

Above: Private James Mackenzie

Born in Kirkcudbrightshire on 2 April 1889, he enlisted in the Scots Guards in February 1912. The citation reads

‘For conspicuous bravery at Rouge Bancs on the 19th December in rescuing a severely wounded man from in front of the German trenches, under a very heavy fire and after a stretcher bearer party had been compelled to abandon the attempt. Private Mackenzie was subsequently killed on that day whilst in the performance of a similar act of gallant conduct’.

A comrade later wrote

‘He was returning to the trenches along with me and another stretcher bearer when it occurred. We had only two or three cases that morning, so the last one was taken by us three. After we took the wounded soldier to hospital, we returned to see if there were any more. There was a very dangerous place to pass, I went first, followed by another, then James came behind, which caused his death. He was shot in the heart by a sniper, and only lived five minutes’.

James is commemorated on the Ploegsteert Memorial.

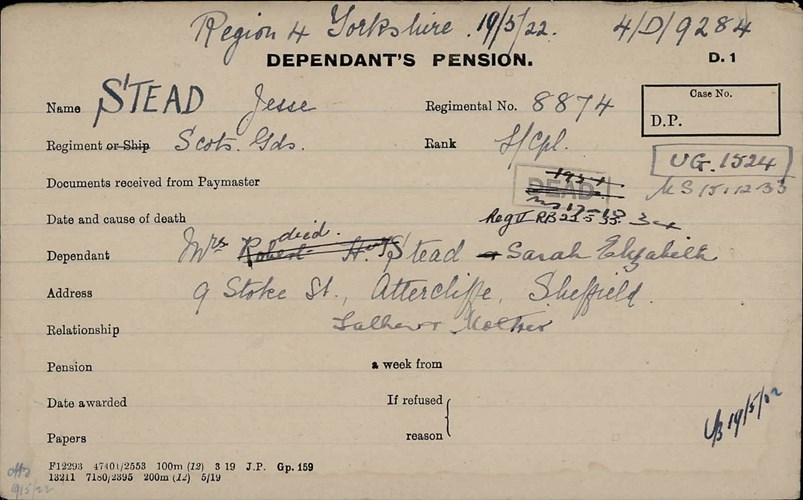

A young Lance Corporal from Leeds, Jesse Stead, was awarded the DCM. The citation, gazetted on 30 June 1915, stated

‘For conspicuous gallantry on 18 December 1914 when he left his trench, under heavy machine gun fire, and dragged two wounded men to safety’.

Jesse was killed that day and is also commemorated on the Ploegsteert Memorial. He had enlisted in the Scots Guards in February 1914, stating that he was 19 years and 45 days old but this overstated his age by one year. He was in fact 18 years old when he was killed.

In a final postscript on the attack, the War Diary quotes the words of the IV Corps Commander

‘The Corps Commander is sorry that the trenches could not be held, and he much regrets the loss of so many gallant officers and men. The attempt though not completely successful in itself has been of great use and service in the general plan of the Allied Armies’.

Article by Jill Stewart, Honorary Secretary, The Western Front Association