14 July 1918 : Flight Lieut. Quentin Roosevelt

- Home

- On This Day

- 14 July 1918 : Flight Lieut. Quentin Roosevelt

Quentin Roosevelt was killed in action on this day in 1918.

Quentin was born on 17 November 1897. His father was Theodore Roosevelt, and his mother was Edith. Quentin was the youngest of six children. He was four years old when his father became US President, so he grew up in the White House from 1901 to 1909.

Above: Half-sister Alice sister Ethel, and brothers Ted, Kermit and Archie.

At age 11 in 1909, he spent the summer with his friend Hamilton Coolidge and his family in France. Quentin was educated at Gorton School and then Harvard from the fall of 1916.

In August 1915, Quentin Roosevelt and two of his brothers attended the camp at Plattsburg, which was set up to train junior officers.

Writing to his fiancée from Harvard in 1917, he expressed his view regarding the war in Europe: "We are a pretty sordid lot, aren't we, to want to sit looking on while England and France fight our battles and pan gold into our pockets?"

Quentin was greatly admired by his colleagues, popular with his fellow World War One fliers, and possessed great ability, flair, and intellectual ability. Sadly, his life was destined to be brash, brave, brilliant, and all too short.

He was no stranger to France, having been sent there for the summer with his friend Ham Coolidge to stay with the Normant family when he was 11. We know this and so much detail over ten years through the detailed and evocative letters he wrote home to friends, family and close acquaintances. We learn of his fascination with all things mechanical, such as after a visit to an air display at Rheims, where he saw an Antoinette flying. At the time, he bought a model aeroplane operated by an elastic band. He was mechanically minded and liked to tinker with motorbikes and automobiles.

In May 1917, Quentin dropped out of Harvard to join the newly formed 1st Reserve Aero Squadron, the first air reserve unit in the USA. For the first three months, he was limited to supply duties and then flight training, and it was only on 9 July 1918 that he became a pilot in the 95th Aero Squadron, part of the 1st Pursuit Group based at St Cloud.

As a transport officer, Quentin was in charge of 52 trucks. Though still only 19 at the time, he was a natural manager and leader, trying out men in different roles until he found where they were most suited, taking the initiative to foresee problems and work all hours to get things done. In due course, with great reluctance from his superiors, Quentin was able to transfer to the newly formed 1st Reverse Aero Squadron at the famous Issoudun training base where his first services were running the flying school.

He worked for the Commanding Officer HQ detachment of 600 cadets and 40 officers, working nights to get a few hours to fly. He remained in this position for months despite his protestations at wanting a combat role as his superiors felt they could not find someone of his calibre to replace him.

‘There’s lots of work to do, but no one else to do it,’ he wrote, adding that there was ‘lots of war to go around for the rest of us’. He rejected spending three months in Paris testing and flying planes out to squadrons as he wanted his six months on the front first. His time training and training others was well spent, testing, pushing and experimenting with his plane and having different kinds of shooting practice - at balloons, using a parachute while a record of your shots was kept - which in Quentin’s case were considered very good. From a French perspective he showed an ‘esprit tres militaire, beaucoup d’allant’. He was so proud of his scorecard that he sent a copy home. When a man became ‘stale’, he’d send him to Paris on six days' leaves, which generally did the trick; he’d have made a great coach.

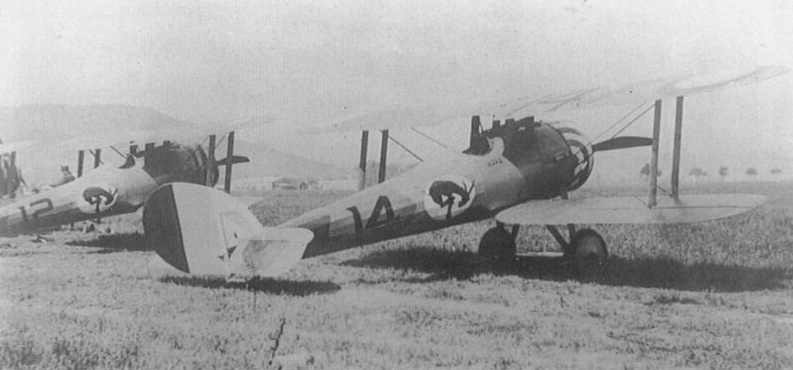

He complained of having no planes, then having planes but no machine guns. At one stage, there were 2,000 US airmen but only 1,000 planes. And then, given the few planes they had, being sent out on decoy work to lure German planes into combat for others to deal with. The ground crew cheekily painted ducks on these decoy planes.

Quentin describes flying a Curtis and then a Nieuport wearing an application named' teddy bear’ against the cold. When the weather was questionable for flying, he would go up to test it out before taking others out on training—he was that kind of person. He wasn’t a stickler for rules. On another occasion, he broke formation at 1000m when he was about the Chateauroux hospital so that he could fly down and show off to the nurses.

He describes flying stunts and formation flying.

When not in the air, he’d go on motorbike trips and had one smash. He claimed to his brother that flying was ‘as safe as an auto’, though, in Quentin’s hands, neither car, plane or automobile could be considered ‘safe’ as he was excited by speed and at 19 had a ‘devil take the hindmost’ attitude.

Quentin was just as reckless with his health. He had a cough for over a month without treatment or rest, which turned into pneumonia—which set his plans back, of course. He’d fly to Paris to visit his sister, drive to the Arcachon coast for a swim, and dine often with both French and American friends and officers.

Proving himself more than competent, he demanded and duly received his pilot’s wings. On 8 June 1918, he sent an excited cablegram to his mother to announce that he and Ham Coolidge were finally moving to Orly with a transfer to the 95th Aero Squadron on 18 June as part of First Pursuit Group, the aerial gladiators of the American Airforce. Quentin famously had his plane painted up like a Liberty Bond ad; he wasn’t happy with the plane though. It had problems and weaknesses, and he knew them. You get the sense that he thought that in the air, he wouldn’t be in fair combat and that they were no match against a Fokker. Two weeks later, he writes that he had spent 6 to 7 hours over enemy lines.

The famous flying ace Eddie Rickenbacker commented his flying style was bordering on suicidal with great contempt for danger. Quentin argued that training in doing ‘stunts’ was essential to knowing how to get out of any situation successfully.

"He was reckless to such a degree that his commanding officers had to caution him repeatedly about the senselessness of his lack of caution. His bravery was so notorious that we all knew he would either achieve some great spectacular success or be killed in the attempt. Even the pilots in his flight would beg him to conserve himself and wait for a fair opportunity for victory. But Quentin would merely laugh away all serious advice."

He claimed his first victory only a day after his squadron was posted to Touquin and the front lines. He wrote to his brother saying that he would be rested after a six-month stint. He hadn’t expected there to be a second, and of course, he intended to survive the ordeal.

When A.I. Sturtevant was killed, Quentin wrote to his brother that there was ‘no better way - if one has to die’ - ‘30 seconds of horror and it was over.

Quentin had plenty of early near misses - on 11 July, he was out with 30 planes or more, on instructions to stay on their side of the line while on patrol when spotted by six ‘Bosche’ their patrol climbed high to avert a fight by Quentin’s plane struggled to keep up and he risked being picked off as the straggler, but ‘you get so excited that you forget everything’ he wrote. On another occasion, while flying, he became separated in the cloud, rejoined his formation and only after a few minutes realised he was flying in formation with three German planes - unnoticed at the rear he picked one off and then managed to escape - his first so-called ‘victory’.

Soon after this, he got into a fight, only to have his gun jam after two shots. Reading this, his brother Kermit must surely have sensed the inevitable was coming. Next, Quentin describes how he ‘caught a wing’, did three summersaults’, and survived a smash (sic) landing.

He describes how Guynemer was remembered and honoured, similarly to Baron von Richthofen.

He was killed on the morning of the 14 July, a day of celebration in France and a day of events at the airport that he had been instrumental in planning.

He had ‘so many friends, from so many different walks of life.’

He had shot down a German aircraft on 10 July 1918 but was then, only four days later, caught up in a massive aerial engagement at the commencement of the Second Battle of the Marne. He was flying a Nieuport 28 when he was shot down above the Chamey behind German lines.

His letters were collected by his brother Kermit, who lovingly and carefully edited into this book which gives a picture of his headstrong, dashing brother poignantly including the many letters of tribute from Quentin’s fellow flyers. Poignantly, he wrote about the place in Paris he would like to visit after the war and the shopping he would do. He also reflected on the view of those in authority in America who grossly underestimated the strength of German resolve.

‘He put his whole heart into everything he did, whether rolling dice or developing pilots for war’.

He describes Paris with its crowds of young men in men in uniform, the war wounded and women with a haunted look on their faces. Writing home, he said later, made him ‘feel gloomy’ when he started looking at war in its entirety - so he tried simply to take things day by day. He described France as ‘the muddiest country I have ever run across. I don’t see why the Frenchmen don’t turn into frogs by natural selection. From his perspective in May 1918, the war in France had another 18 months to run.

‘Men who, perhaps have lost the zest for life

May find it in a boy‘s keen zest for death,

When young life found it sweet to fight and die

If only Liberty in peace might live.'

Eleanor Cochran Reed in The Times, New York

Flight Lieut. Quentin Roosevelt

14 July 1918

Quentin Roosevelt’s three brothers also served in the First World War as officers

Research by Jonathan Vernon.

Sources:

US Headstone and Interment Records

Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quentin_Roosevelt

Illustrated London News, 27 July 1918.

‘Quentin Roosevelt: A Sketch with Letters (1921) Kermit Roosevelt

Airminded.net 'The Nieuport 28'