Ep. 174 – Ypres and its meaning through time – Prof Mark Connelly & Dr Stefan Goebel

- Home

- The Latest WWI Podcast

- Ep. 174 – Ypres and its meaning through time – Prof Mark Connelly & Dr Stefan Goebel

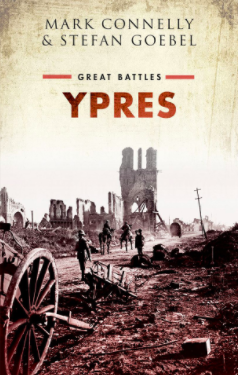

Professor Mark Connelly, Professor of Modern British History, University of Kent and Dr Stefan Goebel, Reader and Director of the Centre for the History of War, Media and Society, University of Kent, talk about their recent book on Ypres. This is published by OUP.

Transcript

Welcome to ‘Mentioned in Dispatches’, the podcast from The Western Front Association with me Dr. Tom Thorpe (TT). The WFA is the UK's largest Great War History Society. We are dedicated to furthering understanding of the Great War and have over 60 branches worldwide. For more information visit our website at WesternFrontAssociation.com.

It is the 7th of September 2020 and we have returned from our summer break.This is episode 174.

On today's podcast I talk to Professor Mark Connelly (MC), Professor of Modern British History at the University of Kent and also his colleague Dr. Stefan Goebel (SG), Reader and Director of the Centre of History of War, Media and Society also at University of Kent, about their recent book on Ypres. This is published by Oxford University Press.

I spoke to Mark and Stefan over the interweb from their homes in Kent.

TT: Hi, Stefan and Mark welcome to the ‘Mentioned in Dispatches’ podcast. Could you start by telling us about yourself and how you each became interested in the Great War.

SG: Well, thank you very much for having us on the program Tom.

We're looking back I'm actually quite surprised I got interested in the First World War as a student at all. We never discussed the First World War at school - merely as a prelude to the Weimar Republic. First of all, it didn't really have a big role in our family memory either and it happened when I started my PhD my parents were somewhat consternated - because they believed that I should focus on a ‘real event’ - such as the Second World War.

It was really only until arriving in the UK as a university student that there I saw the courses on the First World War - and Armistice Day had just been rejuvenated in the 1990s as a ritual, and then I discovered that the First World War was referred to as the ‘Great War’ which I initially thought was the Second World War and then I became interested in the First World War - primarily through its Monumental Legacy - the memorials that started to fascinate me - this combination of artistic expression and private grief - and that's how I got drawn into the study of the First World War.

And so initially the focus was very much on the home front - home front memorials and through this route I've become interested in battlefronts and also the ‘monumental legacy’ that have shaped the battlefront and I assume it's not that different for Mark - from a trajectory from studying war memorials in London to Great War Battlefield Monuments at Ypres.

MC: Yeah. Absolutely. I think you know, for me, I always was interested in history and it was a very traditional boy’s thing - particularly growing up in Britain in the 1970s where the two World Wars were all around us, more particularly the Second World War - but what really, I think, got me going on the First World War was walking regularly passed my local war memorial - just going on shopping expeditions with mum and such - and being amazed at what I later found out were called ‘puttees’. There was this statue - and men actually wore these things tied round their legs did they ? And I'm sort of thinking 'they would normally be wearing that wherever somewhere it was a bit wet?/ They just possessed me. Why on Earth would you have these things? So that was what was always in my mind.

And then when I was 13, one of the things I got for my 13th birthday present, which really did set me on the course, but I think it's probably true for a lot of people - I was given a copy of Martin Middlebrook's ‘First Day of the Somme’ and I read that book and just found it absolutely amazing.

And then in 1986, that anniversary year of someone - just on my O' levels - and as a little treat my parents said why don't you go on one of Martin’s battlefield trips - because we found out that he had these Battlefield tours and I can still remember stepping out at the first cemetery - it was always Dud Corner Cemetery at Loos.

I think just being amazed and then I had this total - bringing together of the tracks of this military history thing and the way the war was commemorated - it suddenly hit me standing there in those cemeteries and led me on the path to to start thinking about commemoration. And then, as Stefan said, really in the earliest days of my serious study was about ‘commemoration on the home front’ - and gradually it's gone back to the battle front.

TT: So when we actually talk about Ypres, what exactly do we mean?

MC: I think we were really interested in the way one particular site just collected so many physical memorials - and the length of its afterlife as well - it wasn't as if it was a place that petered out in terms of significance - and it bounced back after the Second World War and its such an important part of Belgian’s regional economy.

And also the way in which it was a legend which went across the combatant nations - particularly for Britain and Germany. But Belgium and France also had a stake in it. So to find - a battlefield where all of the combatant nations of the Western Front actually felt they had a stake in this place just made it fascinating.

SG: Yes - there's been a tendency in the research and the First World War to emphasize the global - we are now encouraged to think about the First World War as a ‘global war’ - but we wanted to show that Ypres was a global war and a local war. It's the place where people from five continents converged on a very specific place on the map between 1914 and 1918 - where various nations have mapped their memories onto the city and the Salient since. And this turned the city of Ypres and its environs into what we’d call a ‘transnational site’ of experience and memory. And connected to that, is our book doesn't start in 1914, and it doesn't end in 1918. We show that the ‘making of Ypres’ as an international icon started long before the First World War - and that this Battle for Ypres continued well after 1918, in terms of symbolism - of reclaiming the landscape.

As Mark said, tourism played an important role in these commemorative practices of the interwar. And, we often experience the First World War as tourists - our readers will probably recognise themselves in our book. They are part of the story that we tell. How tourists are so very important in making sense of this space and commemorative site ever since 1918 - in fact tourism started a bit earlier, didn't it Mark?

MC: Yeah indeed.

TT: Yes, you'll begin to talk about your book on Ypres today, which is described as a ‘transnational interpretation of the meaning of Ypres’. Could you tell us about what your book is about and why you both decided to write it.

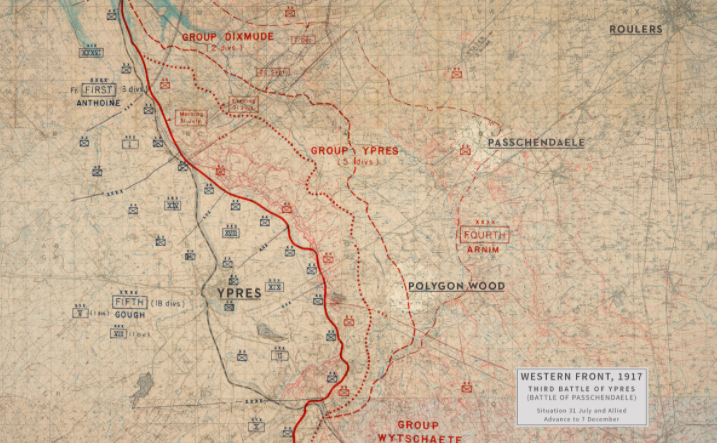

MC: That was one of our first fun intellectual and emotional games about this - realising that it's such a flexible geographical term, which is often driven by a national standpoint. We realised right away that there is a slightly different thing, as far as the British Empire is concerned, between ‘Ypres’ and the ‘Ypres Salient’ - they are ever so slightly different - Ypres as a region ... is the bit that stretches from about Boezinge there in the north down to the French border down to Ploegsteert, whereas the Salient is ... Hooge and then hinging back again.

For the French and the Belgians it's somewhere that also includes these are the Yser front - it runs as far as Dixmude and for the Germans there is that incredibly redolent phrase of Flandern … everything that is Flanders, this was slightly broader precision in the kind of focal point within a larger landscape of Flanders.

SG: Especially the elasticity of the geographical place names has contributed to the fascination of the place, but also a lot of confusion - so similar to the British distinction between Ypres and the Salient - in the German case, you have Langemark and you have ‘Flandern’. Now Langemark of course Village just outside Ypres but in the discourse of wartime and post-war, it could also mean the entire Ypres salient and the entire Ypres battlefield and more. Although it could also mean the entire Western Front - Langemark wasn't just a place but it was also an idea. Now ‘Flanders’ or ‘Flandern’ tended to refer to the whole sector from the Franco-Belgian border to the sea, but often applying a running line from the salient itself northwards to the sea. So the German understanding of 'Flandern' is slightly different from the British notion of Flanders and Ypres but then in some contexts are learning referred more specifically to the battles of 1917. So there's a lot of confusion. And this is part of the story - the elasticity of these place names that we try to chart in our book, that they can refer to particular battles, to particular dates, to particular places ... but sometimes they can also describe an entire region that is very vaguely defined by geographical features.

TT: So could you tell me about what Ypres was like before the Great War?

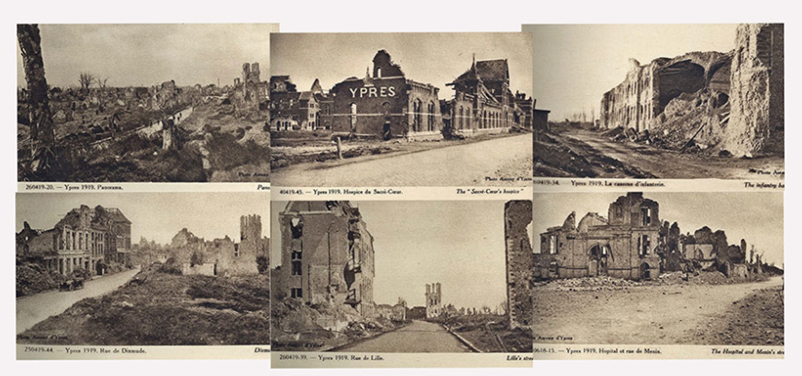

MC: Yeah, Stephen was saying earlier. I think what's really important about the way it's going to come to be perceived in wartime propaganda of all of the combatants and then the effect that will have on the post-war remembrance of the place - is that it is drawing upon this deeper knowledge. It's clear from the development of the ‘Western European industrialised world holiday pattern’ - that's starting to emerge from the 1860s, 1870s - that with railways, with steamship travel for the British across the the Channel, and the growth of the tourist guidebook - Ypres, very quickly starts to appear as a distinct Flemish City - with a distinctive history, which ties in, certainly in the English language - tied in to a history of Britain, but more particularly of the East Anglia through things like the wool trade and everything else. There was this great, genuinely Anglo-Saxon sense that there is a shared Gothic culture to be celebrated here. So to see in both British and German, English and German language guidebooks, a celebration of a great historical site full of these amazing buildings - and in particular, you know and they were always keen to stress ‘Europe's largest secular Gothic building’ in the Cloth Hall sits here - here is somewhere where you as the ‘educated tourist’ really should take in and should think of it in ways similar to the way you consider Bruges.

So it starts to become this tourist site, but what's really quite uncanny is because there is this knowledge of how vibrant Ypres had been in the medieval economy by the late 19th century its already being spoken about as this kind of ‘spectral ghost town’ - that it's a shadow of what it once was. So, as with so much of the First World War, you know part of the cultural fascination is that there is ... an unwitting foretelling of what's going to happen here - because it is remarkable how often it is referred to as a ‘City of Ghosts’. There is one description that says the Cloth Hall could ‘swallow an army of men’ - and it's a spooky reading that was written in 1904 or 1905, whatever it is. So it is this place with a distinctive profile. And of course as any Londoner interested in their architecture would have known, the great Gilbert Scott was interested in the Cloth Hall which explains, in particular, the roof of some St. Pancras Hotel - it's there - The Midland Hotel. So yeah, it's this place that's intertwined in European culture, certainly Western European culture. So Stefan do you want to add anything you want to add a particular up the German perspective on it?

SG: Well, I think what is interesting is that they're they're converge - the perspectives - this idea of City of Ypres as a ‘City of the Dead’ is also present - in German discourses before 1914 - an uncanny element of unwitting foretelling is also present in German tourist guide books. Perhaps they didn't quite have the same obsession with Ypres and its medieval past, maybe because Ypres was a gateway for the British to the European Middle Ages and European medievalism - and German visitors didn't perhaps need the same kind of visual stimulus to think about European Middle Ages.

Also - it was much easier to access for British tourists. I mean, there are other places to visit for German visitors before the First World War. So gathered again to turn to - were probably more prominent on the tourist Trail. But it's certainly there as a symbol in particular as a symbol of decline - of this proverb that ‘Ypres was the city of the dead’ - is already widely before the First World War too.

TT: We come onto the conflict. So what happens at Ypres during the Great War? I know it's a massive subject. We don't have a great deal of time. But in 30 seconds …

MC: In many ways. I think the fascinating thing about Ypres militarily is exactly the same point that we were making about tourism - and why it's going to become a place of great post-war commemoration. - it's the accident of geography, isn't it?

There is this city that sits at the confluence of lots of ancient and modern communication links - and it’s the gateway to the coast - to the to the channel coast. So for both France and Britain and for Germany, there is this recognition that if you can dominate Ypres, if you can capture it, you effectively open the gateway to the coast.

So in the Great War, as we know, defensively in 1914 Britain and France, have to hold on to it - as they do then again in 1915. In 1917, what they want to do is chuck the German forces a long way back from it because, as well as protecting their own hinterland, what it will do, will be to unravel the Belgian Coast which will be brilliant in terms of defeating the submarine threat - and opening up - logistics for the Allies. So that accident of geography is what makes Ypres so important militarily - and it's intimately connected. It strikes me, me to its pre-war census as a tourist destination - and its post-war position as a battlefield tourist destination.

SG: It might be worth just zooming in on one moment In in the war. That is 11th of November 1914 - the German Army issued a communiqué that later on every German knew almost by heart. German youngsters would have to memorise - that communique said, let me just quote from it

‘West of Langemark Young Regiments broke forward singing Deutschland, Deutschland Uber Alles against the first line of the enemy's position and took them’.

Now almost every word in this statement is wrong : ‘West of Langemark’ is very vague - the fighting actually referring here to place called [Boegshorte], but that doesn't role of the German tongue in the same way as Langemark. ‘Young regiments’ implied that these regiments were composed of young people - students, which wasn't true. ‘Singing Deutschland, Deutschland Uber Alles’ - wasn't true either. There was some singing, perhaps sometimes, in order to avoid friendly fire, but there is no evidence to suggest that they storm forward singing the German Anthem - and they didn’t take the enemy's position either.

So there's this one the sentence of 15 words and almost nothing is correct - but it became the stuff of myth. The whole the Ypres Western Front story was - telescoped into this one moment in November 1914.

TT: So what did Ypres become for the combatants who fought over it during the Great War?

MC: Well, I think for the for the British and the British Empire, yo, it's back to that 11th of November 1914 moment which comes so rapidly after the 31st of October 1914 - and it's going to encapsulate the whole symbolic significance of it - that Ypres is a place of immense sacrifice - and it's a sacrifice that is made in order to keep the enemy from Britain's doorstep - and I think that's going to be the crucial association with Ypres - if Ypres falls the ‘Heart of the Empire’ is in danger.

So it takes on this immense symbolic sense of being the ‘shield of Britain’, which is held up by Britain's contemptibly little Army in 1914 - and then the others that come in its wake take up that mantle and step up to it. And that also then allows that idea of it becoming a place of sacrifice - allows it to be embedded in wartime propaganda, as somewhere where British Imperial soldiers carry out a quasi-Holy Duty.

And again, the sheer geography of Ypres lends itself. The fact that there is a main road running out of it, you know towards the enemy lines means that can be compared the Menin Road can be compared with a Via Dolorosa - and it's often referred to as the British Empire's Via Dolorosa, and as John Buchan will say, and then becomes common in British discourse, and Imperial discourse - ‘what Verdun is to France, Ypres is to Britain.’ So it becomes this immensely important site of ‘bloody defiance’ against an extremely brutal and nasty enemy - proven, of course in 1915 by the use of gas - and it's never really going to shake off that mantel at all. And for the Germans, Stefan - what's your is it really encapsulating that ‘14 moment?

SG: Yes, in particular Langemark stands for the moment when the German expectations were crashed - and where the war movement came to a halt - and it wasn't so much ‘military defeat’ - as being defeated by the elements - with the opening of the sluices and the flooding of the landscape - the myth emerged that they were ‘undefeated in in the field’ but tricked by the Belgians who had, in a very 'unsporting' fashion, flooded the landscape and thus brought the German advance to a halt. And that narrative is repeated in the Cemetery at Langemark that's got this very peculiar design with a moat surrounding it - which is supposed to be a symbol of the flooded landscape of 1914. So Langemark marked the point where we see this ‘war enthusiasm’ of 1914 extended into the autumn - the singing of the anthem during the advance, but also the moment where the high expectations of the military victory had to be buried.

TT: So how do people regard the city after the Great War and what was their relationship with it?

MC: Well, I think the British, certainly the British Empire - it's the claim on the whole place for for the British Empire that this is peculiarly ‘our spot’ that the the rhetoric which therefore immediately begins to marginalise the French, who of course played an enormous role, particularly in the First Battle of Ypres - but that is already kind of being airbrushed from an anglophone vision of the Salient. This is the very important French contribution to the Third Battle (of Ypres) is being rather swept under the carpet. And the fact that the French do rather well in the Third Battle, he's obviously not something that the British in talking about so - and of course the British have the the huge advantage of having the boots on the ground in Ypres. I mean literally having the Army there to 1921 and that's gradually morphing into the Imperial War Graves Commission, which gives the ritual the springboard and the British Empire to sink its claws in to the landscape - and the fact that the local authorities are relatively compliant or friendly about British intentions, means that it can begin to ‘colonize’ and own this place.

One of the great - semantic legacies is that because so many of those local people who’d either remained or came back, they start to use the old Tommy names for the place as well. They become as conversant in them, you know as the soldiers of the British Armies - that that retains a kind of semantic hold over it - You know, that no one knows where her Harringuard Forest or Wood is, but they know where ‘Stirling Castle’ are, you know or’ Dumbarton Woods’ or ‘Hellfire Corner’. So these places get stamped into it. And it's kind of left to the other combatants to scrap around the edges to see what the British haven't claimed by the end of it.

SG: I think that was also want to notice the the registering of ‘holy grounds’, Ypres is refer to us the ‘holy ground’ of British arms. There are some commentators who suggest that ‘Jerusalem is to the Jews’ as ‘Ypres is to the British’ . And this is not just a rhetorical exaggeration.

Reflects the status the city and the Salient heart in the British imagination in the interwar period and we can duly recognised by the Belgians - and they conferred on the small British colony that had emerged there, the title of the official title of ‘British Settlement’. I think that was in 1931. So Ypres became a kind of quasi-colonial outpost - accepted by the Belgians. Now the critical difference was that the British had very good access to Ypres. For German visitors it was much more difficult to travel to Ypres because of passport restrictions and the financial situation - and it's only from around 1928 onwards that we see this changing. In 1928 (again) starts to build a significant War Graves Cemetery at Langemark, which becomes a focal point for nationalist sentiment in the late Weimar Republic. Until then, until about the late 1920s, the German War Graves had to be looked after the Belgians that was stipulated in the Versailles Treaty and it was a campaign to use of all grades the more grace issue to campaign against the Versailles Treaty, on the one hand, but also to undermine the legitimacy of the Weimar Republic. The Weimar Republic couldn't do very much about war graves until the mid to late 1920s, but nationalist firebrands used the dilapidated state or German war graves in the early to mid 1920s as a propaganda tool against the Weimar Republic to show that they were not caring about the war dead from the First World War.

So when the Langemark Cemetery is built between 1928 and 1932, this becomes a focal point or the imagination of a new type of national community - and it seems to be encapsulated in the design of the Langemark Cemetery which doesn't give the dead individual graves, but instead puts the emphasis on the ‘community of the dead’ - not on the individual sacrifice, but on the sacrifice on behalf of the nation - commemorated here as a group of soldiers, as a ‘band of brothers’. So ironically the individual German dead had a greater chance of being commemorated. It as an individual if he was buried in an appear Imperial War Graves cemetery than in a German cemetery.

TT: Now, how is each scene today? And how has it been over the centenary by various nations?

SG: I think in order to understand the centenary today, we've got to return to the 1970s. That's the point when Germans started to stay away from Ypres. Since the 1970s Germans have not felt the same emotional connection to the war dead and in particular to the landscape or Western Flanders, but previous generations had and with the passing away of the veterans generation during the 1970s - the presence of German visitors in and around Ypres declined dramatically. Ironically, precisely at the moment when British battlefield tourism was slowly starting to pick up again. So the consequence of this is that while Langemark has still has a resonance as an idea, and a sort of a political ideology - something that is problematic - Ypres as a place, hasn't really attracted large numbers of German visitors. So there's a disconnect here between the war, and the landscape of war. Now the centenary has changed this a little bit. There's been a great influx of German tourists, but fundamentally this deep emotional connection between landscape and the memory of the First World War is something that would be very difficult to re-establish in the German case - and I suspect that now we're coming into the ‘20s that this influx of German visitors will decline again. I can't see this as a long-term Change in the commemorative trajectory since the 1970s. But I think there's also a British story of decline after 1945, isn't there Mark?

MC: Yes.

SG: Ypres is no longer the [unrivalled sidewalk operation at the most of the night in the it's gay].

MC: I think the fascinating thing about ... the gradual ‘decline and fall’ and then resurrection of Ypres - I mean by gradually after 1945 when as you might well expect - the tensions of British people are elsewhere - and it creates a whole new set of sites where the bereaved want to visit and also for battlefield tourism. I think what's interesting is the way Ypres has managed to re-emerge and - hold its end up against the massive rise of the ‘son of the Somme’ - from the 1960s. Throughout the 20s and 30s Ypres is undoubtedly, you know the central focus - and which is quite interesting given you'll see that the huge ‘blood commitment’ that Britain makes through its new armies which suffer so badly on the Somme. Yet Ypres always out punches that I think that's partly because Ypres is an Imperial battlefield - and par excellence Britain is an imperial power in the 20s and 30s but by the 1960s as we know all of that has kind of gone that the the last knockings of Empire around but Britain is this great power is well on the slide which arguably makes the Somme and particularly, of course as we know the Somme for many British people actually means the First of July 1962, not much other than that. It makes the the kind it the Somme a ‘Kleiner Englander’ view of the world - because it's all British units ... apart from some Newfoundlanders - and a bit of Indian Cavalry behind the lines - and of course the crucial thing, which is becoming more important from the 1960s, of Ireland - Northern Ireland. So it I think the Somme starts to create its own iconography from the '60s, which is then encouraged in visitor terms by the sheer practical things like the growth of the ‘roll-on roll-off ferry’ and the French finally getting around to a motorway network - so you can actually visit these places, which gave it a real resonance - through the Centenary Ypres has reasserted itself because it can become a synonym for the whole War - largely because of that practicality. If you haven't got a lot of time and want to see a battlefield you can do it in a day trip. You can get there a coach tour operators can take you there and bring you home in a day. You've got a major memorial that sits in the middle of a city where there is a powerful daily ceremony - and within seconds of it either you finishing you can have chips and beer - you can't do that on the Somme can you? You can visit the architectural masterpiece of the Commission that's the Theipval Memorial, but you're trapped there. If you visit it. There's nothing for you to do immediately afterwards. So Ypres has all these kind of practical things which I think through the Centenary has helped to reassert itself because of its long tourist infrastructure - it's able to swallow numbers.

But I think what's very interesting during the course of the Centenary, and this is where I'm going to become a bit Ben Elton, you know, "bring in a little bit of politics", is the fascinating thing that happens on the British, of course Brexit happening through the course of the Centenary - and what that means your how much people are thinking through what kind of connotation to they impose upon Ypres when they're standing there at the Last Post, you know, are they thinking wow, this was us showing the continentals what for, right? We showed them in two world wars, didn't we - and aren't they? So keeping in the subtleties that that Last Post is being played by local people as an act of homage - who see Britain is embedded in their culture embedded in their lives. And also, of course Ypres, I think these days, because of that is kind of- its War Graves Commission dominance, still means that we tend to forget, and perhaps have forgotten too much during the course of the same Centenary, that Britain fought the War as part of an alliance - that there were others that were alongside it, particularly the French. It's very, very interesting to see you know, the numbers of visitors of the Commonwealth War Graves cemeteries, but still the depleted numbers, you know that go to things like Saint Charles de Potyze this is incredible French Cemetery, which didn't really find itself resurrected as a result of the Centenary.

SG: There's also been an attempt to turn Ypres into a European symbol of suffering during the Centenary. I’m thinking of the summit of European leaders, and them visiting the ‘In Flanders Field’ Museum and being shown around Ypres. So yes, Ypres could be turned into a symbol of Brexit and vision of Britain separated from from the continent - but it can also be turned into the opposite symbol - and that's something really the ‘In Flanders Field' Museum is working on - and stressing the transnational character of Ypres - as a place for Europeans to come together - reflect on the past and build a better future.

So that's the kind of project that Ypres as a ‘City of Peace’ has set for itself - not just during the centenary, this goes back to the post Second World War period where they started to think of Ypres as a place of peace and reconciliation - first starting with veterans others, researchers, ordinary people trying to bring them together to think about peace rather than war - and there the city has a very dedicated piece program as well.

What has been interesting during the Centenary is the much bigger number of former dominion visitors coming to Ypres. So Canadians, Australians, New Zealanders - and what is interesting there if the British can at times show a degree of chauvinism - forgetting the bigger picture - what you could argue is what's emerged over the last ten or so years, and has been really solidified by the Centenary, is a sense in which perhaps people from Canada and Australia think they can explore this landscape without thinking of themselves as people that were doing it under a ‘Britannic umbrella’, you know, their forefathers were very definitely living in a Britannic World - a ‘greater Britain’ - and that's the way they conceived of themselves. So it's been fascinating in the Centenary to watch the kind of splinters jump out here and then to impose even more strongly their own narratives on it - and not look at the broader history of the place.

SG: You can see how they are trying to claim particular spots within the Salient - I’m just thinking about the new visitor centre at (Blacksberg). So the kind of micro geographies that governed commemorations and in the 1920s seem to make a reappearance with particular parts of former Empire now identifying with particular spots within the Salient - this coming back during the Centenary years. Doesn't it Mark?

MC: Absolutely, really yeah.

TT: How has this relationship between us the Belgians and others over what eat me to each and every one of us. How's that actually worked out and does it cause conflicts at all?

MC: It's a fascinating thing isn’t it, that goes right the way back to the earliest days of visiting - this fake distinction between the pilgrim and the tourist - which is entirely fake because as we all know we leap between the two persona ourselves don't we? The most dedicated of First World War students that knows every inch of the battleground, who might think of themselves as exceptionally different to the Day Tripper - at some point is going to buy a packet of chips, or by an unfeasibly large bar of chocolate in Ypres for their friends or all drink Belgium’s liquid heritage.

So we're always jumping between the persona of the pilgrim, or the serious student of history - and that of the tourist. we dip our hands in our pockets, we indulge in the tourist infrastructure - and I think for the flip side that's the way it is for the local community - on one and the same time, they are the people who make a lot of money out of it is absolutely vital to the local economy. And they do a lot of shrewd infrastructure work to make sure that tourist footfall will continue.

And the farming community are remarkably tolerant of Great British tour buses blocking up country lanes when you might want to get a big piece of agricultural kit down it - but by the same token, those people are immensely invested in the spiritual and symbolic significance of the place - as is shown every night in that Last Post ceremony.

You might say, well, not every member of the city comes out every night to celebrate it but I would argue that the sheer fact that they at their very least tolerate it - and allow a massive disruption of their daily lives, and the way that they can drive their cars in and out of their own City, you know - or get through it - every single day of the year - shows that there is this kind of symbiotic relationship between the legacy of the Great War, commemorating it - that there is a short of remarkably tolerant and well balanced set of relationships that that has emerged over the decades.

SG: There's no doubt that tourism and commemorations are also a vital part of the local industry in Ypres. The whole town relies on this income stream from visitors.

There's the occasional danger of trivialisation. We saw this a couple of years ago. When a local butcher came up with the idea of launching a new type of pâté, which he wanted to call the ‘In Flanders Fields’ pâté and there was a Passchendeale pâté and more recently there were see the ‘Ypreats’ restaurant - but that sounds a bit like 'Ypreit' which is a French word for from poison gas coined in the First World War. So sometimes these there can be some sort of tasteless outbursts of this commercial activity but there's always the corrective coming from within the Belgian community and this case the ‘In Flanders Fields’ Museum - but trying to explain to the butcher or the restaurant what they can or they can't do or what they shouldn't. So what whilst there has been tensions over the over the decades between tourists and pilgrims and locals i think overall it's symbiotic relationship.

They rely on each other and this is, as Mark said - the the Last Post was after all a local initiative initiative - a local initiative to commemorate the British dead - and the fact that they resumed this ritual as soon as the Germans had left the city again in the Second World War tells you that this is a genuine ritual. This isn't just put on for tourists and visitors, but there was a deep-felt need, on part of the local population, to commemorate the sacrifice of the British - and their allies.

TT: And I suppose a slightly speculative question for my penultimate one is - what does what will Ypres mean in the future once we're past the centenary and maybe focus has moved to the Second World War?

MC: That's an interesting. I think a crucial thing will be - in terms of maintaining some kind of idea of what Ypres is - that is a practical one of - will the British national curriculum maintain the First World War as a core part of its [teaching] ? - and therefore, will it be still bringing groups of young British people into the city - and then the impression it will create - and the legacy that it creates on them.

So as that one is extremely important. I think there's also a sense perhaps of the way the wider political cultural drift of somewhere like Britain goes - if we're still going to encourage an idea that Britain was at its best in two world wars, and make that a keystone of our culture, I can't see why Ypres should decline too much as a place that people visit. But perhaps with Brexit the idea of British ‘exceptionalism’ and the wider context will continue to be forgotten - and the interesting thing though, the very interesting thing might well be, particularly if international travel does come back to pre-coronavirus levels, is will people like the Australians and Canadians be increasing in their numbers of visiting - and increasing their ‘alternative narratives’ on the place. Will we see that as the big kind of growth area ?

And also, of course the other player that might well become more involved - If we go to anything like the pre-coronavirus drift of the world - is the new player on the Ypres-block in some ways in the Centenary was China - and the association of the Chinese Labour Corps with the city and the way the Chinese government was trying to piggyback on the the back of the history of the Chinese Labour Corps to say something about China as a world power, at the heart of world events, and on the ground in Europe. So they are I think of some of them that sort of interesting trajectories that might go on into the future.

Also the agenda of the ‘In Flanders Fields’ Museum, which is - the most important local player here because their agenda is very transnational - international. Very prominent in foregrounding the Chinese presence through their exhibition works and catalogs. So perhaps the other global developments match very neatly with the intentions of the ‘In Flanders Fields' Museum to stress that this is a local place, but it's also a genuinely international global place - where the First World War as a global war can be commemorated - and researched.

A second prediction for the future would be that this ‘synthesis’ of popular history and academic history can continue - as practiced by the ‘In Flanders Fields' Museum. They have an exhibition that is very popular, very appealing, but at the same time deeply researched - and this coming together of academic researchers, battlefield tourists and others - that is encouraged by the museum through the exhibitions and conferences - maybe that's something that can continue in the future - and and help us to overcome this division between academic and popular history.

MC: Yes, and what I should have added, just to sort of skip back, as he is during the centenary, we had the very first was the first signs of a little bit more show was over in a songs in interesting the Great War in in South Asia, but particularly in India. And if the Indian economy and India's global role continues on the trajectory that it was on - it will be fascinating within the next ten to 20 years to see will there be more Indian visitors who can easily do that axis between again, due to the accident of geography between Neuve Chapelle and Ypres where there is a relatively new Indian Memorial, you know, what might an Indian narrative about Ypres be?

TT: And finally gentlemen, where can people learn more about your book and your research?

MC: The book is available from all good outlets, Amazon and everything else. So very easy to get hold of - and remarkably we’d like to think, you know, I'm sure a lot of the listeners will know things that are produced by University presses can sometimes require you to sell a kidney and your first born and then you can afford about two chapters worth of it. We're very pleased that it was priced reasonably - £20 or so, that that's that's great.

And as for my work, you know, I'm involved, as I'm sure a lot of The Western Front Associations members know, with the Gateways Centre and we've got our website - and my University webpage has got a lot of information and if anyone's got any queries - any questions really happy to have a chat, you know - do look me up via the University of Kent - and drop me a line as a factor.

SG: The book is £15 as a hard copy - a real bargain and you can also read quite a substantial chunk of it online on via Amazon for free. Maybe we can also mention our blog ‘Munitions of the Mind’ - to learn more about the research we do the University of Kent - and our PhD students in particular. So check out ‘Munitions of our mind’ as well.

MC: And Stefan and I also help to co-host and convene a seminar at the Institute of Historical Research at Senate House in London on 'society and culture'. We normally meet once a month on a Wednesday. Obviously. There's a hiatus at the moment, but those are open to anybody to come along. So, please do look at the website of the School of Advanced Studies at the University of London - so if anybody sees any titles there, you know of any papers given and would like to come along we'd be delighted to see them.

TT: Thank you very much for your time.

MC / SG : Thank you so much. Thanks Tom.