One Man’s War : with the Chinese Labour Corps France 1918 by Norman Mellor

- Home

- World War I Articles

- One Man’s War : with the Chinese Labour Corps France 1918 by Norman Mellor

[This article first appeared in Stand To! No. 29 Summer 1990. Members receive three copies of Stand To! each year and have access to the entire digital archive of al l118 editions via their member login].

It was in March 1918 that I was posted to the 4th Bedfordshire Regiment, 190th Brigade, 63rd (Royal Naval) Division, on my 19th birthday. I was just in time to go into action on the Albert-Bapaume road after the German breakthrough. I remained with my battalion until Armistice Day, 11 November 1918, and, being too young for early demobilisation, volunteered to join the instead of having to serve in the Army of Occupation of the Rhine.

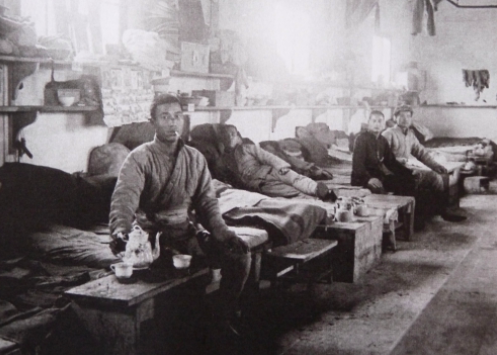

The Headquarters of the Chinese Labour Corps were at Noyelles-Sur-Mer, near Abbeville. The staff consisted of a Captain, a Lieutenant and several other ranks. I was put in charge of the Chinese payroll of about 500 coolies including 1st, 2nd and 3rd class gangers, and one interpreter. This was about the normal strength of a company. The men's pay varied according to rank and ranged from one franc up to five for the interpreter, paid monthly.

Opposite us was the compound of the 186th Company (Prison). It was similar to the British 'bullring' at Etaples and each morning the inmates were drilled wearing the Chinese heavy pack—'about turn!' 'about turn!'—until they were dizzy. After punishment the coolies were sent back to their own companies in the field.

The Chinese, all volunteers and mostly from the province of Shantung, provided labour behind the lines in France, thereby releasing our own soldiers for combat duties. Altogether 97,934 were recruited by the British and at the end of the war there were no fewer than 195 companies working in the areas of the five armies or on the Lines of Communication.

I was with the HQ staff until early 1920, so had plenty of opportunity to get to know these cheerful, hard working and disciplined men. Their parade ground drill was certainly a credit to their military training and the salvage work, unloading of stores and other work they performed was of great value to the British cause. In his book about the Chinese Labour Corps, Sidney Allinson quotes the work done by the 51st Company on the tanks before the Battle of Cambrai in November 1917 when 1000 coolies, working twenty hours a day, fitted 350 fascines in three weeks. This confirms my opinion of the hard working Chinese.

On 20 February 1920, Captain A. R. Jones, Lieutenant Sheepshanks, Sergeant Major F. Webb and I volunteered for repatriation duties. Reporting to the Base Dept at Le Havre, we took control of 1000 coolies and boarded the SS Melita. The Atlantic crossing to St John's, Newfoundland, took five days.

Gathering our human cargo, we joined the Canadian Pacific Railway and steamed off on our seven days journey across Canada, passing through North Bay, Smith Falls, Winnipeg, Portage la Prairie, Moose Jaw, Medicine Hat and so on, to Calgary where we had a stop for a couple of hours. Then on through the Rockies passing Banff and Kicking Horse Pass. Like us, our Chinese friends enjoyed the wonderful scenery. We arrived in Vancouver City without mishap and next day crossed by ferry to the Canadian quarantine station at William Head on Vancouver Island. (I understand that the compound at William Head is now a Canadian Government penitentiary but that there are still several graves of the Chinese who failed to make it back to their homeland.) Here we joined up with another 5,000 Chinese coolies who were awaiting repatriation.

During our short stay here, several arguments and outbreaks of fighting took place in the Chinese compound. Upon investigation it was found that they were the results of old grievances between gangers and the men. After the usual period of quarantine, two officers, ten British other ranks and 4,730 Chinese coolies boarded the MS Dollar. It was named after the Dollar Steamship Company which was founded by a Scot who came from Dollar in Scotland. The ship was built in 1917 and based in San Francisco. The line was swallowed up some time ago by the American President Lines.

The first meal on board was rather chaotic as the Chinese cooks had not boiled sufficient rice to satisfy the whole company. Next day, however, the rough Pacific Ocean came to the rescue as most of our Chinese friends went down with mal de mer. Our destination was Tsingtao in the province of Shantung, China. This port had belonged to Germany and had been captured by the Japanese who were our allies in the 1914-18 war.

After twenty-one days afloat seeing neither land nor ship, great excitement erupted among the coolies when they first saw their homeland again. To see the sparkle in their eyes was a joy to their escorts. When these boys had enlisted three years before, they were totally ignorant of the outside world and had never seen the sea or a ship before. They had now come home, wiser and richer. Most could speak a little pidjin English and a smattering of French too, and were very proud of having served in France with the British Army.

We handed them over to the Japanese authorities, sadly short of two who had died and been buried at sea. The remainder would soon be demobilised and return to their farms or paddy fields in the vast interior of China

We, the escort, stayed on board the Dollar for two more days while she was loading bulk cargo. Going ashore, we experienced our first rickshaw ride round the city to our great amusement. Dead on time we sailed into the Yellow Sea, destination Shanghai. This international city was well worth looking over and we spent seven days enjoying the sights and the different ways of life in this Eastern city.

Our two officers remained in Shanghai and took up business appointments there. The rest of us stayed on board and steamed down the Yangtze-Kiang River to the open sea and south towards Hong Kong. What a wonderful natural harbour it is. Disembarking, we stayed in the Royal Artillery barracks near Happy Valley. It was a complete holiday for us and we were there for practically two months. I got friendly with an Inspector of the Hong Kong Police and he took me round most of the high and low dives there: over to the mainland at Kowloon, up the Peak and to a race meeting at Happy Valley racecourse. He asked me to get 'demobbed' there and join the police. I didn't and we all returned to Blighty via the Suez Canal and were demobilised at Park Royal, London. It was as well that I did for otherwise I doubt whether I would have survived the events of 1941-42 to tell this story.

As a sequel to this, in September 1975, at the age of 75, I made a return journey to France by hovercraft, bus, train, taxi, ambulance (there being no other transport available) and shanks pony. I went to Calais, Lille, Mons, Valenciennes, Cambrai, Bapaume, Albert, Amiens and Abbeville, paying homage to my comrades at several of the Somme cemeteries. And finally on to the site of the Chinese Headquarters at Noyelles-Sur-Mer. The only reminder was the cemetery, beautifully kept, containing the graves of over 400 Chinese who had died as the result of accident or disease while serving with the British Expeditionary Force. This was one of several Chinese cemeteries in France.

I signed the Book of Remembrance and noted that it had been signed the previous day by visitors from China. They too had remembered after fifty-eight years.