Ep.251 – Debating America’s response to the Great War – Dr Neil Lanctot

- Home

- The Latest WWI Podcast

- Ep.251 – Debating America’s response to the Great War – Dr Neil Lanctot

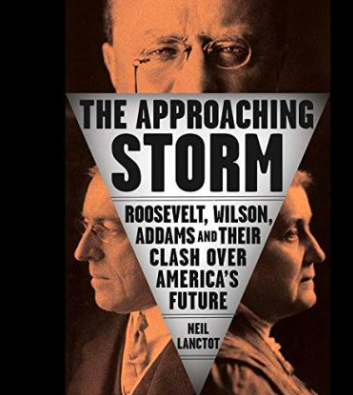

Historian Dr Neil Lanctot talks about his recent book The Approaching Storm which explores the domestic debates and discussions that informed America’s response to the outbreak of the Great War and its eventual declaration of war in April 1917.

The Approaching Storm explores the perspectives of three prominent US newsmakers: President Woodrow Wilson, former President Theodore Roosevelt and social activist Jane Addams and examines how their views on how America should respond to the outbreak of the Great War in Europe mirrored the wider debate in America at the time.

Neil Lanctot, (pronounced “Lank-toe”) is a writer and historian who has written four books. You can find him at > https://neillanctot.com. The Approaching Storm is published by Penguin/Random House.

TRANSCRIPT

Dr Tom Thorpe On today's Dispatches podcast, I talk to author and historian Dr. Neil Lanto about his recent book, The Approaching Storm, that explores the domestic debate and discussions that informed America's response to the outbreak of war in Europe in 1914 and America's eventual declaration of war in April 1917. This book is published by Penguin Random House. Neil spoke to me from his office in the United States. Neil, welcome to the Dispatches podcast. Could you start by telling us about yourself and how you became interested in the Great War?

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:01:16] Well, I'm a historian. I have professionally trained as a historian, have a Ph.D. and ... my initial work in history had been on baseball, which I know is not that big in the UK, of course. But I had done work on the segregated baseball leagues in America, which are called the Negro Leagues, and those had been the focus of the first three books I had written. And after my last book, I decided that I really had done enough on baseball and sports and really thought, I want to find another topic and reach a broader audience ... reach the broader history reading audience. And I started looking at this series of books called 'Our Times', which were written by an American journalist in the early 1930s, late 1920s. He had written a series of six books on the past 25 years of the American century. They were very fascinating books even to read now, almost 100 years later, because they're written from the perspective of someone who lived through the times and knew everyone really well and knew all the movers and shakers. But when I got to his book on World War One in America, I really realised this is very interesting stuff. America's involvement in the war and how we got into the war, and I felt there had not been much written about that - and that really was my jumping off point to doing this book. I felt it was a story that was really not being told that well, or that often - at least in the United States literature. And I also came to believe that the American decision to go to war in 1917 was really one of the most important decisions in the 20th century, because I think it did have a great impact on the course of World War One and the subsequent 20th century.

Dr Tom Thorpe [00:02:54] So before we get into the detail, could you give us a brief ... overview of the central narrative of your book?

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:03:01] Well, the book begins in the summer of 1914 and ... sets the stage of what's going on in America. And in this book, I chose to tell the story through three seminal characters, former President Theodore Roosevelt, who in 1914 was really on the downside of his career at that moment, was ... floundering and had lost his popularity influence. The current president of the United States, Woodrow Wilson. And someone who is probably not as well known as he should be - the social reformer and social worker, Jane Addams. These three figures were also important from my perspective, because they were very significant figures in the progressive movements in the United States in the early 1900s, which was a reform movement ... moving the country to the left and ... trying to address the current problems in American society. In the early 1900s, the urbanisation that's going on, the immigration and the the massive industrialisation.

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:03:59] So Roosevelt, Addams and Wilson were all part of that movement. Now I use them in this book to tell the story because they all knew each other very well. They respected one another, all are very well-known figures, but they all had a very different perspective as to how America should respond to the Great War. They all realised it was a very important, unbelievably significant development that was going on. Roosevelt so wanted to be in the White House right now while this was happening and it was killing him that Wilson, the man he absolutely detested, was calling the shots and deciding American foreign policy during this conflagration. So that's where the book begins in the summer of 1914, where America already has to start making decisions. Now, Wilson in the White House basically says, we need to be neutral in thought. And indeed, right now we can't take sides, which, of course, is going to be ... a ridiculous view to take because Americans are naturally going to take sides when this war begins and begins to unfold. But that is the initial gut reaction of the United States in 1914 is - let's stay out of it as much as we can. As the years evolve and as the war goes deeper to 1915, 1916, you're going to start seeing different viewpoints as to what direction we should go. Addams, for example, is someone who believed the United States major goal should be to find a way to bring the combatants to the peace table - somehow. That's what we should be doing at all times. She was a pacifist, but not necessarily from the perspective of a, you know, non-violent pacifist, was more of an internationalist, believe that it was archaic in the 20th century to be fighting these incredibly bloody wars when why can't we find a way to just bring them to the table, get them to talk, at least to see if we can work something out?

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:05:49] And Roosevelt is going to believe that America has to play some role in this war. At the bare minimum, we need to beef up our military. The United States, which is hard to believe, but when the Great War begins, we had an army of about 100,000. I mean, it's a pathetically small army. And Roosevelt's going to say we must build up our forces. We need to put our Navy back where it was - I think the Navy was third or fourth in the world in 1914. He believes we should improve our Navy, and he believes that ultimately the United States will have to get involved in this war, if only even to show our mettle as a nation.

Dr Tom Thorpe [00:06:23] Why did you write this book?

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:06:24] I wrote the book because I felt that World War One, at least again in the United States - not in the UK, I'm sure, really gets, I think, the short shrift as far as historical studies and public knowledge - I feel it's so important and so interesting. And again, as I've tried to make this point in the book and even in talking about the book, that the decision of the United States to go to war, I believe, changes so many things. I mean, certainly I think it did have an impact on how soon the war actually ended and certainly how the peace was ultimately hammered out at Versailles. I think if the United States doesn't get involved, there's still there's all kinds of alternate scenarios, what might have happened as far as the war is concerned. So I think it was a very, very important decision for the United States - and a very important decision for us committing troops across the seas. It was it was almost unthought of, even when we go to war in April 1917, there were many Americans who believed, okay, we're at war, but there's no way we're going to send troops to Europe. That's that's unfathomable. That's hard to believe that we're not when within years of a million, I think, if not more million American soldiers in Europe. So - it is a great game changer for American foreign policy. And I think it's just a really important part of our story in the United States that has been forgotten and deserves to be remembered. And I think also these three individuals, I mean, Wilson, Roosevelt and Addams, are very important figures in the early 20th century in the United States, represent different strands of thought. And they all are trying to push the country in a direction that they believe is the right way - they believe will have significant ramifications in the future. So I think you see this very passionate back and forth - arguments and discussions between these three during this time, each of them trying to see that their perspective is followed because they believe that if it's not, it could have grave consequences for the United States, if not the world, in the future.

Dr Tom Thorpe [00:08:20] And before we commence into the into the debates and discussions that led up to the United States declaration of war in April 1917. Could you just give us a bit of background information on the domestic situation in the USA at this time? What was the socio-political situation that Roosevelt and Addams and Wilson were ... dealing with and what type of factors informed their decisions?

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:08:44] Well, it was the 'progressive movement' in the United States. I mean, the country was was leaning left definitely at the time - when the war broke out. And I think Wilson's administration - Wilson, had been elected in 1912. Roosevelt had had been two presidents before, Wilson and Wilson. Roosevelt actually tried to run again in 1912 on a third party ticket and was defeated. But Wilson's administration, you know, Wilson came in to the White House in 1913. By the summer of 1914, when the war starts, he had a fairly successful domestic agenda - politically and certainly passing legislation that was that was on the liberal progressive side. I think Addams was fairly happy with that. The country seemed to be happy with that. So the country in that sense was fairly, I'd say, fairly united as far as domestic policies are concerned. Now internationally it's a different situation. I think the Eastern Seaboard of the United States was much more connected to what's going on in Europe, felt the war was much more important and was much more affected by some of the issues of American trade and travel, which will become paramount as far as affecting American policy when the war begins.

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:09:53] Roosevelt, as I said, detested Wilson, and Roosevelt had been out of the White House since 1909, and by 1914, he's probably at the lowest ebb of his career. He had tried to establish a new third party called, interestingly enough, The Progressive Party, and he had run on a third party ticket in 1912. But by 1914, when the war has just begun, that party is not achieving what he hoped it would achieve. I think he had hoped that the Progressive Party would ... be like the Republican Party. The Republican Party in the United States began as a third party, and that eventually became the second party of our two party system in the United States. So I think Roosevelt was ... hoping that his organisation, the progressives, was going to turn into a third party, but he soon discovered it was not. So he's ... floundering politically in 1914, and the country doesn't seem to be listening to him. And he's going to pick up the mantle for what he calls 'preparedness'. Meaning the United States - needs to be prepared. And he's going to very emphatically begin to speak out about the Belgium invasion - the German invasion of Belgium. He is going to come to believe that Wilson should have protested strenuously about that invasion and that the fact that he did not was it was a grave mistake. Now, of course, when the invasion occurred, Roosevelt and most people didn't say anything. In fact, I think Roosevelt has a quote in my book where he said something like "When giants wrestle, inevitably those beneath them are going to get stepped on" something like that. Meaning like this is what happens in war. Other countries have done this during war and the Belgian invasion is unfortunate, but there's absolutely nothing we should do about it. But within a few months - and Roosevelt always traced it to when it was a Belgium group that came to the United States in the fall of 1914 - and Rosa had talked to them that that was his ... eye opener as far as what had really occurred in Belgium and the atrocities that had occurred. He comes to believe that Wilson had botched that, and he soon comes to believe that Wilson had botched just about everything as far as the the war was concerned.

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:12:03] As for Addams, her belief is, you know, she's very upset because as a 'rock-ribbed progressive reformer' who's involved in just about every liberal cause domestically and around the world, particularly women's suffrage for big causes, she sees the war is going to roll back all the good, positive reforms of the last 20 years; that nations around the globe are going to be ... under the control of the militarists, and there's going to be much less attention paid to reform issues. So she believes that as a ... as a progressive and as as a reformer, that our role needs to be to find a way to stop the slaughter. And she's going to get involved very early on, starting a new organisation called the Women's Peace Party - which is the first women's peace organisation of its kind ... in the United States. So that's going to be her initial involvement in the war.

Dr Tom Thorpe [00:12:56] So your book looks at the perspective of these three prominent US newsmakers, as you point out, Wilson Roosevelt and Jane Addams. Why did you take this approach rather than maybe a conventional ... chronological history, maybe of events, rather than ... looking at it through the eyes of these three key players?

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:13:15] I think from a readers perspective, it's more interesting - these three are involved in most of the important episodes, so you can ... use them to tell the story ... of the .... main events. But ... on the other side, you can take it down to a micro-level of looking at these individuals. And I think following individuals makes it very interesting.

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:13:38] ... In this book, I also have a number of secondary characters too: you have these three major ones and then I also throughout the narrative thread in different individuals. For example, there's the story of James Norman Hall, who was an American - and some of your listeners might find this interesting. James Norman Hall, who enlisted in the British Army in the fall of ... the summer of 1914, right when the war was beginning. He pretended to be English, and of course they knew he was not, but they took him as he was ... in the British armed forces for about a year. And I used his letters ... and he wrote a number of letters home to his friends and family, telling of his experiences, which are absolutely fascinating. You see his - you hear about his training and then when he goes into combat. And interestingly, for Hall, he eventually was discharged in 1915, late in 1915, when his father was sick and he came back home. Then he wrote a book about his experience, which became a bestseller. Interestingly, Hall later joined the French and then served with the French Lafayette Escadrille later on. And then when the Americans get involved, he served the American army. So he was in ... three different flags during the war - wrote many, many letters, very fascinating stuff, some which I used in the narrative. And then later on some of you might recognise his name, he became a famous author, he wrote 'Mutiny on the Bounty'. So that's an example of a secondary character who's ... woven through the narrative.

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:15:02] And then another interesting person I spent quite a bit on in this book is Wilson's advisor, a guy named Colonel House. He really was not a colonel, but he was someone who never had a title in the administration. But he was so much involved in just about everything. It's almost like Wilson didn't do anything without talking to House first. And from a historical perspective, he's particularly interesting because he kept a diary for years. Every night he would dictate the diary. So he was he was involved in just about everything. Wilson used him as ... a super ambassador. Wilson sent him to Europe, where he met with just about everyone. All ... the higher ups in on the allied side. You hear about his meetings with with the King, with Lloyd George, and I mean, conversations back and forth. What happened with House, is that House was supposed to be following what Wilson wanted him to do is supposed to represent Wilson's views as far as the war was concerned. But House started to just simply ... doing his own thing and so making .... great promises about American involvement in the war and things like that, which Wilson didn't quite know about until much later ... and later on at the Versailles Conference, House is going to be doing the same thing. And finally, Wilson will wise up and ... Cut House up off permanently. But again, that's another interesting story that's threaded through the narrative. So I think for readers, to answer your question, it's often more interesting, and easier to follow when you're writing a book of this kind, if you can write about people rather than simply do a straightforward narrative.

Dr Tom Thorpe [00:16:36] And that's a very nice segway into our next question. I wonder if you could tell us a bit about the background of the three main players and how they saw each other.

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:16:45] So I'll start with Jane Addams because she's she's probably the least well known. It's interesting because even at this time of World War One, she was well known all over the world. She had she had connections all over. Everyone in Europe knew her. She had many, many, many British friends, particularly in the suffrage movement, where she was intimately involved. But Addams was someone who grew up in the Midwest as a child of privilege, had money, but she was someone who couldn't really find herself as a young woman. She was very, very smart. She went to college. She thought about becoming a doctor. That really [ ] And actually what did ... push her in a different direction was when she came to London, saw one of the first settlement houses. These settlement houses were usually located in poor sections of the city, be they in Europe or United States. And young men and women would live in these houses and ... provide social services. So Addams saw one in London, I think it was called Toynbee Hall, if I remember correctly. But anyway, she came back to the United States, decided to set one up in Chicago called Hull House, became very, very successful. Soon, the entire country was writing about the great things that she was doing at Hull House. She became a national figure in the late 19th century, and then she became just about involved in every reform movement. I mean, she was also a prolific writer, and what really made her famous was when she wrote an autobiography called 20 Years at Hull House, which talked about her experiences at Hull House. So by the time of World War One, she was a very well-known figure who was looked on by many Americans as almost ... an American saint, because she did all these wonderful things. But they tended to overlook the other side of Jane Addams, who at times espoused very radical views. And when she starts espousing some of these views during World War One about peace and things like that, the public will turn on her to a great degree, which will be very difficult for her. So that's a quickie - a quick and dirty look at Jane Addams.

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:18:47] Wilson in the United States these days ... has a bad reputation, mostly because of his racial views. Wilson was a child of the South. He grew up in Virginia. He grew up during the Civil War. And he really never lost those racial views. I mean, he was a progressive in many ways as far as race was concerned. He was not ... he never could advance beyond that. So in America right now, we're having you know, there were many schools that were named after Woodrow Wilson just recently in New Jersey. I saw just the other day a high school changed the name of Woodrow Wilson High School to ... another name. So Wilson's a very complex figure. As I say, he grew up in the South. He was an academic. He was the president of Princeton. He was, you know, fairly successful as an academic. And he wrote a number of books on history. And surprisingly, someone in the Democratic Party saw potential in him and said, this guy might be someone we could get into politics. So they ran him for the governor of New Jersey. He surprisingly got elected, performed very well. And then suddenly in 1912, he became a presidential candidate, got the nomination and won. So ... his political story was is quite remarkable where he came from, being an academic to governor of New Jersey to President of the United States, Democrat, liberal - except when it came to race. I mean, his administration imposed fairly strong segregation in government positions - for which he is still rightly criticised very harshly about today. As far as women's suffrage was concerned, he wasn't too keen on that. Women's suffrage people were very unhappy that he was slow on that as well. As far as foreign policy is concerned, the story is he really was not a foreign policy guy when he came to the White House. He was much more interested in domestic issues. And what's ironic is that when he comes in to deal with the Great War, he's he's got to learn on the job. He ... does not have the background that someone like Roosevelt had.

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:20:44] So we'll do a quick segway to Roosevelt's. Incidentally, these three were all born within about the same time period, all meeting between like 1856 and 1860. I think they were all born. Roosevelt again came from privilege in New York. Very, very super smart guy, had health issues as a young man, asthma. He always told a story that he had somehow conquered asthma with physical fitness. But throughout his life, he always continued to ... struggle with it. Even they didn't quite live it out in his writings. He's someone like Addams who wasn't really sure what he wanted to do. He went to law school, really liked being a lawyer. Eventually, he stuck his toe in New York politics, and from there he just rose up the ladder. What made him famous was the Spanish-American War with his group of volunteers, the Rough Riders and their story of charging up San Juan Hill with some of that story is a little bit fudged, but it made a good story, made him famous. And from there, that was his jumping off point into national politics, got the vice presidential ticket in 1900. And then when President McKinley was assassinated, suddenly Teddy Roosevelt's president and he's only 42 years old, he was the youngest man to be president. And that's Roosevelt's, you know, how Roosevelt got to be president. He had a very successful term - two terms in office, first atfter McKinley, then he got elected on his own. And Roosevelt was someone who was a larger than life figure. People liked Roosevelt, he was so such a recognisable figure. You're never at a loss for words. Very colourful, brilliant. Someone who ... had a photographic memory and he knew something about just about everything. It's interesting, I read in doing the research for this book, you see the millions of letters he wrote. I mean, I'm exaggerating slightly, but he wrote so many letters. He kept up a correspondence all around the world and on all different subjects. He knew something, just about everyone on just about every topic. He had been a historian. He was interested in natural sciences, geology, everything politically. As I said, he was a Republican who moved to the left. And that was one of the reasons why you end up forming his own party, the Progressive Party, which we already mentioned earlier. So that's a get a quick background straight. They all knew each other. Roosevelt and Wilson had been, you know, cordial to one another at one point, but they eventually came to detest one another - which is ... of a big part of this book of the rivalry between these two. Adsams was friendly ... with Roosevelt at first. (She) was involved in the Progressive Party with them, but would split with him over the issue of ... the Great War, and she'll instead move towards Wilson and become friendly with Wilson. So three of them are enmeshed throughout this narrative and again, very much trying to influence one another and push each other in the direction that they see is the proper direction for America to be pursuing at this time.

Dr Tom Thorpe [00:23:31] So what were their respective positions on how the U.S. should respond to the war once it broke out in August 1914?

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:23:40] I think Wilson's desire I mean, he did say, you know, America shouldn't we should not take sides. You know ... his greatest fear was that the American public would lose its emotional ... control. I mean, Wilson himself was very big on maintaining what he called self-possession in himself. And you don't lose ... that. He was always afraid the United States would lose that self-possession and that we would end up making a decision we might regret. And he felt his job initially was to keep a lid on America's emotions - especially in a country which had such a large immigrant population. You know, we had many, many German-Americans in this country, and many of them are going to naturally, they're going to root for the fatherland. I didn't mean they were necessarily disloyal Americans, but if they were watching from from afar, they were going to root for that side. Then you have the Irish - there were many Irish who were of course, they were also going to root for the German side - because they were not happy, you know, with England. On the other side, you have many Americans of English descent, of French descent who are going to root for the allies. So there was that split in the United States. And I think on the East Coast there was a very strong pro-allied position, especially in the newspapers, in the press. But in other parts of the country. I don't think they cared one way or the other. You have ... The great Midwest, which was ... yeah, this is far away from us. The South, same thing. On the West Coast they're more concerned about things like Japan.

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:25:12] Much of the country, I would say ... was truly neutral. There were some who were passionately pro one way or the other. Both sides, the Allied side and German side will try to win the PR battle in America. In other words, do what they can to make sure that Americans take their position. The Germans pretty much blew that very early on. I think with the invasion of Belgium many Americans who were maybe didn't care one way or the other were appalled by that - by the brutal invasion and instinctively began to take the Allied side.

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:25:46] Now, did taking the allied side mean want to go to war? No, I would say not that time. They would certainly prefer the Allies to win the war, but they were not - most Americans, at least in 1914, 1915 - were not necessarily ready to go to war. So that was Wilson - Wilson's view was keep America's emotions under control. And then at some point, the Allies or both sides will come to America, as you know, (he acted as) - a disinterested bystander to assist in the peace process. Because we didn't take sides one way or the other, we will be able to ... play an important role in the peace process - this is what Wilson was envisioning.

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:26:27] Now, Roosevelt believed that was probably nonsense. And you even have letters early in the war where Roosevelt is getting letters from Rudyard Kipling, I think in 1914. Rudyard Kipling was, of course, one of Roosevelt's correspondents. Kipling saying something like "the more money and treasure and bodies and death that each each side suffers, the the less likely they're going to want to have any outsider be involved in the peace process". And I think Roosevelt realised that early on. He said there's no way the United States is going to be be able to participate in the peace process if we don't if we're not involved in the war. I think what he said said the best we would be able to do would be act as some ... "go and fetch" type thing. In other words, we could fetch the two sides together and then be kept outside the door while they hash things out. That's all we're going to do because we're not doing anything in the war. So he thought what Wilson was doing was was naive at best. So Roosevelt believed, certainly, again, that we need to have a stronger military. And particularly, he believed that we're not in a position to do anything around the world. If we believe Belgium has been brutalised, we can't even do anything because our military is so feeble. So what can we do anyway? The United States is not doing enough to put our military into a 20th century footing. He's very angry that in December 1914, a few months into the war, where there is talk on Capitol Hill of trying to see where we stand in the United States militarily, and address that deficiency, Wilson pretty much squelches that, says it's not time to talk about, you know, if there's a war, sometimes we'll get ready but right now, it's not the time to be talking at all about preparing. And Roosevelt's absolutely and absolutely incensed by that.

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:28:13] What changes everything is the Lusitania sinking. When that happens, I think that's a dose of reality for a lot of Americans. And then I'll just quickly pivot to John Adsams.

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:28:26] Addams, as I've mentioned, starts the Women's Peace Party, which is trying to do what it can to at least get peace talked about in the United States as far as to find a way to, again, bring the combatants to the peace table - and prevent the United States from getting involved militarily. She's also plugged into the international peace networks that do exist, such as they are at the time. In fact, she's going to go to The Hague in 1915 as part of a delegation of women. It's going to be a women's peace conference in The Hague in 1915, which is actually a very remarkable gathering of women, even from some of the warring countries, although the British did what they could to prevent British women from going to that particular meeting. And after that meeting is over, there's going to be a vote made at the Congress to send representatives from the meeting to the heads of state of the warring countries. So Adams and a few others will go to Germany, to France, to Great Britain and talk to the heads of state, you know, trying to get them to say, are there things that both sides can agree on that can somehow bring about either a cease fire or something to stop the slaughter? And I want to say this also. The Addams was no, she wasn't naive. I think she was someone who believed anything is worth trying to stop the slaughter, even if some of it may seem far fetched or pie in the sky. She's someone who also very much thought a conference of neutrals could be a good idea, meaning let's bring the neutral countries together ... as a beginning of a peace conference. And from there, use that to bring the warring powers together to talk. So that's really, I think, the mindset in the early months of the year, of these three early months of the war, of these three individuals.

Dr Tom Thorpe [00:30:14] So how do they ... change their views as the war progresses? I'm thinking about events like the Lusitania, you mentioned. Unrestricted submarine warfare by the German navy, but what about the Easter Rising as well that happened in Dublin in April 1916. How did these events shape ... their respective positions on America's duty and role in the war?

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:30:35] Well, the Easter Rebellion is interesting in that in many cases, it turned a lot of Americans, at least temporarily, against the Allied side. One thing I was surprised in my research for this book was there was considerably more ambivalence against the Allied side than I anticipated. Because ... We always tend to think of serving during World War Two where there's this great close relationship between the United Kingdom and the United States. Even before we got involved in World War Two. In World War One, there were a lot of sensitive issues, the interference of the British with American trade. You know, Americans believe they should be able to trade with with neutral nations. Of course, the British believe, well, your trade with neutral nations, but they're reshipping it to Germany so we have ... the right to stop that trade and and confiscate cargoes, and we will eventually compensate you. But Americans were very angry, some Americans were very angry about that, you know - the cotton growers. So there was to some degree some backlash. And so the Easter Rebellion was an example when news of that came to the United States, there was a great deal of anger. The letter I have in my book, where Roosevelt - he got a letter from, I can't remember which British correspondent was who said, yes, it was, the Easter Rebellion was a much more - much nastier business than the public even knows about. At the same time, in the summer of 1916, there were a lot of controversy about the British censors reading American mail and opening up mail. There was fear that, Oh, well, the British are doing this so they can get American trade secrets. So there was, you know, surprising bits of antagonism. And even I read I went into this I read a lot of the Foreign Office papers and you read a lot of the discussions about America - i's always "we have to placate America". We must placate them. We don't we don't think they're going to go to war with us, but they can make things ugly for us. They could try to break the blockade or something like that.

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:32:30] So there's a lot of touchy, touchy touch and touch and go feelings on both sides. And particularly in 1916, where the German situation with the United States seemed to be quiescent at the time - the Germans had agreed to pull back on on the submarines with the Sussex Pledge. They said, we're going to do cruiser warfare, meaning ... we will give advance warning. We will you know, we will make sure everyone's safety is provided ... for civilians and things like that. So that was at that point, things were fairly calm, I would say - there was a little bit of backlash against against the English, but I don't think there was ever any serious antagonism because of the amount of money the United States was making trading with the allies. I mean, they were making enormous sums of money, particularly ammunitions. A nd of course, loans. And the British came to rely on those a great deal by 1916, 1917.

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:33:24] But coming back to your question - with the Lusitania. I think Wilson came to realise that ... the American military would have to be beefed up and following the Lusitania in the summer of 1915, you start having more and more, okay, there's going to be more and more discussion of Wilson going into the preparedness camp. But of course it takes a long time for legislation to get hammered out until 1916. And that was something Roosevelt kept saying over and over again that, you know, we can't just build up. We can't just snap our fingers and get an army together. It's going to take a long time. And that ... was very ... far seeing by Roosevelt, because when America does get involved in war in 1917, you know, it does take us a while to be able to put a substantial force in the field in Europe. And had we started earlier, as Roosevelt himself said, we would hafe been able to deploy a substantial force in 1917 rather than really more in 1918 as the American presence on the Western Front - much more substantial.

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:34:32] So I think Wilson was forced to change his views, but he's certainly not ready to go to war. I think Roosevelt was probably, saw war is inevitable. There's a quote from him after the Lusitania where he says something, in fact, "there are worse things than war". In other words, there's you know, what are we ... as a country, you know, if we cannot back up our promises and if we are going to be humiliated by Germany - war is actually a better solution. Now, not many Americans took that viewpoint in 1915. But I think, as I said, Wilson is going to be moved gradually, more and more to that view. And I think also Wilson will be moved more and more to a belief that America has to be involved if he's going to achieve anything as far as peace is concerned and remaking the post-war world.

Dr Tom Thorpe [00:35:22] So why does America declare war on Germany in April 1917?

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:35:27] Well, if we back up a little bit - in the fall of 191 the Germans were starting to get a little antsy. I mean, they were probably ahead at that point in the fall of 1916, or maybe slightly ahead or at least holding their own. But they knew they could not win a long war, and they were hoping that Wilson would issue some sort of. Okay, guys, let's get together, you know, bring the parties together for some sort of peace conference. Ideally, a peace conference that would allow Germany to keep all of its gains. But that's what they they were hoping that Wilson would somehow bring -he would act as the prime mover to bring both sides together for some sort of conference - because they felt they could not win a long war. And the war was going on and on. They probably weren't always. So this would be a way to wrap up the war nicely with with them winning it, or at least getting the better, better end of it. So there's all these back and forth of these letters. You know, there's another figure in this book is the German Ambassador Bernstorff in Washington is a very interesting figure. He was probably the only German who realised how important the United States was in this picture. In Berlin I think a lot of them didn't really get it. They thought America wa like "all they care about the money". All they care about money. They called the United States "Dollerica". Bernstorff in Washington was like, "no, you're wrong. This country has inexhaustible resources. And if they get involved in the war, we are done". He tried to tell them that, but they did. They just did not believe him. So Bernstorf is in Washington trying to do all these little machinations, but he's told until the election is over, America is not doing anything. But on the other hand, the Kaiser also pretty much was saying, if America doesn't do something soon, we are going to resume unrestricted submarine warfare. So you'd better do something soon to bring the power to go to find a way to end the war. So that warning was also hanging over Wilson's head. Now, Wilson, you know, read that, you know, didn't ignore - he wasn't going to be bullied by the Kaiser. But it was another data point to consider.

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:37:30] After the election is over, the election was very, very close - I won't get into that here - Wilson realised that, yeah, we're in a very difficult situation because the German's current good behaviour, as far as the submarines are concerned, it is not going to last forever because they want to win the war soon because they know a long war is going to doom them. So Wilson starts working on a peace note in the fall of 1916 as a way to ... try to find a way to ... bring the sides together and get them talking and to be able to at least get a cease fire. While he's doing that, the Germans get tired of waiting for Wilson to do something, and they issue their own ... half hearted, half-baked peace offer, which of course is promptly rejected by the Allies. And unfortunately for Wilson, who didn't know they were going to do this, his own peace attempt comes out, I think, a week or so later, which, of course, the Allies were very unhappy that he did this. They felt that he should ... not doing this right now. But Wilson felt this was the best opportunity, and he also felt this ... was, sort of, a Hail Mary pass toBprevent America from getting involved in the war, because if peace is not made soon or it's not a peace treaty or a peace conference is started, the Germans are going to resume unrestricted submarine warfare. As it turned out, Wilson's peace move in December 1916 accomplished nothing. Neither side was interested. Both sides believed that they could win, and they both expended so much blood and treasure by that point. There's like no way we're not. It's like you're hanging on. We're not going to let go right now. We're not we're not interested in this right now. So Wilson didn't give up. In early 1917, he made his famous Peace Without Victory speech ... saying that America - we have a right to be involved in the peace process. And we, you know, we also are going to take part in some sort of future League of Nations. And if we're going to do that, we have a right to be involved in the peace process that is eventually going to come for this war. But the peace that should come should be a peace without victory. It was a very well-received speech in the United States. But again ... across the pond, it was not received so well. You know, again, it was a case of ... "who (does) Wilson think he is" - he should be putting out things like that. At the time that Wilson made the speech, he thought that the Germans might be receptive, but he was wrong ... I wrote this in the book, that the Americans didn't have a great idea of what was really going on in Berlin. They didn't have the spies - the Germans had but spies in the United States, the Americans needed spies and Germany didn't really have them. But the German ' higher ups' : the military, the Navy, had made the decision for unrestricted warfare - a resumption of unrestricted warfare in early 1917. And once that decision is made ... the die is cast. When Wilson is informed of this, he immediately severs ties with Germany. The German ambassador, diplomatic ties, the German ambassador is sent home. The American ambassador in Berlin is sent home. And at that point, everyone thinks that war is probably going to come. You know, there are some articles at that time saying every time two major powers have severed diplomatic ties almost. It always has led to war in the past. But Wilson still hesitated. He thought again there might be a way out. He figured it was up to the Germans ... because the Germans, up to this point, had done everything possible to keep America out of the war. But at this point, they had decided that we have to go for broke, we have to release the submarines ... if it brings the Americans into the war. So what? Because it will be too late. By the time the Americans can get an army together, we will have won the war. We will have starved the British into submission. And our great plan has worked. And of course, that plan was was completely wrong. But that seemed to be the one idea that was ... pulsating through the German military and navy at the time was that we can win the war this way. And who cares about the Americans by the the time they get up to snuff, it'll be too late.

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:41:39] So Wilson was thinking, okay, maybe the Germans will continue their good behaviour until they do something right now. We'll stay neutral. The next push, however, becomes .. .at least arm our ships. You know, so we do an 'armed neutrality' ... And that becomes a huge fight on Capitol Hill, which I won't even bother to .. They can't get that through either.

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:42:03] Eventually, there are two things that are going to push Wilson finally in the direction of of going to war. One of them is the famous Zimmermann Telegram. This was the a telegram sent from Berlin, from the German Foreign Office to the Mexican Ambassador, basically saying, well, looks like war with America is likely to come. If it does come, we would like Mexican assistance and ... let's dangle out ... If Mexican ... wants to help we'll ... give them the opportunity to ... win back lands they lost to the United States .. and parts of states, like Texas and Arizona and New Mexico ... and things like that. It was an absolutely ... preposterous scheme. Cooler heads in Berlin should have put a stop to it.

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:42:55] What I've read in my research, one of the reasons that it ... got through was that this was in the midst of the decision for unrestricted submarine warfare where there was chaos going on. So this this made its way through this scheme. The British intercepted; 'Blinker' Hall and his codebreaking team intercepted it. They sat on it for a while because they didn't want the United States to know they were also intercepting some American diplomatic cables as well. Then eventually they ... disclosed it to the United States. It went to Wilson and then Wilson allowed it to be leaked to the American press, which, of course, resulted in great anger in America over this - even though, again ... people when they thought of it, they realised it was a crazy cockamamie scheme. It had no basis in reality. But the idea of trying to ferment war on the American Mexican border ... was simply crazy.

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:43:53] Now, at the time, I'll just quickly, mention this. There was a great deal of tension with the United States and Mexico. Mexico was always a thorn in the United States side for a while, was an unstable country with a civil war going on. So it was not surprising that the Germans would think, okay, if we can get the Mexicans to tie up the Americans on the border, that will prevent them from sending troops to Europe at some point. But anyway, the whole thing was very ill conceived. It was another backlash, a great deal of anger. Wilson, of course, was appalled. So that was something, again, nudging him in that direction.

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:44:30] The other thing that pushed them in that direction, I think, was his belief by early 1917 that he had to be involved in the war. There's a very dramatic scene in the book where Addams comes to the White House in early 1917, and she's trying to get him to find a way to get out of this war, to keep out of the war. And Wilson tells her, "if we don't get involved in this war", in so many words, "I won't have a place at the peace table. I won't be able to get in even by a crack in the door". So he's almost saying to her that I can't do the great things I want to do with remaking the world and being involved in the League of Nations, unless America is involved in this war. So I think that was another very important thing that motivated him.

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:45:15] And finally, they were just. It became clear the Germans this time we're not going to pull back to appease the Americans. In late March, you had several American ships that were sunk, three in very rapid succession. And at that point, the die is cast. Wilson is going to ask for war. And Wilson, it was something he did not he was not someone who glorified warfare. He's not like Roosevelt whose greatest desire was to go to fight. Roosevelt was hoping - he was trying to raise. He has actually been working on raising a Division to go to Europe to fight in this war. So he is so itching to go over, even though he's overseas, he's almost 60 years old, he's not in great shape and he wants to go over and fight - because that's a big part of what Roosevelt was all about, you know, manliness and and that type of thing. Whereas Wilson was not at all inclined in that direction. He was not someone who was ... wired that way. And there's even some diplomatic correspondence with the French, with one of the French diplomats is saying, like, you know, Wilson supposedly told me that he was afraid to go to war because he felt he would be held responsible by God for it, for the killing of all these young men he was going to send to their deaths. Wilson, of course, was was a son of a Presbyterian minister. So I think Wilson was ambivalent up to a point, but then came to realise, for me personally, and for the nation personally, the best decision is to go to war. I think when the vote for war, you know, the Wilson makes his speech asking Congress to declare war. Then you have the debate in Congress and the vote in Congress was 373 to, I think 50, which may sound like that's really not that much opposition. But what people said at the time was if it had been a secret ballot, it would have been a lot closer in Congress. In the Senate, it was 82 to 6, I believe was was the vote. But there was considerable ambivalence in, again, the Midwest and the South about agreeing to participate in this war, even at the last minute. And there were some who believe that Wilson could have found another path, rather, to go to war in April 1917.

Dr Tom Thorpe [00:47:27] And may be considering those other paths. Was the declaration of war on Germany in April 1917 inevitable, or were there other possible outcomes on it? I know its slightly counterfactual for a historian to consider, but sometimes these things are worth thinking about.

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:47:42] I think definitely. I think Wilson probably could have said, we're going to we're just going to continue to be neutral. We will arm our ships. And if they you know, they skirmish with with German submarines, so be it. We ... continue to supply the allies, but we are not going to commit American troops for this because of the number of Americans who have ... been killed in these submarine attacks. It's less than 200 or whatever it was. And this is not enough to warrant going to war. I think he could have done it might have been strong opposition, but he had just been elected President so he didn't have to worry about that issue. He might have politically worried about the Republicans and Roosevelt who had returned to the Republican Party by this point. There was a lot of talk that Roosevelt was going to run for President in 1920, which would be the next election after the most recent. But I do think it was possible, certainly for Wilson to have simply said we're going to continue the status quo. Addams, as I said up to the last minute, had she had gone to him, tried to get him to consider alternate paths, she was still pushing the conference of neutrals as a first step towards a peace conference. Why can't we get together with like Spain and Sweden and things like that and have some sort of conference which will bring eventually bring the other nations together? But the thing about Wilson is ... Addams thought he was much more of a pacifist than he actually was. And he really was someone who ... for him, he came to realise that his view and his vision for the future could best be realised by the war, no matter how distasteful it was. But I do think there were alternate paths to follow in 1917.

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:49:29] It's interesting because I quoted it in the book, but Bernstorff, the German ambassador, after the war said, you know, Mr. Wilson wanted democracy in Europe. And perhaps if America had stayed out of this war, the war may have been fought to a stalemate. And perhaps, you know, things could have been very different in Europe after the war, very different in Germany. After the war. Bernstorff was convinced that German soldiers returning from such a war would never have tolerated the monarchy much longer, that there could have been a democracy of some kind. These are again, counterfactual history, but it is interesting to consider what might have happened if Wilson had decided not to go ... and how the war might have unfolded.

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:50:15] It's also possible, I mention this in the book as well, that maybe the two sides do fight to a stalemate, but that would probably mean they would have both marshalled up their forces again and fought it out a few years later - unless the League of Nations had been established and was prepared to intervene to stop another global war, which we saw that League of Nations failed to do that in the 1930s. But of course, that was without American involvement. I think if Wilson had managed to get his League of Nations somehow and with America in it and willing to throw its weight around, that could have been another another possibility of how events might have been different.

Dr Tom Thorpe [00:50:49] And my final question is, where can people learn more about your work and get the book?

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:50:55] You can go to my website, which is https://neillanctot.com. You can also go to the Penguin Random House website ... and you can find my book and certainly on Amazon, which is ubiquitous these days around the globe, so I'm sure the book is available through Amazon or your local bookstore, whatever. I think there's a little bit of something for everyone in this book, you know, those who are interested in the war itself. I think it's also, I think, a snapshot view of life at that time, American life in the early 20th century. You know, there's this little side notes on things like Harry Houdini - Wilson going to see Harry Houdini in the theatre? And and the new movie superstar Charlie Chaplin. There's a Charlie Chaplin craze in America in the middle of this war. So I think there's that, there's the big heavy stuff. And then there's just the story of these three people who tried to do what was right - and often faced a lot of criticism. And I give them all three of them credit for - they didn't flinch. I mean, they kind of stood up to the public and they showed a lot of political courage. Courage, which we need more of today in today's world, I think.

Dr Tom Thorpe [00:52:09] Neil, thank you very much for your time.

Dr Neil Lanctot [00:52:12] Thank you for having me.