‘A serious scandal bringing humiliation and disgrace upon Australian Forces’ – The Australian Graves Service

The recovery of the British and Dominion dead began in late November 1918. The Canadians began to search the Albert/Courcelette area and Vimy Ridge, whilst the Australian Graves Detachment (AGD) tackled Pozières and Villers Bretonneux.[1] These two nations handed over the exhumation task to the British Army in mid-1919 as they demobilised. This article considers the scandals ‘bringing humiliation and disgrace’ on the Australian Graves Service (AGS) that remained in France after that point,[2] and which resulted in two Courts of Inquiry. Australians have been ambivalent about discussing these scandals. Historians Cahir et al assume a light touch, concentrating on one officer, and seemingly blaming stress;[3] journalist Marianne van Velzen provides a rather repetitive, sensationalist and sometimes fanciful approach.[4] Writers have, on occasions, used the terms AGD and AGS interchangeably, which confuses their different functions. This article seeks to provide a thematic examination of the problems of both services and place the personal and cultural aspects in the context of organisational issues. It ends with the matter of the Fromelles mass graves, which has attracted much interest and comment, e.g. on the Great War Forum.

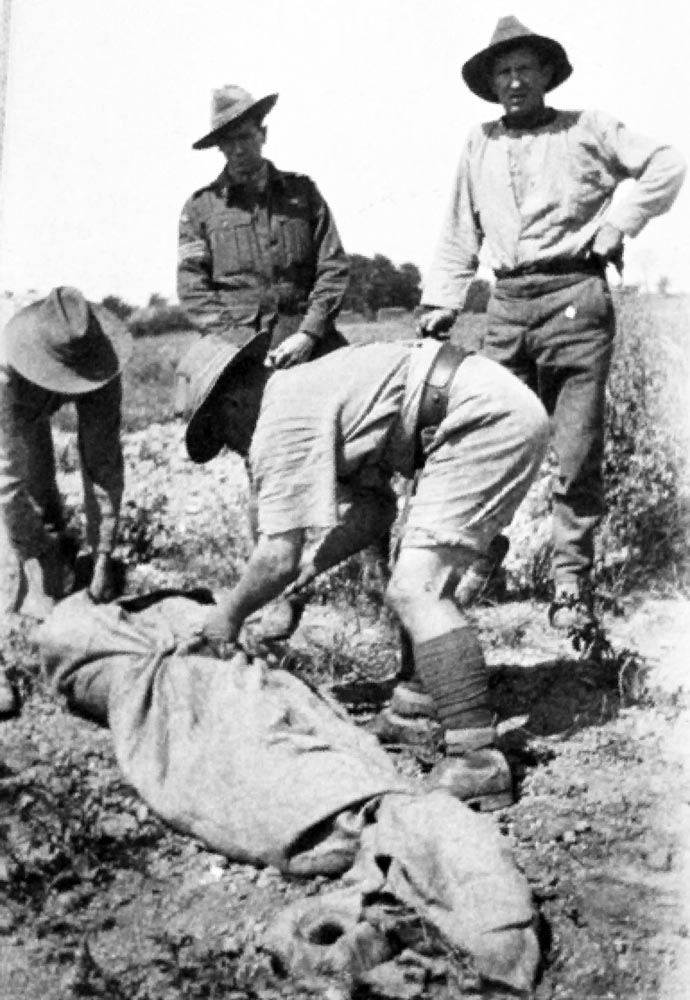

The Australian Graves Detachment

The Australian Graves Detachment comprised 1,050 individuals. Officers and HQ staff were selected, the rest were volunteers, a number of whom had never previously served on the Western Front. The AGD existed from March to August 1919, and conducted 5,469 exhumations and re-burials. The recovered were interred in Adelaide and Crucifix Corner Cemeteries, Villers-Bretonneux Military Cemetery; and Heath and Dive Copse Cemeteries.[5]

The unit was commanded from March 1919 by Lt-Col John Eldred Mott MC and bar, a mechanical mining engineer who had served with the 48th Battalion and had been wounded and made prisoner of war at Bullecourt on 11 April 1917 (escaping after a year). Re-joining the 48th Battalion from Senior Officer School in January 1919, moving thence to the AGD, he required the 'distinct personality' described during the course.[6] Private William Frampton McBeath, a 19 year-old coach builder who attested in June 1918, arriving in France in January 1919, wrote in April that year:

I think they have got the roughest lot of officers they could find in the AIF with this unit, and by jove they want them it is the roughest mob I have ever seen, they would just as soon down tools as not. Although we have only been going a few weeks we have had two strikes, we refused to work until we had better means for handling the bodies, had better food and cut out all ceremonial parades.

What weight should be given to Private McBeath’s observations? In respect of his rough officers, Company Sergeant-Major Jack Phillip Mckinney acknowledged the problem, claiming that ‘We’re an awkward crowd to deal with. You can’t tell a damned officer from a private by his manner’.[7] In respect of the rough mob in the ranks, Corns and Hughes-Wilson conclude that whilst acknowledging their undoubted fighting ability, the Australians ‘were, by British standards, woefully undisciplined’, with a ‘cavalier attitude to formal discipline’.[8]

Australian historian Clare Rhoden re-interprets these issues. In terms of officer/man relations she suggests that ‘different expectations about leadership’ in Australian eyes underlay this issue.[9] She reframes discipline matters as a reflection of the ‘explicit egalitarian values of Australian society’, and their ‘attitude to the war as work rather than a crusade for ideals’.[10] If their war was ‘work’, then the use of industrial relations strategy, the strike (sometimes described as mutiny) was logical and, within the Australian Imperial Force, known and effective.[11] Mott understood this well, did not report the strikes and supported an increase in pay. What McBeath observed was, seemingly, par for the course. Turning matters on their head, Julia Smart quotes a newspaper report where AGD Sergeant Sydney Wigzell asserted that it was the very group that McBeath represented, i.e. those who had not endured trench life, who were most dissatisfied with clothing, pay and food.[12] Smart also records that Rose Venn-Brown, an Australian Red Cross worker in France throughout the war, noted drunkenness (an episode of which led to the court martial of an AGD private for wounding with a knife in the aftermath of a fight),[13] and an influx of ‘questionable women from Paris and Amiens’ (a fight with locals concerning these women nearly leading to an exchange of hand grenades). These issues, and more, would rear their heads again.

The Australian Graves Service

The Australian Graves Service, which followed, had an entirely different role, exhumation having been handed over to British labour units (Graves Concentration Units), and Graves Registration Units (GRU – responsible for recording cemetery burials). It consisted of only 75 men (33 transferring from the AGD) covering inspection, checking reburials, monument and memorial cross erection, and grave photography for relatives in Australia. On days when photography was impossible due to light, occasional exhumations of unidentified Australian soldiers were conducted, but in general, as the High Commissioner in London wrote to the Prime Minister in 1921, it was ‘difficult to make clear even to Australians in London that Australian Graves Services have never done any actual exhumation work’.[14] The unit was based in three locations, under the leadership of Captain Quentin Shaddock Spedding, invalided from the 38th Battalion, who after a spell in the Graves Records Branch at Australia House in London had been attached to the AGD in a liaison capacity.

The locations and officers in charge were:

Poperinghe – Chief Inspector of Australian Graves, Honorary Captain (Major in the Red Cross) Alfred Allen. Later, five photographers were attached. (Peripheral was a team of 15 personnel working on battle memorials, based at Peronne under Captain Barden and Lieutenants Pierce and Hylton – in 1920 this became formally part of the AGS).

Amiens – Assistant Inspector Australian Graves, Lieutenant William Lee (ex-AGD). There were two additional personnel, a clerk and a draughtsman.

Villers-Bretonneux – Transport and Photographic Section under Captain Allan Charles Waters Kingston (ex-AGD transport). Kingston’s base also absorbed the Memorial Cross Section from Poperinghe, his command amounting to some 45 men in all.

The first Court of Inquiry

The problems that developed within the AGS which led to the first Court of Inquiry (COI) (30 March to 12 April 1920), can be summarised under a number of headings.

(a) Organisation and leadership

The service was poorly organised and led from the start. Spedding was based in London where there were eight military personnel and 17 civilians dedicated to matters pertaining to the dead. The AGS reported to Australia House, rather than any military authorities remaining in France, and the three sections in France and Belgium had no formal relationship with each other, reporting to London separately. Spedding’s testimony at the first COI gives an impression of his remote management and light touch – on his own admission he travelled to France only four times in six months. His formal instructions only appear to be the four page ‘Notes for the Guidance of Inspectors and Staff, Australian Graves Service’ (date unknown), and a further minute based on a meeting in France issued on 10 December 1919. Kingston in his testimony to the court stated that ‘I have received no written instructions as to what work I have to carry out at any time’. Indeed, the court found ‘no reasonable or definite plan of carrying out the work seems to have been formed’. As with everyone who addressed the court, Spedding denied any extensive knowledge of the problems that developed within his service and hence made no effort to address them.

Spedding claimed in retrospect, that ‘I was not satisfied with the organisation … with the energy of the people in France’. He recommended the removal of Lieutenant Lee ‘who was a source of trouble and a worry to the other officers’. He stated that he had ‘no complaints’ about Kingston, whom he described (mistakenly), as the ‘the strongest man there’. He had complaints with Allen, however, who tended to behave as if he was in charge of the service (Spedding resented his use of the honorary rank major, senior to his own), and who he believed was somehow machinating against him. He regarded Allen as ‘not loyal’. Kingston, alternatively, regarded Allen as in charge in France (which may simply have been an avoidance of his own responsibility, especially as the only matter Allen had any responsibility for was discipline, a responsibility both Kingston and Allen failed to exercise). Allen excused himself, referring to Kingston, telling the court that ‘I had no power to give him any instructions’.

What Spedding had presided over was clearly utterly unmilitary, the equivalent of having three platoons with no present company commander.[15] He was suspended in January 1920 for entering into negotiations with the family of a French nobleman (known to the AGS as ‘the Duke’) regarding the exhumation of his corpse, illegal in any shape or form under French law until 31 July 1920. Spedding accepted money for this potential service, and hence the verdict of investigations into his actions, that he had made a ‘mistake’, was generous. He was told to resign and sent home.

Spedding’s place was taken prior to the first COI by Major George Lort Phillips. Wounded on Gallipoli in August 1915 he had not seen active service again, but was described as ‘an excellent disciplinarian with a knowledge of and sympathy with human nature’.[16] Phillips had been OC of the detention barracks at Lewes, and was disliked within the AGS because of his association with the Military Police (some claiming, bogusly, that he was appointing MPs to roles in the AGS). In his evidence to the first COI Phillips described ‘lack of instructions, want of control from London … hopeless organisation in France’. He busied himself first with sorting the organisational issues in Australia House and this delayed any visit to France to see matters there for himself. There, he placed Captain William Thomas Meikle in Kingston’s vacated position following the COI, and officer commanding the AGS in France. Meikle, a motor mechanic commissioned on Gallipoli, had suffered much illness and had latterly worked in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) records section in London. He had also acted as one of the three members of the examining panel in the first COI (his subsequent AGS job giving rise to accusations that Phillips had sought to influence his judgement with the promise of employment).

(b) Officer in-fighting

Charlie Kingston, a farm hand, had served on Gallipoli and the Western Front and been awarded both the Meritorious Service Medal and Distinguished Conduct Medal at the rank of sergeant at the Hindenburg Line opposite Bellenglise 20-21 September 1918, when ‘he supervised the bringing forward rations and ammunition … done at night time, when the enemy was shelling and bombing all roads incessantly’. He was commissioned second-lieutenant in October 1918.

William Lee, a mining and electrical engineer, had spent his war on the Western Front from early 1916 in the 4th Australian Divisional Signals Company, and had been commissioned in April 1917. He opted to remain in France in 1919 where he expected his wife to arrive and then planned to proceed to Nigeria for further mining prospects. Lee was nearly 46, and the 28 year-old Kingston was promoted captain on 1 November 1919, leapfrogging Lee in rank. Lee thus had a more senior post in the AGS at a lower rank than Kingston. Allen referred to ‘jealousy’ starting at the point of Kingston’s final promotion, and described Lee’s obsession with Kingston as a ‘mental craze’.

The court found that ‘a condition of enmity and ill-feeling arose between Capt. Kingston and Lieut. Lee and became so bitter that these officers never spoke on meeting’. The problem began when Lee accused Kingston of disposing of all his personal possessions when he was setting up his Amiens base. He was further offended by the way in which Kingston paid all the staff, including him. This was carried out in an estaminet in Villers Bretonneux, which Lee would not tolerate as a location for himself, demanding that Kingston deliver his pay to him in Amiens. He described Kingston as deploying ‘harassing methods’ and ‘paltry tactics’. Lee, in fact, had a poor history with money – his service file states that he was recalled to London under arrest in September 1919 on charges involving in late 1918 and early 1919 paying himself amounts of money from unit funds and not entering it in his paybook. The investigation into this simply ordered him ‘reprimanded’. The matter was never mentioned at the COI, this being curious as he had been appointed to the AGS several weeks prior to his arrest. Lee, who described the relations between him and Kingston as ‘damnable’, machinated with the Mayor of Villers-Bretonneux to write a letter of complaint about Kingston, and did the same with a Major D R Osborne (who remains unidentified). Phillips reported to the court that Lee ‘appeared to hold alleged grievances against various other members of the Graves Services, and appeared to go out of his way to work up one complaint after another, many of which were without foundation’. Lee had also fallen out with many of the British officers ‘owing to his tactless method of approach’.

Lee was described by the Department of Defence as ‘a man discredited in himself, his staff and associates … prompted by a vindictive and shameless spirit of revenge.’ This, however, was not the only problem. The work of his section was ‘carelessly and negligently performed’, with ‘no proper control’. The court concluded that ‘he behaved himself in a scandalous manner, was guilty of conduct unbecoming the character of an officer and gentleman, (and) was unfit for the post at Amiens’. Both Lee and Kingston narrowly escaped court martial on grounds of ‘resultant harm of disclosure’. Following his return to Australia Lee continued with lengthy condemnatory letters about his fellow officers in France. He was clearly a man dominated by petty jealousy – a personal flaw. In the absence of proper senior oversight, this flaw ran riot. This would also be the case for Charlie Kingston.

(c) Breakdown in discipline

Kingston would state to the COI that ‘discipline … when I took over was for a week or two very bad. The men were constantly getting drunk and I experienced trouble with male civilians. The majority of the men were a bad lot and very inefficient. They were neither dependable or reliable’. He claimed, without irony, to have weeded them out, yet his neglect of command would lead to an increase in problems.

The effect of absence of command was set out simply in a letter dated 17 April 1920 from Staff Sergeant Percy Gray (AGS) to the Returned Soldiers Association – ‘We are living practically as civilians over here’. Spedding asserted to the COI that the men on appointment were clear that they ‘were working under active service conditions’. On the ground, neither Kingston or Lee would enforce this. Thus, the wives of some men were allowed to stay with them in the Villers-Bretonneux hutment, even though the huts ‘were poorly constructed and badly ventilated and totally unfit for housing’. The wives drank in the sergeant’s mess where the officers fraternised with the NCOs ‘on an equality’.

Immorality

The issue of immorality exercised the Court of Inquiry. ‘Women of ill-repute were notoriously and openly occupying huts with the men’. Sergeant Carr agreed that ‘women have been in the camp for immoral purposes’ but begged that ‘I was not aware that immorality was a military crime’. The delightfully self-titled ‘respectable mothers’ of Villers-Bretonneux had written on 19 March 1920 (albeit at the instigation of Lee) in complaint about Kingston who ‘has not been trying to make things better’. They claimed that there had been a fire at the AGS hutment and ‘about 10 girls or women came out … half-dressed, some were nearly quite naked’. Several British WAACs were also noted as occasionally present. (The COI was particularly interested in cases of sexually transmitted disease and may have been disappointed to learn that only three were reported, although Sergeant Carr described administering ‘wash-outs’ of argyrol, an anti-infective used on a preventative basis).

This immorality was not restricted to privates and NCOs. Lieutenant Lee ‘behaved himself in a scandalous manner’ living openly ‘with a woman of notorious character as his wife’ (the rather curiously named ‘Legion’). Lee was, of course, awaiting the arrival in France of his actual wife. He was asked at the Court of Inquiry if the relationship with Legion ‘was a condition necessary to a man’s life?’ and replied ‘Yes, I have always done the same’. Even Spedding was forced at the end of his evidence to acknowledge that he had lived with a woman in France, unknown to other military personnel, protesting that ‘I paid them nothing’. His cross-examiner asked: ‘But you knew you committed a military crime?’, and Spedding replied: ‘Yes, I know I committed a military crime which is condoned’.

Drunkenness

Drunkenness ‘was a common and frequent occurrence … and no disciplinary action was taken to check it’. On one occasion drunk men ‘wantonly discharged many shots from a revolver’. Kingston, who allegedly encouraged his men to call him ‘Charlie the Bastard’, was no less a participant, his place of choice (Victor’s Café) becoming known as ‘Kingston’s Retreat’ or ‘Captain Charlie’s Boozer’, where he perfected the ‘Villers-Bretonneux Cocktail’, a nauseating blend of whisky, rum and sauce, served in half-pint mugs.[17] Driver Willoughby Richard Bollen (who had represented complaints direct to Australia House) testified to the court that Kingston ‘was drunk perhaps two or three times a week.’ Further, adding to the vision of an officer unable to maintain the necessary boundaries, he asserted that in Kingston’s favourite estaminet, ‘he acted generally as flunkey to all’. He continued that ‘drinking was going on in the camp at all times … sergeants were permitted to feast at all times day and night’. Bollen is described as a ‘growler’, and was unpopular, particularly for fraternising with (and allowing his wife and sister to fraternise with) the attached German prisoners. It was Kingston’s failure to deal with his complaints locally that prompted the complaints to London. In terms of Bollen’s statements to the inquiry, however, they are broadly supported by the testimony of others.

In Amiens, Lee’s staff were actively engaged in running two estaminet/brothels, this with a financial interest therein. Sergeant Athol George Coughlan apparently paid 17,000 francs for a share of one such enterprise, which he ran with the woman he lived with, ‘Maltese Molly’, an older prostitute, for whom he pimped. (Coughlan was at one point held at gunpoint and assaulted by another Australian, her former lover). The soldiers would work in the estaminets in uniform. Lee gave ‘evasive’ answers to the court in relation to his (clearly certain) knowledge of this

Misuse of transport

The section transport was used to ferry privates and NCOs to a brothel in Amiens, notably the ‘Red Light Depot’, the car waiting to collect them after their exertions. Kingston, incapable of setting an example, freely admitted to the court that ‘I have been the one great joy-rider in the Section’.

Theft

Transport, under Kingston’s command, was targeted for theft. Extraordinarily, the Quartermaster Sergeant at Villers-Bretonneux entered into negotiations for the sale of an ambulance for 18,000 francs ‘with the understanding that the car was to be represented as lost, and the proceeds divided among two members of the AIF’. The witness at the COI, Corporal Thomas William McKay, implied that this was a known practice, a syndicate covering France, Belgium and Germany involving a ‘ship’s captain’ and an English and a Scottish officer. Driver Gordon Wallace Furphy described how: ‘The papers were made up and the cars were put on the ship and landed in England without anyone knowing anything about it’ – in France the vehicle would be reported as stolen. Mckay was originally approached in Rouen by a Frenchman posing as English, but the one man he identified from the syndicate was ‘Captain B W George DSO’. Mckay described him as in uniform with ‘badges on that looked like the RAMC uniform’. This appears to be Benjamin William George DSO who was a Lieutenant in the Royal Naval Reserve and Captain in the Mercantile Marine. [18] His DSO had been awarded as a result of a successful 4-hour engagement with a submarine in July 1917. He had been demobilised in February 1919, and retired in June 1920. Clearly the ‘ship’s captain’, if the criminally-minded Mckay remembered correctly, he was seemingly masquerading as an army officer. George offered to take Mackay to see the ship in the Rouen docks. An Assistant Provost Marshal was also involved, who would only begin looking for the ‘stolen’ car a week later. There is no indication that George’s activity was ever discovered by British authorities – in 1922 he was awarded the Gold Medal of the Shipping Federation. Car parts were equally sought after – the French imposter attempted to secure 50 tyres from the supply depot to sell on. The Medical Officer had parts of his car stolen and sold. More generally, petrol was drawn on the section and sold on. Mackay, who had always served in Motor Transport observed that ‘I have met with a great deal of roguery in the MT units’.

On another occasion Kingston’s section reported an ambulance stolen coming from Calais loaded with supplies. His men ‘found’ it burnt out in a field, the supplies ending up in the hands of locals in Villers Bretonneux. Similarly, Red Cross rations parcels, cigarettes and clothing were sold to both British and French personnel, even thousands of rolls of film intended for grave photography. Kingston’s lax approach to record keeping made such thefts easy (he kept, for instance, no record of leave and signed blank passes and order forms left with an NCO for distribution).

All of these nefarious activities happened on the watch of Charlie Kingston. Flawed as an individual like Lee, albeit in different ways, Kingston was a man who had shown himself courageous in war. Matt Smith entitles his chapter on him in Cahir’s book ‘A Credible Officer Befallen by Circumstance?’, offering a range of explanations for his behaviour: ‘Whether through the stress of war, monotony of the graves services work or a general desire to aspire to greater things, or perhaps a young man led astray’. Smith concludes that the evidence of the COI ‘suggests the Kingston’s capacity to carry out his duty was hampered by war-weariness, alcoholism, and apathy’. There is no evidence for any of this. In fact, the court concluded that Kingston was simply ‘wholly unqualified and unfit for command’. He had spent his war career as a private and NCO, i.e. a man in receipt of officers’ orders. In this position he did his duty. His rapid promotion did not make him a ‘credible officer’, as he clearly did not have the capacity to issue orders, see that they were carried out, or grasp the necessary distance between officers and men that these duties required. Never having truly lost his NCO identify, he simply curried favour with his men, used as he was to their company. What allowed this to take hold was the vacuum within which he operated, with little or no oversight from a senior officer. This was, above all, as with William Lee, an organisational failing that facilitated a personal failing.

(d) The quality of the ‘sacred duty’

The COI determined that ‘this effort to honour the dead shall only be the means of bringing shame and disgrace upon the good name, fame and reputation of Australia.’ Lieutenant Lee stated in his evidence to the court that there were ‘many error’ on the wooden crosses in the cemeteries, involving names and years killed. He blamed this on the fact that ‘Captain Kingston did not supervise the work in the field’. This was clearly not all Kingston’s fault as Warrant Officer Thomas Harley described a cemetery with 500 Australian burials where there were 300 crosses to be renovated due to errors which clearly emanated from the hospital or Casualty Clearing Stations where the individual had died. Similarly he reported enquiries from Australia about men who were recorded as having ‘two or three graves’. Visting the Villers Bretonneux Cemetery, however, Lee complained that he could find the Memorial Cross team on only one occasion – ‘they were always in the shops’. Not only were the memorials in ‘very bad order’, he ‘gave instances of crosses being taken up from the correct graves and being put over wrong graves’ by Kingston’s men. He alleged crosses were painted over thus causing confusion – at Roisel he claimed Australian 19th Battalion crosses were painted over and attributed to men from 191st Labour Company (no men from these units lie in the cemetery currently, however). The work had been ‘carelessly, negligently, and inefficiently done’.

Sergeant Coughlan (brothel owner, pimp, and printer in civilian life) had been appointed as a surveyor/draughtsman in relation to the cemeteries. He told the court that in relation to survey work: ‘I do not know too much about it’; and in respect of the tasks of a draughtsman: ‘I had little experience’. Photographic duties were a crucial part of the work and Spedding told the court that of the 11 photographers possibly only seven had previous experience of this work, and reported that Lee had told him the photographers were idle. Often only four photographs were achieved per day, and from 13 December 1919 to 27 January 1920 no photographs at all were taken, bad weather and poor light (which inexperienced photographers did not know how to compensate for) and lack of transport cited as the problems. The photos were not processed in France (due to issues of supply of water and chemicals), the ‘photographic expert’ being in London. Men had therefore no feedback on their work and a number of photos were duds, graves often having to be re-photographed. Examples of composition errors included ‘a Chinese behind a tomb’ and ‘a German prisoner sleeping near a post’. Each photo cost £57 in current values.

The second Court of Inquiry

The second Court of Inquiry (28-31 December 1920) was a much more focussed affair involving very specific allegations against Phillips and Allen. It came about as a result of the continued complaints (described as ‘long and rambling’) of Lee in Australia, directed to the Prime Minister and the senator for Western Australia, Sir George Foster Pearce. There were already rumblings in the Australian Press over the poor state of affairs in France, one William Babington Dynes (late lance-corporal in an Australian Tunnelling Company, and married to a French woman) describing the AGS in the Sydney Morning Herald as ‘an organisation consisting of spare parts, in which inefficiency, bungle and waste were the leading rods’.[19]

Lee alleged that Allen had ‘large interests in patents apparently in England’, and had come to Europe to further these interests, and took time away from the AGS to attend to these. He claimed he had been dismissed as a result of ‘conspiracy’ between Phillips and Allen who had ‘influenced’ the court in the first COI (promising two of the panel members, including Meikle, jobs in the AGS – not necessarily a realistic inducement). He further accused Phillips of using an AIF driver and car for personal purposes. A new complainant was Lieutenant Samuel Thomas Macmillan, a 42 year-old journalist, whose war had been spent in the records section at AIF HQ in England and who had been commissioned in June 1919 and placed in charge of the Graves Registration Branch in London from July 1919 and attached to the AGS from March to July 1920. He was clearly acting in collaboration with Lee, and accused Allen of an attempted hoax concerning the location of the burial of Lieutenant Robert David Burns (killed in action at Fromelles on 20 July 1916 serving with 14th Australian Machine Gun Company). Macmillan (who believed that he should have been appointed CO after Spedding was despatched, and who referred to Phillips as a ‘crawling bastard’) himself was not spotlessly clean – he had apparently forged another officer’s signature for receipt of money (over £60) from several families for ensuring a gravestone and inscription; and a similar forgery, receiving money for the removal of another deceased soldier. He had been sent back to Australia for ‘unsatisfactory’ service.[20] All the complainants had had their service terminated and might be thought of as having axes to grind.

A disarming hagiography exists in the National Archives of Australia concerning Alfred Allen, written by John Oxenham (William Arthur Dunkerley, an English journalist, novelist, hymn-writer and poet).[21] He describes: ‘A plumb square man … a Quaker, a non-drinker, non-swearer, a born leader of men, with a most remarkable memory, and intuitive perception of possibilities, and mind trained to minute observation and deduction, no finer man could have been chosen for the arduous post he fills’, possessing the ‘loftiest sense of duty’. The ‘discoverer of missing men’, he described, ‘carries with him a specially-made slender steel rod with an oblong slot in its sharp point, and with it he delicately probes the soil in all likely spots …. and in a manner little short of magical the earth yields up its secrets to him”. Oxenham concluded: ‘A good man, a great man, a man worth knowing’. Mrs Allen might not have agreed with the ‘plumb square’ epithet. Her Sydney architect husband abandoned her (and his 14 year-old daughter) in 1914 for Europe and never saw them again. Nor was a ‘magical’ ability to locate Australian dead reflected in the case of Lieutenant Burns, or the Pheasant Wood burial pits, as will be seen. The ‘loftiest sense of duty’ would be little on display. Oxenham claimed that Allen was finding 70-100 men per week in areas already cleared. This claim is fantastical – in his time with the AGS, Allen would have found some 7,000 bodies at this rate. His ‘divining rod’ was no such thing – others used such a tool, sniffing the tip after probing to smell for putrefaction.

The Quakers had sponsored Allen’s work with the Red Cross in the Netherlands where he worked with Belgian refugees; and from 1917, in London. His employment with the Graves Service, as an architect, was initially focussed on monuments, the delivery of which he was unimpressed with but could do little about, due to the contracts with local builders. Spedding was irritated by his assertion of the rank of major, and stated that Allen knew nothing of the AIF or the military (a repeated claim at the first COI), did not know the geography of France and could not read a military map. Lee viewed him as a ‘disguised civilian’. Sergeant Gray would use identical words writing to the Returned Soldiers Association that Allen was merely a ‘camouflaged civilian’, and his authority over soldiers was ‘a sort of joke amongst the Imperial officers’.

Whilst the accusations against Major Phillips and his use of both driver and car were dismissed, (as were allegations that he had attempted to influence the panel of the first COI), Phillips was also implicated in the charge against Allen of the grave hoax. Lieutenant Burns’s father was Colonel James Burns who had commanded the Australian 1st Light Horse Brigade until 1908. He had contacted Spedding concerning his son’s grave location. Hearing nothing, one Cecil Smith, who was married to James Burns’s niece, and who was also the London representative of Burns’s shipping company (Burns, Phelps & Co) was asked by the family to pursue the matter.

Spedding wrote to Allen on 8 September 1919 concerning the location of Burns’s burial. The letter also stated that: ‘A communication from Germany states that there are five large British Collective Graves before Pheasants Wood near Fromelles and another (No. 1 M4.3.) in the British Cemetery at Fournes. Burials were effected in these graves by the Germans after the Fromelles action and it is thought that probably Lt. Burns body may have been interred in one of these graves’. Allen was asked to ensure ‘a search be made when you are operating in this area’. This letter was sent again on 16 January 1920, London having heard nothing from Allen. On 21 February Allen replied that ‘up to the present we cannot get a satisfactory statement from GRU or DGR(E) etc. re the removal of collective graves’. He stated that he had ‘called at GRU Beaucamps (OC in charge of this area) and left all particulars which are being investigated’. Allen stated that he knew about the ‘massengrab’ at Fournes, which was marked, ‘but up to the present no information can be given as to who is buried there’. On 4 March he wrote again that ‘after another search and investigation the cross’ (i.e. over the ‘massengrab’ at Fournes) ‘is, in my opinion the Cross and Grave asked for’ and suggested ‘acceptance that Lieut. Burns is buried with others in this grave’. At the COI he retracted this certainty, merely saying the he thought it ‘might’ give the location of Burns. He had, of course, absolutely no evidence on which to base this. He added that ‘the cross and grave were originally placed by the Germans at a spot near Fromelles and Pheasant Wood and since collected by them and replaced in the cemetery’. This claim appears entirely illogical – why would the Germans have exhumed graves to move the bodies to a mass grave? Macmillan signed a letter on 28 April instructing Allen to have the Fournes grave opened, which Allen requested (4 May) the Department of Graves Registration and Enquiry (DGRE) to expedite. It is clear from the correspondence that Allen had done little more than ask the British to pursue the issue.

The proceeding was given impetus by the terrier-like Cecil Smith. He had attended Australia House during Phillips’s first visit to France and had been told that he could be present at the exhumation. When Phillips returned and discovered this, he wrote to Smith saying that his presence was not permissible under the British rules. Smith then approached Sergeant Michael Skelton, one of Allen’s NCOs, asking to be informed about the exhumation date so he could be on the spot by ‘accident’. Phillips expressed his irritation about this face-to-face with Smith and reaffirmed the advice that he could not attend (12 April). Smith, who found him ‘very nasty’, immediately went over Phillips’s head to Lieutenant-Colonel George Justice Hogben, assistant secretary to the Australian High Commissioner, who gave permission. Piqued, Phillips wrote privately to Allen stating that Smith had acted ‘unwisely’, that he ‘did not wish’ Smith ‘to see the exhumation’, encouraging Allen to have the exhumation done before Smith could arrive. Allen allegedly never received this, and Phillips cancelled this message the next day by wire. The dictated letter disappeared, removed by Macmillan. It is clear, however, that Phillips intended no hoax – he was simply irritated that his authority had been usurped by a civilian, and was determined to be obstructive, immediately relenting.

Phillips wrote to Meikle to inform him that Smith had now been given permission to attend the exhumation at Fournes and asking to be given a date so that Smith could travel to France. This was forwarded to Allen on 17 May. The previous day Allen was allegedly ill, although well enough to travel to Ypres to be told he was required at an important meeting and would have to cancel the Fournes exhumation which had been arranged for the 18th. (The officer in question, Colonel Sutton, Commandant No. 5 District, could remember little of this when questioned by the court, except that Allen did not attend the meeting). Smith was already in Belgium, and visited Allen on the morning of the 17th, who informed him that he still had not received permission for Smith to attend. Allen then took himself to hospital with ‘typhus fever’, saying he would rearrange the exhumation for the 20th. He remained in hospital, according to his officer file until 31 May, this clearly being incorrect as he was writing letters from Bird Cage Camp, Poperinghe, on the 25th). Smith turned up at Fournes on the 18th, to find the British present but no Australians, and was told he could not be present. He attended again on the 20th, now with permission, but to his disappointment – the grave was opened to a depth of 8.5 feet and ‘no trace of any bodies could be found’. Exhumation of the adjacent grave No.1, marked ‘Englander’, revealed five bodies, all British – ‘no trace of anything Australian could be found’.

On 19 June Allen wrote a long report on the matter. In this he claimed that ‘I carried out a personal search, walking many miles in various areas, trying to locate the reported Isolated Collective Grave, supposed to hold Lieut. Burns, near Fromelles’. At the COI he would further claim that prior to the matter of Burns being raised ‘I made an exhaustive search all round Fromelles, Pheasant Wood and a portion of Fournes’. (This is not true as Allen advised Phillips on 24 January 1920 that ‘it had not been possible to arrange a search up to that date’). He continued in his report that ‘a little cemetery on the other side of Fromelles was found and from this the bodies had been removed’. At the COI he elaborated this further: ‘I traced where a cross had been removed, the inscription giving the exact date of death, and was informed a British Officer had been “lifted” by the Germans and removed but no one knew where’. As noted above, the likelihood of such an act seems miniscule. Allen claimed that this intelligence was from locals, but as is known, civilians had been removed from the vicinity of the front lines. At the COI he enlarged that ‘I located this cross in Fournes cemetery, the only cross of its kind with the date of death and the word ‘Fromelles’ on the cross’. This claim is bizarre as Allen had been informed exactly about the Fournes mass grave nine months previously, and had to ‘find’ neither cemetery or cross.

Conclusions

Firstly, the AGS was revealed by the first COI as a shambles of immorality, drunkenness and minor criminality. In this it assumed and expanded upon the allegedly disreputable mantle of its predecessor, the AGD. This was, of course, simply a development of the lack of discipline inherent in the AIF in the decompressed post-Armistice environment. John Mott clearly had authority enough to hold discipline together as best he could within the AGD. The absence of any proper organisational structure within the AGS, supposedly managed as it was from London, led to the collapse of local officer authority and willingness to enforce discipline, and allowed personal flaws to run riot in a race towards the moral bottom. To what extent similar malpractices existed in the British forces is unknown but the existence of a ring of British officers stealing army cars and shipping them to Britain seems a far more serious matter, and one that went, seemingly, ignored and unpunished.

Secondly, did Alfred Allen attempt to hoax Mr Smith on behalf to the Burns family? The court concluded not. The explanation is likely much more banal. A number of senior witnesses at the second COI testified that Allen was doing a good job. Yet there is good evidence from the records of the inquiry that he did not tell the truth. He stated that he had searched all the relevant areas before he heard of the Burns case, which he did in September 1919. Yet he was only appointed on 21 August that year, when he was preoccupied with memorials, and the following January stated that no search had been carried out. His claim of walking miles and finding nothing is clearly hollow – his correspondence with London indicates that he simply sought information from the local Graves Registration Unit. Indeed, whilst his inspection role included ensuring that Australians were correctly identified, search was never part of his job, nor was it part of the task of the Australian Graves Service. Even when Hogben summarised the future work of the AGS on 8 July 1920, any search for ‘isolated AIF graves’ was to be conducted with DGRE (i.e. a reiteration of the inspection role) unless they had been reported by independent sources (DGRE still having to carry out the exhumation). Allen had only five photographers on hand to spring 1920, and in July had 10 staff (likely including memorial personnel), hardly enough for search parties when they had other duties. One man on foot would literally have been looking for a needle in a haystack when DGRE reported that even in 1921 in that locale ‘there was many surface indication (sic) of very heavy death-toll and traces everywhere of bodies blown to pieces’.[22] Those who have taken the Oxenham text as gospel, this emerging in the Australian newspapers in early 1920, have been mislead. If Allen was the magical corpse diviner, how could he have failed to find the Pheasant Wood mass burial pits in which Burns would be located decades later? Allen had simply made a guess as to where Burns was, and when he realised that this was to be put to the test, disappeared into hospital. Far from a hoax, what happened simply reflected Allen’s organisational limitations and personal inadequacies.

Allen was the third of the key AGS officers to reveal his personal flaws. He was clearly a vain man (who no doubt revelled in Oxenham’s hagiography), who was at times unfamiliar with the truth – Van Velzen notes how he repeatedly lied about his age and height on official documents. He spun a story of being ‘gassed’ in a London air-raid.[23] His misrepresentations to the COI are clear. A successful architect, he fantasised about becoming a missionary. Likely reacting to his son’s abandonment of wife and child (whom he never subsequently mentioned to anyone), Allen’s father left nothing to him when he died in 1917. Allen was one of five Australians (along with Meikle and Phillips) who went on to work for the Imperial War Graves Commission in 1921 and 1922 after the Army hand over the exhumation work to them. He subsequently emigrated to Africa and farmed for nearly 10 years, returning to the UK to work once more for the Quakers. He died of throat cancer in 1936.

Thirdly, this is not an article about Pheasant Wood, but Allen and his fellow Australians’ role in failing to find the mass graves deserves comment, as confusion abounds about this. Peter Barton, central to the final location of the mass graves, speculates about this failure in his exhaustive study of Fromelles. As he notes, ‘the units that exhumed and reburied Allied dead in the Fromelles sector were British: the 6th, 8th, 48th and 84th Labour Companies working alongside Nos. 27 and 33 Graves Registration Units’. [24] He goes on to quote a reply from Phillips to Charles Bean, the Australian historian, in 1927 referring to a British report noting that Pheasant Wood was ‘in the area covered by the Australian Graves Department in their search for isolated graves’. It was noted the associated reburials were in VC Corner Cemetery. There was of course no Australian Graves Department, but if it was the AGD that was being referred to, their war diary listing locations searched indicates they worked purely on the Somme and did not bury at VC Corner. Phillips added that ‘this is correct as this work was carried out under my personal instructions’.[25] Phillips, of course, was not connected to the AGD, so these instructions must therefore refer to the AGS and presumably to his instruction to Allen in respect of tracing Burns’s burial. Nigel Steel goes on to assert on the basis of this that ‘these documents confirmed that the AGS did carry out meticulous searches of the Fromelles area’. As is clear, the AGS did not have either the brief or manpower to do any such thing. He goes on to suggest, based on the listed map locations from which reburials were made: ‘Maybe … the AGS looked in the wood for graves but not behind it’. Alfred Allen, as he disclosed to the first COI, could not read a military map, but knew the graves were ‘before’ the wood and not in it. As is known, the three open and unused burial pits were located by aerial reconnaissance, and although the photographs would not have been available, the three pits appear on British trench maps in 1918. Barton suggests that it is likely they would have remained open post-war. He lists five possibilities in relation to Allen’s failure: ‘(a) He made no exploration of the ground at all; (b) the exploration was incomplete; (c) it was carried out in the wrong place; (d) the graves were overlooked; and (e) the graves were deliberately ignored.’ The evidence considered here suggests that he made no exploration – such a man would never have ignored the graves and the chance to be a true Australian hero.

As this writer has observed, the recovery of the dead was a grim task carried out by unsentimental men, often in wasteland conditions and foul weather and not always with due care and attention – we only have to look at the War Office inquiry into the work of 68 Labour Company at Hooge Crater Cemetery to realise this.[26] It was no ‘sacred task’. At best, even if covering his own inaction, Allen could be construed as attempting to give Lieutenant Burns a home in death. He would not be the first. The attempts of Major Arthur Lees (in charge of GRUs at Gallipoli), to achieve identification are clear in his letters. In August 1919 he wrote asking for an exact description of a Grenadier Guards button. ‘We have found a button on an officer with a crown on top G.R. and G.R. reversed and then a grenade; if it is Grenadier Guards it is Col Quilter, but no one can identify the button.’ (John Arnold Cuthbert Quilter was the CO of Hood Battalion, Royal Naval Division, killed on 6 May 1915). Two months later he wrote again: ‘Not absolutely certain about Col. Quilter’s grave. He is buried in rather a mysterious little cemetery where there are 10 candidates for five graves but if I can’t find him elsewhere I will give him a home.’[27] The insinuation is that Lees would manufacture an identification.

Captain Meikle of the AGS would address this issue publicly. It was reported in the Daily Herald, Adelaide, on 3 January 1921, that Meikle, observing that ‘the majority of those reported missing are practically identifiable owing to the places and circumstances’ in which they were found, but that ‘the strict rule hitherto’ had been that a memorial should not bear a name ‘unless identification is positive’. The article continued: ‘It is suggested by Captain Meikle that it is better to take the chance of an occasional mistake than to leave many thousands of bodies unnamed and unknown’. Meikle apparently believed that it did not truly matter if a family travelled from Australia to the Western Front to weep at a graveside which did not actually contain the body of their loved one, as long as they believed it did. Was this a kind deception? We cannot say that he was wrong.

Endnotes

[1] P.E. Hodgkinson, ‘Clearing the Dead’, Journal of the Centre for First World War Studies, 3, (2007). Available at: http://www.vlib.us/wwi/resources/clearingthedead.html.

[2] National Archives of Australia (NAA): MP376/1, 446/10/1840. Court of Inquiry to inquire into and report upon certain matters in connection with the Australian Graves Service. (All further quotes which are not footnoted are taken from this document).

[3] F. Cahir et al, Australian War Graves Workers and World War One, (Singapore: Palgrave Pivot, 2019).

[4] M. Van Velzen, Missing in Action, (New South Wales: Allen & Unwin, 2018).

[5] Australian War Memorial (AWM), 2018.8.765 Diary of Australian War Graves Detachment.

[6] NAA: B2455, Mott, John Eldred.

[7] J.P. McKinney, Crucible, (Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1935), p.200.

[8] C. Corns and J. Hughes-Wilson, Blindfold and Alone, (London: Cassell, 2001), pp. 390-1.

[9] C. Rhoden, ‘Another Perspective on Australian Discipline in the Great War: The Egalitarian Bargain’, War in History, 19, (2012), p.448.

[10] Rhoden, p.446.

[11] N. Wise, ‘”In military parlance I suppose we were mutineers”: Industrial Relations in the Australian Imperial Force During World War 1’, Labour History, (2011), pp.161-176.

[12] J. Smart, ‘”A sacred duty”: locating and creating Australian graves in the aftermath of the First World War’, (AWM Summer Scholars, 2016), p.8.

[13] NAA: A471 11376, Court-martial Pte Alexander Simula.

[14] NAA: A457 W404/7, Cable 28/09/2021.

[15] Spedding returned to journalism. He became honorary publicity officer of the Returned Sailors' and Soldiers' Imperial League of Australia in the 1920s and 1930s, and compiler and editor of its Official Year Book from 1933. In 1946 he became press secretary to the New South Wales premier (Sir) William McKell and his successors. He died in 1974.

[16] NAA: B2455, Phillips, George Lort.

[17] https://onehundredstories.anu.edu.au/

[18] The National Archives ADM-240-83-228 & ADM-340-54-24 B W George.

[19] Sydney Morning Herald, 7 February 1920, cited in Van Velzen.

[20] NAA: B2455, Macmillan, Samuel Thomas.

[21] NAA: A458, R337/7, item 87607. Graves. Visit of Mr Bruce.

[22] N. Steel, ‘’Another Brick in the wall’, Australian War Memorial, Wartime Magazine Issue 44, (2012).

[23] Van Velzen, Kindle Edition locations 2657 to 2691.

[24] P. Barton, The Lost Legions of Fromelles, (London: Constable, 2014), Kindle Edition location 6151.

[25] Barton, location 6324.

[26] Commonwealth War Graves Commission, CWGC/1/1/7/B/48, Report of Committee of Enquiry into Hooge Crater Exhumations.

[27] Imperial War Museum Documents 1068. Private papers, A.C.L.D. Lees. (Quilter is buried in Skew Bridge Cemetery, one of 257 casualties).

Becoming a member of The Western Front Association (WFA) offers a wealth of resources and opportunities for those passionate about the history of the First World War. Here's just three of the benefits we offer:

This magazine provides updates on WW1 related news, WFA activities and events.

Access online tours of significant WWI sites, providing immense learning experience.

Listen to over 300 episodes of the "Mentioned in Dispatches" podcast.