Killed by Treachery

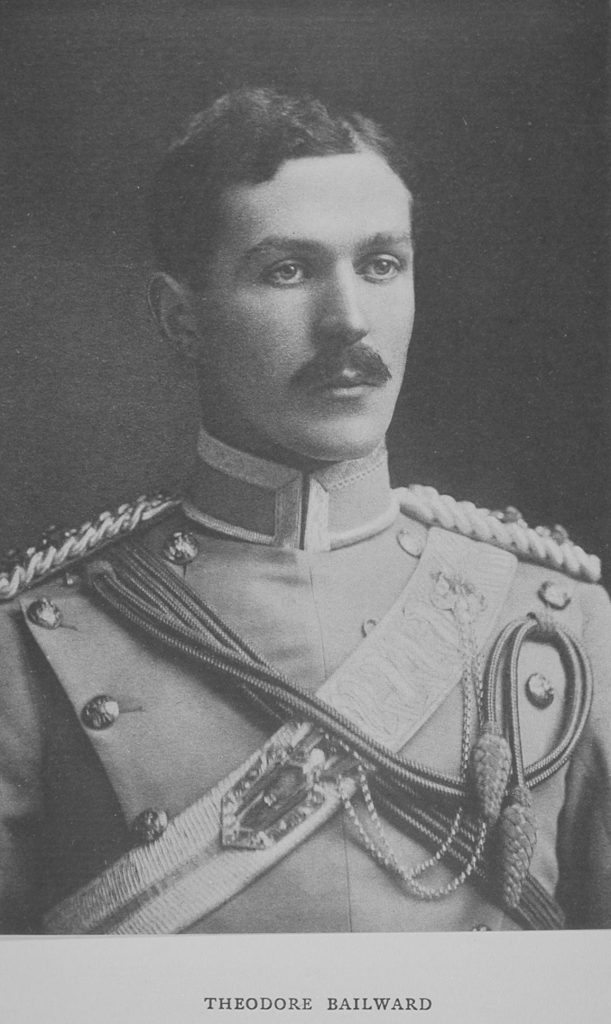

Whilst working on an index that was being created for the two volumes of ‘The Bond of Sacrifice’, one of the WFA’s volunteers noticed an interesting line that had been inserted into an officer’s obituary. This obituary, for Lt Theodore Bailward of the 26th King George’s Own Light Cavalry (a regiment of the Indian Army), stated he had been ‘Killed by Treachery’ on 29 April 1915. I thought this was worth further investigation.

A quick search on the CWGC database revealed that Lt Bailward was killed on the day stated and is commemorated on the Basra Memorial to the Missing in present-day Iraq. He was the “Son of Thomas Henry Methuen Bailward and Margaret Eliza Bailward, of Dorsington Manor, Somerset.” This address as recorded by the War Graves Commission is not totally accurate, as Census records show the family seat was in fact Horsington Manor, near Templecombe in Somerset. The Bailwards were a very wealthy family, having eight servants in 1901 and ten servants in 1911.

Theodore Bailward was clearly a fatality of the Mesopotamia campaign; it can be seen from the CWGC that he was attached to the 7th Hariana Lancers and was one of two men commemorated from this unit who died on this day named on the Basra Memorial; the other man being Assistant Armourer Abdul Ghani Khan, who was the “Son of Nawab Ali Khan, of Kahnawr, Rohtak, Punjab.”

An inspection of the Official History of the Mesopotamian campaign, published in 1923,[1] reveals more details about the action, recounting how a “Major Anderson” and two British officers were killed “thus falling victims to Arab treachery”. But there is an added complication: the official history reports that three British officers were killed on 29 April 1915, but on inspecting the list of fatalities from the CWGC for those commemorated in Iraq there was no one by the name of ‘Anderson’, nor any other British officers killed other than Bailward. This was a puzzle. The Official History did tell us, however, that Major Anderson was from the 33rd Cavalry, which – going back to the CWGC database of men killed on this day and commemorated in Iraq – gave three other names of ‘other ranks’ who were killed presumably in this action. These were Lance Daffadar (the rank is equivalent to a Corporal) Ramdatt, and Sowars Jaigram and Ramrichhpal.[2] As with Lt Bailward, they are commemorated on the Basra Memorial.

Clearly another approach was needed. Turning to a digital copy of de Ruvigny’s Roll of Honour (a similar work to Bond of Sacrifice, although generally less detailed but with many more names listed) a much fuller entry for Theodore Bailward was discovered in volume 1. This added further biographical information and again confirmed he was killed with two (unnamed) officers and some men at Imanzadeh Ali Ibuhussin, 18 miles due east of Ahwaz. But the obituary did not resolve the mystery of identity of ‘Major Anderson’ or the other officer.

Increasingly perplexed, and turning to Google and focusing on the name of ‘Bailward’ and ‘de Ruvigny’ a result came up with four hits on the name Bailward – three of them from his obituary and one elsewhere in the volume, this ‘extra’ hit was for an obituary for an officer called ‘Alfred Clive Le Mesurier’.

Reading Le Mesurier’s obituary it detailed not only the name of ‘Bailward’ but also the name ‘Anderson’. So now the three officers all had names and were linked together by the entry for Le Mesurier. But still, the question remained where were they commemorated?

Putting ‘Le Mesurier’ into a CWGC search for 29 April – he came up. But the surprising aspect about this ‘answer’ was that he was commemorated on the Tehran Memorial. Obviously Tehran is not in Iraq, which was the error I’d made at the outset. I should clearly have widened the search beyond Iraq and would have found Anderson readily enough. Having at last identified Major ‘Macclesfield Heptinstall Anderson’ as the officer who had been killed in this action, it was easy to learn that had been born in 1872 and was the Son of Gen. Sir Horace Searle Anderson, K.C.B., I.S.C., Indian Army and Lady Anderson (nee Woods), of Seercroft, Faygate, West Sussex.[3] Like Le Mesurier he was commemorated on the Tehran memorial.

But why were two officers (Anderson and Le Mesurier) commemorated on one memorial (Tehran, Iran) and the other officer (Bailward) on another (Basra, Iraq)? In an attempt to answer that question I delved down another ‘rabbit hole’ and investigated the Terhran Memorial in Iran. Unfortunately, whilst discovering a great deal about this memorial and about war graves in Iran, it did not answer the question as to why the commemorations of these officers were split, not just on different memorials, but in different countries!

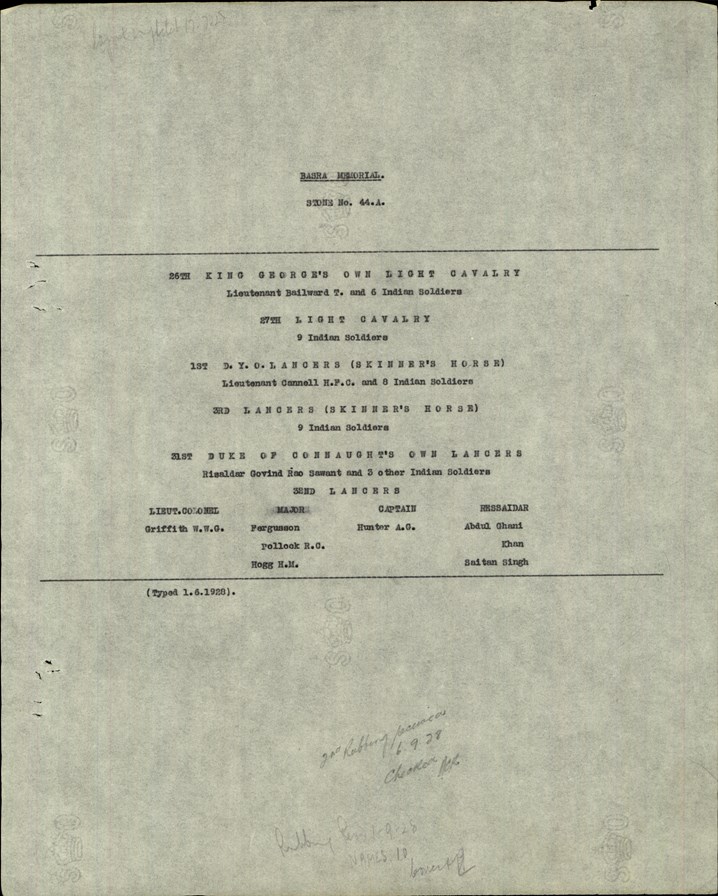

Basra Memorial

Turning to the Basra Memorial, the fact that this lists the name of Theodore Bailward is something of a mystery. As will be shown later in this article, the action occurred on the Persian side of the Persian / Mesopotamian border, but his name was inserted on the Basra memorial rather than a memorial in Iran.

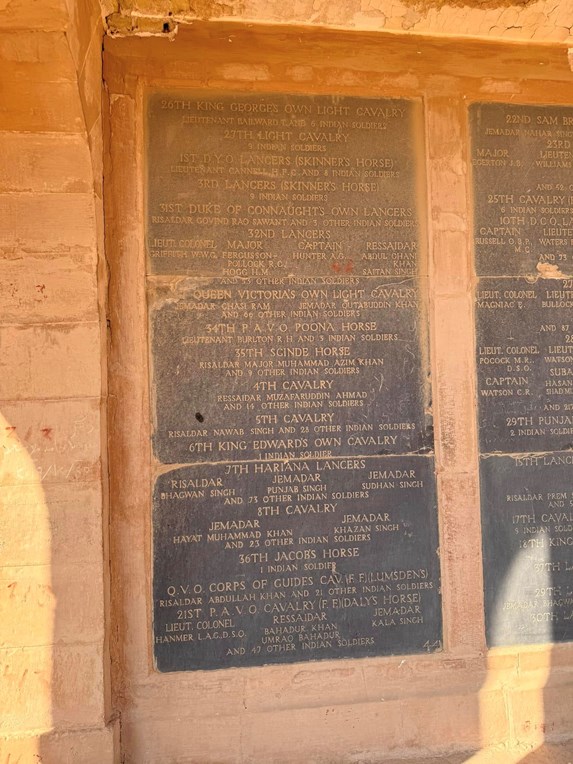

Unsurprisingly the Basra Memorial is in a bad state of repair. Following the relatively recent Gulf Wars, the difficulty and dangers of maintenance have meant that little has been possible to be done other than occasional monitoring.

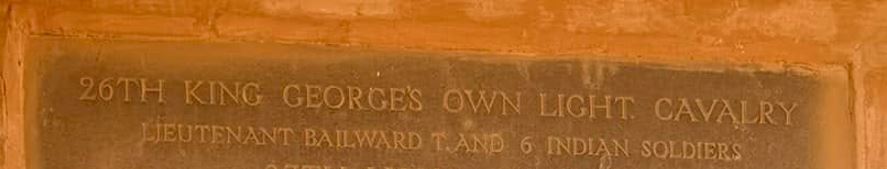

We do, however, have an image of the panel which contains the name of Theodore Bailward.

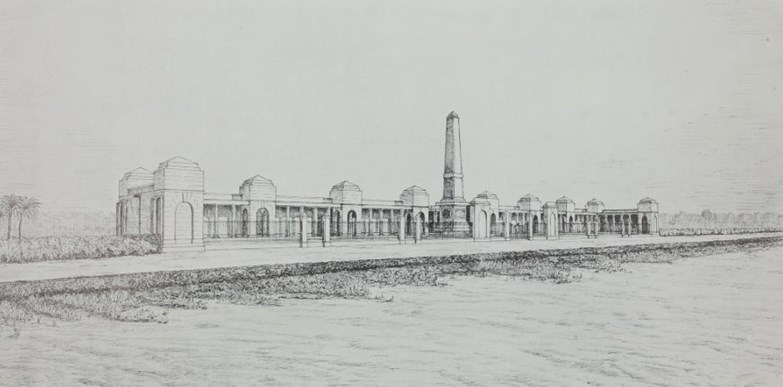

From the CWGC we learn that the Basra Memorial commemorates more than 40,500 members of the Commonwealth forces who died in the operations in Mesopotamia from the Autumn of 1914 to the end of August 1921 and whose graves are not known. The memorial was designed by Edward Warren and unveiled by Sir Gilbert Clayton on the 27 March 1929. It originally stood at the side of the Shatt al-Arab River on the edge of the city but was moved by Saddam Hussein’s regime in the late 1990s into the desert.

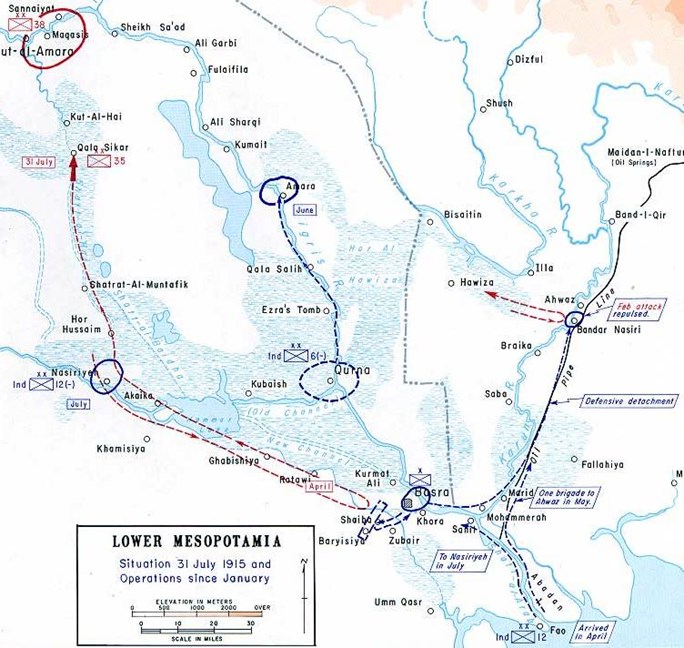

Strategic Situation in Mesopotamia in 1915

The British and Indian forces captured Basra and its vital port facilities between 5 and 21 November 1914, this established a secure British foothold in Mesopotamia and was a major step in protecting the Persian oilfields and refineries.[4]

In April 1915 the Ottomans concentrated their forces (which were a combination of Turkish troops and Arab irregulars) and launched an attack which was intended to retake Basra and – with luck – push the British out of Mesopotamia.

This attack was by way of a three pronged attempt to retake Basra. From the North they threatened Qurna on the Tigris; down the Euphrates they advanced on Shaiba and the third 'leg' was to stir up the tribes in Persia supplemented by a force of Ottoman troops.

The Turks approached the British positions around Shaiba, some seven miles southwest of Basra. The British were hampered as communications between Basra and Shaiba were tricky because seasonal floods caused the river system into a lake; as a result transport was only practical by boat. The British garrison, which numbered about 7,000 men, was attacked early on the 12th April following an artillery bombardment.

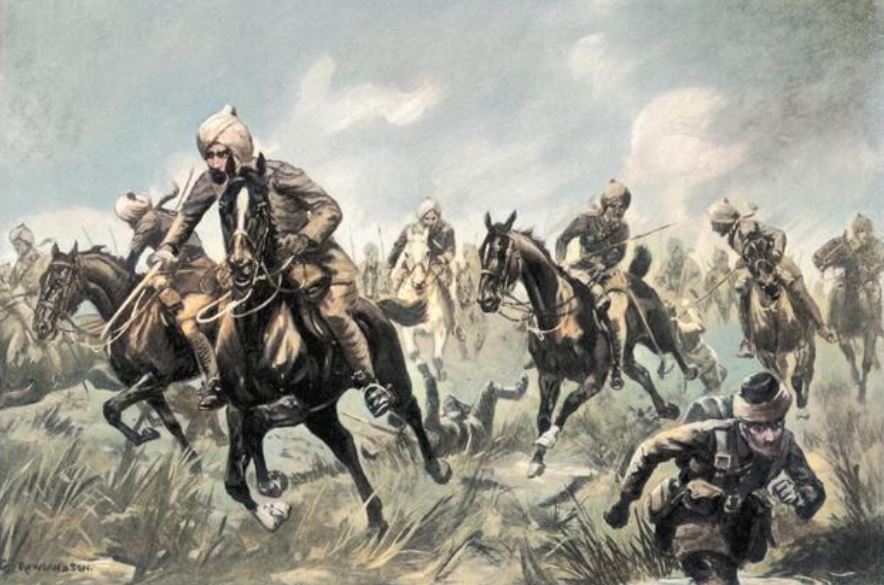

The British, commanded by General Charles Melliss, sent the 7th Hariana Lancers and later the 104th Wellesley's Rifles to attack the Ottoman forces, but these attacks were failures. Later attacks proved more successful. Ottoman troops were overwhelmed and retreated from the battlefield.

Worn out from the day's engagement, with hardly any realistic means of transportation and with their cavalry tied down elsewhere, the British could not pursue the Turkish forces. As a result of this British victory, Arab attitudes started to change: they began to distance themselves from the Ottomans, and later revolts broke out in Najaf and Karbala up river.

Having defeated the Ottoman forces, the next step was to expel the Turks from ‘Arabistan’,[5] and then to make repairs to the oil pipeline that had been damaged. To undertake this, the British had two troops of 33rd Cavalry, some artillery and an number of infantry battalions, which included one British unit (the 2nd Royal West Kents) and four Indian battalions (4th Rajputs, 44th Merwara Infantry, 90th Punjabis and the 67th Punjabis) which were based at a camp near Ahwaz (now Ahvaz). This formed part of the newly formed 12th Indian Division.

A column of troops moved out from Basra and marched 30 miles to the Karun River. Hearing of supplies being available at Ahwaz the British troops advanced towards the city despite the inhospitable conditions (the rivers were still flooded).

On 29 April, a cavalry reconnaissance was sent out to find out if there was sufficient water in an old river bed. This patrol was led by Major Anderson – he had one squadron of the 33rd Cavalry and one squadron of the 7th Hariana Lancers.

Turning back to the original intriguing line that started this line of research, it has been possible to learn about the ‘treachery’ that took place leading to the deaths of Lt Bailward, Lt Le Mesurier and Major Anderson and six others from the Cavalry patrol mentioned above.

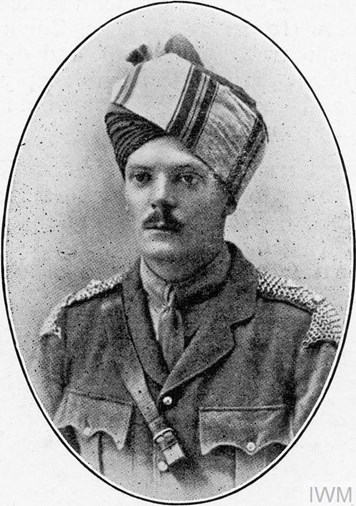

Bailward

Theodore Bailward entered Rugby School in 1901, and four years later passed on to the Royal Military College, Sandhurst. He received his Commission in 1906 in the Somerset Light Infantry, who were at the time quartered at Poona. In 1907 he transferred to the 26th Native Cavalry, a unit which was stationed at Bangalore. Six years later, in 1913, Theodore was appointed A.D.C. to the Governor of Madras. Whilst stationed in India, Theodore became a Master of the Ootacamund Hounds.[6]

At the outbreak of the First World War, and now aged 27, he was attached to the 7th Hariana Lancers.

After his death, there the following was recorded from a Native Officer of the 26th Light Cavalry:

"I have no words of energy to express my grief toward Bailward Sahib. I am exceedingly sorry to hear the death of our kind-hearted Officer. The whole Regiment, especially the ‘D' Squadron, lamented much on the loss of their beloved master. May God bless him."[7]

Le Mesurier

The Jersey Evening Post of Saturday 17 July 1915 sets out further details of the incident that led to the death of Alfred Clive Le Mesurier

“The following letter describing the circumstances in which Lieutenant A C Le Mesurier met his death has been written by a brother officer to one of Lieutenant Le Mesurier's relatives in Calcutta. Lieutenant Le Mesurier, who was formerly a member of the Assam Valley Light Horse [this formed part of Indian Volunteer Force] joined the Indian Army Reserve of Officers in November last [i.e. 1914]. The letter reads:

"My dear Mrs …. In going through your brother's papers I discovered that you were his next-of-kin in India and I am writing to tell you about the brave fellow's death and to condole with you in your bereavement. I used to know your brother at Wellington and we often used to talk over our school days together. I was not present in the action in which your brother met his death but I heard all the facts. As you know, perhaps, his Squadron Commander Major Anderson of my regiment was also killed at the same time.

“It happened like this - one Squadron of the 33rd and one of the 7th were sent out on reconnaissance some 25 miles from camp. They were met by Arabs who pretended to be friendly and warned them that the Turkish Army was only 3 hours march away and to go back. They went back about a mile and watered their horses and stayed there some time. When the Squadron had finished watering the Commander mounted the men and wheeling them about marched them off. A rear guard had been told off and your brother was sent to give them a message to keep much closer to the Squadrons. He galloped off, told the troop leader and started to come back, just as he turned hostile Arabs, who had been collecting around under the cloak of friendliness, opened fire.

“More mounted Arabs closed in and your brother was hit and fell off his horse. A native officer and three men were there but some were killed and surrounded by some 40 Arabs could not bring his body in and the remainder of the rear guard were cut up. In the meantime the remainder of the two Squadrons were being heavily infilladed and defilladed and were some 1000 yards away and so were unable to help.

“The next day a strong force of cavalry went out and recovered the bodies. Your brother was buried beside Major M H Anderson (33rd QPO Light Cavalry) and Lieutenant Bailward (26th KGO Light Cavalry) at Brackey some 30 miles from Ahwaz near the Karun River in Persia. I am sending all his personal belongings to you together with his bearer.

“I cannot say how sorry I feel over the death of your brother, my schoolmate, and I hope you will accept my condolences although they come from a perfect stranger".

Anderson

From the ‘Bond of Sacrifice’ we learn that Major Macclesfield Heptinstall Annderson, 33rd Queen Victoria’s Light Cavalry was the second son of the late General Horace Anderson, KCB and Lady Marianne Anderson (nee Heptinstall). He was born at Clifton, Bristol on 12 December 1873. Educated privately he entered the Royal Military College, Sandhurst as a King’s Cadet in 1892. Originally attached to the 2nd Durham Light Infantry in April 1895 he was posted to the 33rd Cavalry, Indian Staff Corps. As a Lieutenant he was active service in the Tirah Campaign of 1897-98. During 1898 and in 1901 he was on ‘plague duty’ in Bombay between which he’d served with his regiment in China. Promoted to Captain in January 1903 he was appointed as the regiment’s adjutant and then as adjutant to the Calcutta Light Horse. A keen sportsman, he was fond of pig-sticking, polo and shooting.

Promoted to Major in 1912 he commanded two squadrons of the regiment in Mesopotamia in November 1914 and was present when Basra and Kurna were taken and in the Battle of Shaiba (which was the Ottoman attempt to retake Basra between 12 and 14 April 1915)

On 29 April 1915 a cavalry reconnoitering detachment under the command of Major Anderson was operating in Arabistan with orders to examine a tract of country on the bank of the Karkeh River.[8] During the course of this reconnaissance the detachment came across an Arab encampment, the Sheikh of which professed himself friendly, and gave information as to the whereabouts of the Turks. The detachment watered their horses, taking full military precautions, at a place pointed out by the Sheikh. Immediately this was done, however, the Arabs suddenly and treacherously attacked our troops. Thereupon Major Anderson ordered his main body to retire at a trot, and recalled the advanced guard and flanking patrols. As soon as the main body began to move, fire was opened by the Arabs from several directions. In the fight which ensued, the British/Indian cavalry inflicted considerable losses on the Arabs but Major Anderson was killed.

A Captain of the regiment wrote:

“Regarding the details of your brother’s death you asked for, they are as follows: He and Ram Rikh, his trumpeter, were galloping away from the Arabs towards the squadron. Your brother’s horse was hit and began to falter. Ram Rikh then asked your brother to get on his horse. This Major Anderson refused, saying there would be no chance for either of them. Almost immediately your brother was hit, and began to fall forward on his horse’s neck. Ram Rikh then tried to pull him on to his own horse; he was then hit himself, lost his reins, and his horse ran away with him into the camp. There is no doubt that your brother was killed instantaneously. Ram Rikh has, I am sorry to say, permanently lost the use of his left arm, and is shortly to be invalided out of the service. He says he has served under your brother all his service, and would much rather have been killed when he was than have lived. There is no doubt he was very devoted to him.”

Major Anderson was buried at Imamzadeh Ali-Ibuhusain.

Another officer wrote:

“I need not tell you that his death was a very great loss to his regiment – all the officers and men of which were devoted to him – and to the brigade. Although I had not known him for more than a few weeks, I felt that in him I had lost one of the best and most reliable and gallant officers in the brigade…. Your brother died, as he lived, gallantly….He could, by galloping back to the main body, almost certainly have saved his life: but this would have been to desert his officers and the read guard. As was his nature, he chose the braver course. We afterwards buried him. He was killed, I hope, instantaneously and painlessly by bullet wounds. He lies buried some twenty-five miles south-west of Ahwaz, on the Karun River.”

Major Macclesfield Anderson was mentioned in General Sir AA Barrett’s despatches as specially brought to notice for gallantry in the field.

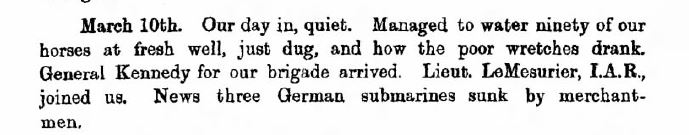

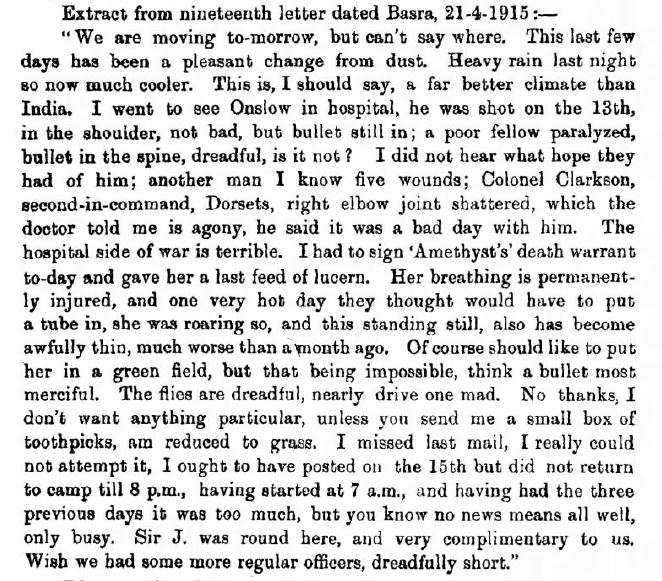

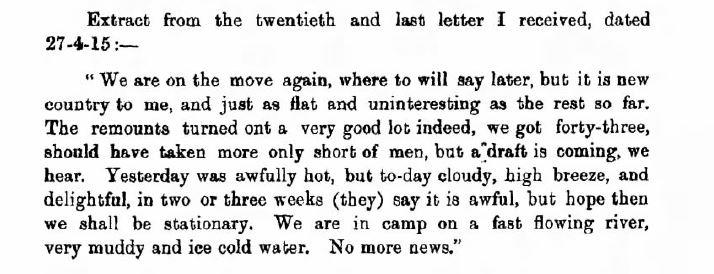

There is even more information available about Major Anderson, as the letters he wrote home were, post-war, published as a book which can be found in the Imperial War Museum, this book is now available from Naval and Military Press, but for those with full access to Fold3, this book can be freely accessed and downloaded from Fold3

Some extracts of the book are reproduced below which describe the last weeks and days of Major Anderson.

List of those killed in this action

Major Macclesfield Anderson: 33rd Queen Victoria's Own Light Cavalry

Lt Theodore Baliward: 26th King George's Own Light Cavalry (attached 7th Hariana Lancers)

Lt Alfred Le Mesurier: Indian Army Reserve of Officers (attached 33rd QVO Light Cavalry)

Lance Daffadar Ramdatt: 33rd Queen Victoria's Own Light Cavalry

Sowar Jaigram: 33rd Queen Victoria's Own Light Cavalry

Sowar Ramrichhpal: 33rd Queen Victoria's Own Light Cavalry

Assistant Armourer Abdul Ghani Khan: 7th Hariana Lancers

Conclusion

The Campaign in Mesopotamia, soon after the events described above, descended into disaster when – due to ‘mission creep’ - the ambitions of the local commanders were influenced by the seemingly easy victories that had been won.

Advances up the River systems in Mesopotamia were easy at first and capturing Ctesiphon[9] was expected to be the next victory en route to capturing Baghdad and damaging the Ottoman Empire. General Charles Townshend vacillated, sometimes supporting the advance and at other times having reservations. He ordered the 6th (Poona) Division of around 11,000 men, to advance north to Ctesiphon where they were stopped after several days of hard fighting by Turkish soldiers. Townshend was forced to retreat south in order to rebuild. By 6 December 1915, Townshend’s forces entered Kut.

The siege of Kut (7 December 1915 – 29 April 1916) and resultant surrender has been described by James Morris as “the most abject capitulation in Britain's military history”,[10] and caused the death or imprisonment of the entire garrison.

During the five month siege British commanders based in Basra launched a series of relief attempts to try free the surrounded garrison. Pushing north up the Tigris river, the closest attempt came to within hearing distance of the defenders of Kut before being beaten back. Ultimately, all attempts were unsuccessful and cost the British over 23,000 officers and men killed and wounded

After failed ceasefire negotiations with the Turkish commander, Townshend surrendered his depleted garrison on 29 April 1916, with approximately 13,000 British and Indian troops being captured. (This figure includes some 3,000 non-combatants such as camp followers and cooks.) Almost 4,000 died as prisoners of war due to a variety of causes, including malnutrition and abuse between capture and release in 1918.

The action of involving Anderson, Bailward and Le Mesurier was a small scale precursor to all that came later.

Why did Bailward end up being named at Basra and Anderson and Le Mesurier named on the Tehran Memorial? That remains unknown but more than likely is a combination of the confusion of the campaign, post war administrative muddle and the fact that the three officers were from different Cavalry regiments with two being ‘attached’ – one to the 33rd Cavalry and one to the 7th Hariana Lancers.

Further reading:

A Tour of Mesopotamian War Cemeteries in 2003

First World War Graves and the Memorial to the Missing in Persia

YouTube: Crisis at Kut 1915-1916 by Alan Wakefield

Oral History (interview): Henry Edward Shortt (attached to Queen Victoria's Own Light Cavalry) (full transcript below)

References

[1] The Campaign In Mesopotamia Vol1 1914-1918 By F J Mobberly. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.227118

[2] ‘Sowar’ means ‘one who rides’ and originally from Persian Sawar. ‘Sepoy’ comes from the Persian Sipahi meaning ‘infantryman’. They are of course the equivalent of a trooper and private respectively in the British Army.

[3] Sir Horace Anderson, Indian Army, had served in the Indian Mutiny of 1857 retiring in 1898. He died in 1907. His wife pre-deceased him, having died in Karachi in 1863.

[4] The ‘Port’ at Basra came much later. At the start of the war ships simply moored in midstream and were unloaded into local river craft. The port of Basra did not start to resemble a western port until the summer of 1916 when wharves were built and the port extended.

[5] "Arabistan" historically referred to the southwestern Iranian province of Khuzestan, particularly its Arab-populated areas. The term also encompasses the broader region encompassing parts of Iran, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia.

[6] https://houndwelfare.wordpress.com/2011/11/11/a-hunt-for-the-veterans/

[7] Source: https://rugbyschoolarchives.co.uk/RollofHonour.aspx?RecID=5&TableName=ta_rollofhonour&BrowseID=14

[8] This river is about 25 miles north-west of Ahwaz.

[9] This was a collection of ruins some 20 miles south east of Baghdad

[10] The surrender at Singapore in the Second World War, however, was arguably even more ‘abject’.

Becoming a member of The Western Front Association (WFA) offers a wealth of resources and opportunities for those passionate about the history of the First World War. Here's just three of the benefits we offer:

The WFA regularly makes available webinars which can be viewed 'live' from home. These feature expert speakers talking about a particular aspect of the Great War.

Featured on The WFA's YouTube channel are modern day re-interpretations of the inter-war magazine 'I Was There!' which recount the memories of soldiers who 'were there'.

Explore over 8 million digitized pension records, Medal Index Cards and Ministry of Pension Documents, preserved by the WFA.

Other Articles