Lt Col Thomas Wilton: ‘A VERY CAPABLE MAN’

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Lt Col Thomas Wilton: ‘A VERY CAPABLE MAN’

This familiar white Portland headstone of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission stands out amongst the sea of other graves at the huge Hendon Cemetery in north London.

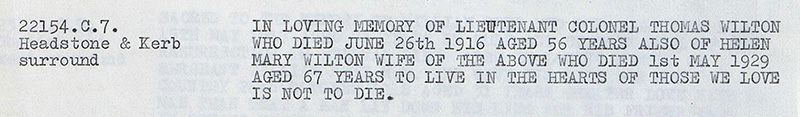

The inscription is clear:

Lieutenant Colonel T. Wilton

12th Battalion London Regiment (Rangers)

26th June, 1916

It's not uncommon, of course, to find First World War headstones in cemeteries in the U.K. because so many men were sent home for treatment, only to die in hospital, and others died in training accidents.

But this man was a very senior rank. And he died just before the start of the Battle of the Somme in 1916.

Why was he buried in Hendon?

The research trail produced a few surprises.

First surprise: Thomas Wilton was 56 when he died, which makes him one of the more elderly casualties to be commemorated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Second surprise: thanks to the website of the Greater London Industrial Archaeology Society (www.glias.org.uk) we learned that he didn't die on active service. In fact, he didn't see active service at all.

Thomas Wilton, I learned, was an important figure in London's industrial past.

He was born in the East End of London in 1860, and came from a family of engineers. His father was Superintendent of a Gas Works in North Woolwich Road – a path Thomas was soon to follow. By 1891, Thomas was manager of the massive Beckton Gas Works (or Beckton Products Works) on the northern shore of the river Thames.

The 1891 Census lists Thomas living at 51 Winsor Terrace, with his wife Helen Mary, two sons (Thomas and Norman) and two servants. Winsor Terrace still exists, although No 51 has disappeared. The house, though, would have stood next to a large entrance, with stone pillars and a metal grill, which still exists, and would have led to the huge works Thomas managed. This image is from Google Maps.

The Beckton Works, I learned from another website (www.eastlondonhistory.co.uk), covered 500 acres in London's East End and for decades, from the 1870s, it produced 5 million cubic metres of gas a day, plus a whole range of by-products like coal tar, dyes, disinfectants, ammonia and sulphuric acid.

Wilton was a prolific inventor, mostly of devices in the processing of by-products.

In 1899, for example, his name was attached to a patent for the ‘manufacture and purification of alkaline cyanides’, which would produce cyanides of better quality at minimal expense.

One account described him as ‘a very capable man, of great integrity who, though coleric at times, was just, forgiving and an untiring worker.’

Ahead of his times, he had X-Ray machines installed for the workforce.

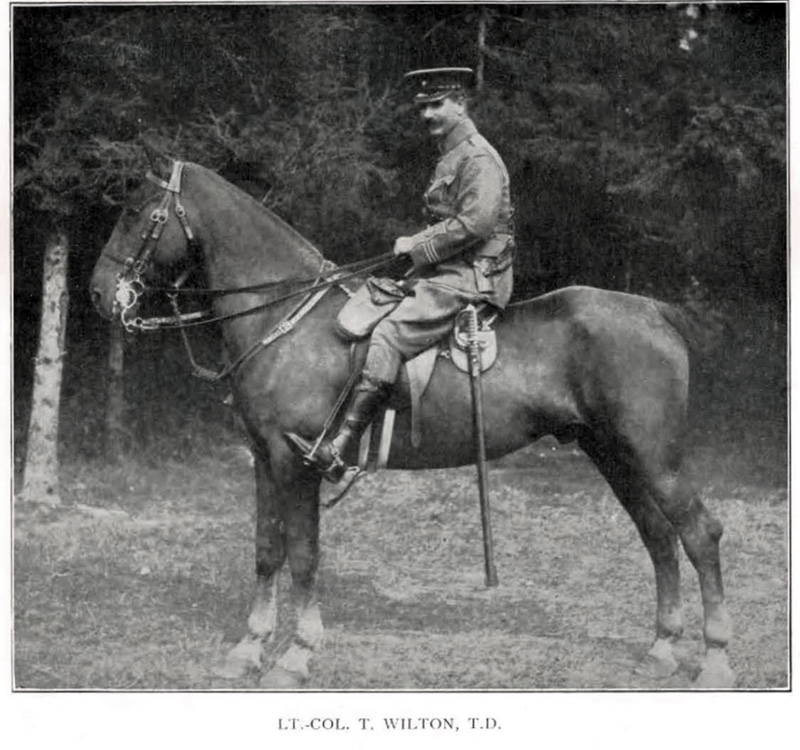

This portrait appeared before WWI in a journal called Co-Partners' Magazine, produced for the gas industry.

In the caption, Wilton is described as Superintendent of the Tar and Liquor Works, Beckton.

So what was the military connection, which would explain the Commonwealth War Graves Commission headstone?

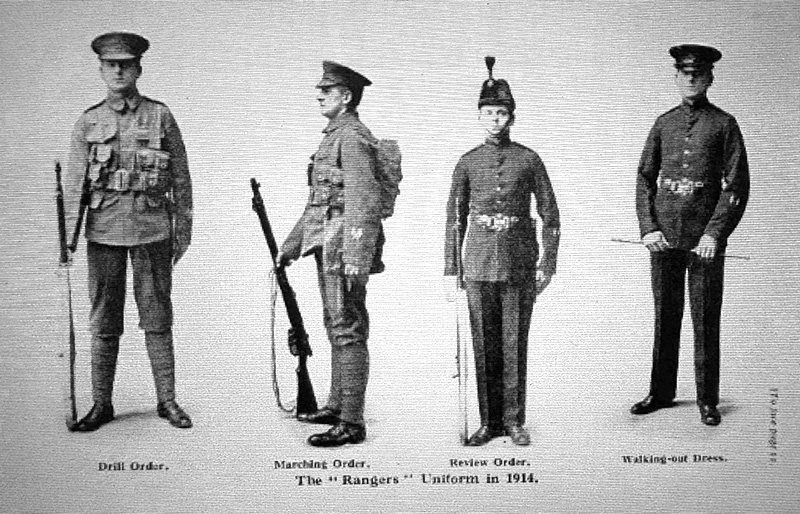

Wilton was active in the Territorial Army, and raised a company at the workplace, known as 'The Beckton Rangers'. He built a Drill Hall and rifle ranges on the site, and organised a company band. The unit provided troops for the South African War, and by 1913, Wilton was a Lieutenant Colonel, commanding the 12th Battalion, County of London Regiment (The Rangers).

A regimental history, The Rangers' Historical Records: From 1859 to the Conclusion of the Great War, published in 1921, said of him:

He was a most popular officer and under his command many improvements were made to the headquarters and to the Regiment.

He certainly took his overall regimental responsibilities seriously. A newspaper, The Standard, for example, reported in January, 1913, how Lt Col Wilton had presided over a Christmas party for more than 500 children at the regimental HQ in Chenies Street, just off Tottenham Court Road in London. It was, according to the reporter, exceedingly happy. The children were treated to tea, then a film show ‘showing life in the Navy and Army, besides incidents at camp,’ followed by a conjuring display, and gifts to every child. Officers dressed as Father Christmas and a clown ‘caused roars of laughter.’ As they left – at nine o clock – each child was handed a parcel of chocolate, buns and fruit.

The site of the headquarters where the children had such a good time has disappeared, but is now marked by a memorial to the Rangers.

Behind it: the Eisenhower Centre, a fortified Allied communications base during WWII.

The Co-Partners' Magazine carried reports about the drills and camps and social life of The Rangers in the years before WWI. The photograph below was taken at Bustard Camp on Salisbury Plain in 1909.

As Battalion Commander, Lt Col Wilton was one of the first to be mobilised in 1914, but while training at Bullswater Common near Pirbright in Surrey he was found to be medically unfit for service overseas.

In September, 1914, he took command of a second line Battalion being formed and trained in Regent's Park, and then White City.

But in March, 1915, the 'vacant command' was taken by another officer, so presumably Lt Col Wilton was very sick by then. His resignation from his job at Beckton was accepted in July, 1915, ‘with great regret' by the Directors.

‘There is no doubt,’ the Co-Partners' Magazine said, ‘that Mr Wilton's health was much impaired by the whole-hearted energy he devoted to his military duties. As Lieutenant Colonel of the 'Rangers' he was mobilised at the outbreak of war, and from that moment until prohibited by the doctors he gave himself unceasingly to the service of the distinguished Territorial regiment which it was his privilege and pride to command.’

Wilton died on June 26th, 1916, at Rodborough Road in Golders Green. His son Norman was present. The cause of death on the certificate was given as 'morbus cordis', or heart disease. Probate records show that Thomas left an estate of £6,535, which would be worth about £750,000 today. His funeral was attended by several Staff Officers from the Regiment.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission explain that they commemorate military personnel who die after being discharged if they died from a disease contracted while in service – or if the disease was aggravated by their service. This clearly applied to Lt Col Wilton.

The CWGC headstone clearly marks Thomas's resting place at Hendon Cemetery. But burial records indicate that he was later joined by his wife Helen, who died thirteen years after Thomas, in 1929, and refers to a headstone and kerb surround with an epitaph. Of that, there is no trace.

Andy Milne, Head of Cemeteries and Crematoria at Hendon, explained that in the 1970s, the London Borough of Barnet decided to convert Hendon Cemetery to a "lawn principle” cemetery, with headstones only – no large kerbs. Many had fallen into disrepair and were removed.

The original headstone was installed on August 21st, 1916, and removed under the conversion to a lawn cemetery programme on September 26th, 1972. CWGC headstone was installed on September 19th, 1986.

As far as we are concerned, Andy says, there was never any reinterment and both Thomas Wilton and his wife are buried, undisturbed in their original grave.

Andy added that before she died, Mrs Wilton lived at the Holloway Sanatorium in Virginia Water in Surrey. She was 67.

The site of Wilton's Beckton Products Works became derelict in the 1970s, and was famously used as a film set, masquerading as Vietnam in Stanley Kubrick's Full Metal Jacket, and appearing in the James Bond film For Your Eyes Only.

It's now mostly built over, but the so-called ‘Beckton Alps’ is still a feature in that part of London.

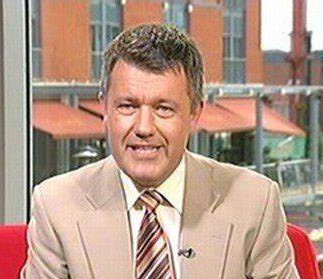

In researching this history, genealogist and military historian Dr Alan Hawkins was able to trace a direct line of descent from Lt Col Wilton which led us to his great great grandson, Michael Collie, a broadcaster based in the Midlands. Michael's grandmother, Peggy, was the daughter of Norman Wilton, Lt Col Wilton's son, who was with Thomas when he died.

Michael said he'd always known that somewhere in his ancestry there was an inventor. ‘But now,’ he says, ‘I know so much more. Thomas Wilton worked in an industry at a time when new inventions and ways of dealing with new challenges were essential, as industry developed and the population of London grew. Thomas Wilton certainly played his part. For me, the link is very special.’

By an extraordinary coincidence, Michael was an Army Reservist for 30 years, even working with the London Regiment, and spent time at Regent's Park Barracks, where his great great grandfather was based during part of his service with the Rangers. In addition, Michael has a flat in Silvertown, extremely close to the site of the old Beckton Gas Works, his great great grandfather's domain.

Michael also appreciated learning that his great great grandfather has a military grave in London; as a teenager, he helped maintain Commonwealth war graves, when he lived in Sheffield.

Here in my ancestry is a man with whom I have those and many more connections, and yet I knew virtually nothing about him. But now I do. Our family have now gained knowledge of our own history, but this is not just history for us. Without a doubt, Thomas Wilton made a difference for so many people. We now know a little of the person he was, his leadership, his character, and his achievements for London and the people with whom he worked and about whom he clearly cared. I hope that Thomas Wilton will remain an inspiration not just for our family but for everyone who reads about this extraordinary inventor.

As the epitaph said on the lost family tomb in Hendon Cemetery, according to the burial register:

To Live in the Hearts of Those We Love is not to Die

Article submitted by Rob Kirk.

Special thanks are due to fellow historians Dr Alan Hawkins, John Taylor and Michael Gilbert, to Michael Collie, to the website East London History, to the Greater London Industrial Archaeology Society, to Professor Russell Thomas who provided the portrait of Lt-Col Wilton, and led us to the industry magazine, to Andy Milne of the Hendon Cemetery and Crematorium, and to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.