‘THE GIFT OF HER SORROWING PARENTS’

- Home

- World War I Articles

- ‘THE GIFT OF HER SORROWING PARENTS’

The Great War still casts long shadows, even more than a hundred years on, and often in the most unexpected places. Most parish churches, for example, contain a memorial of some kind, and it’s not uncommon to be reminded that women were among the victims, and not all the deaths were caused by bombs, bullets or disease.

This, for example, is the medieval church of St Oswald’s at Grasmere in Cumbria.

It’s Grade I-listed. It’s where William Wordsworth worshipped, and the poet is buried in a family plot in the graveyard.

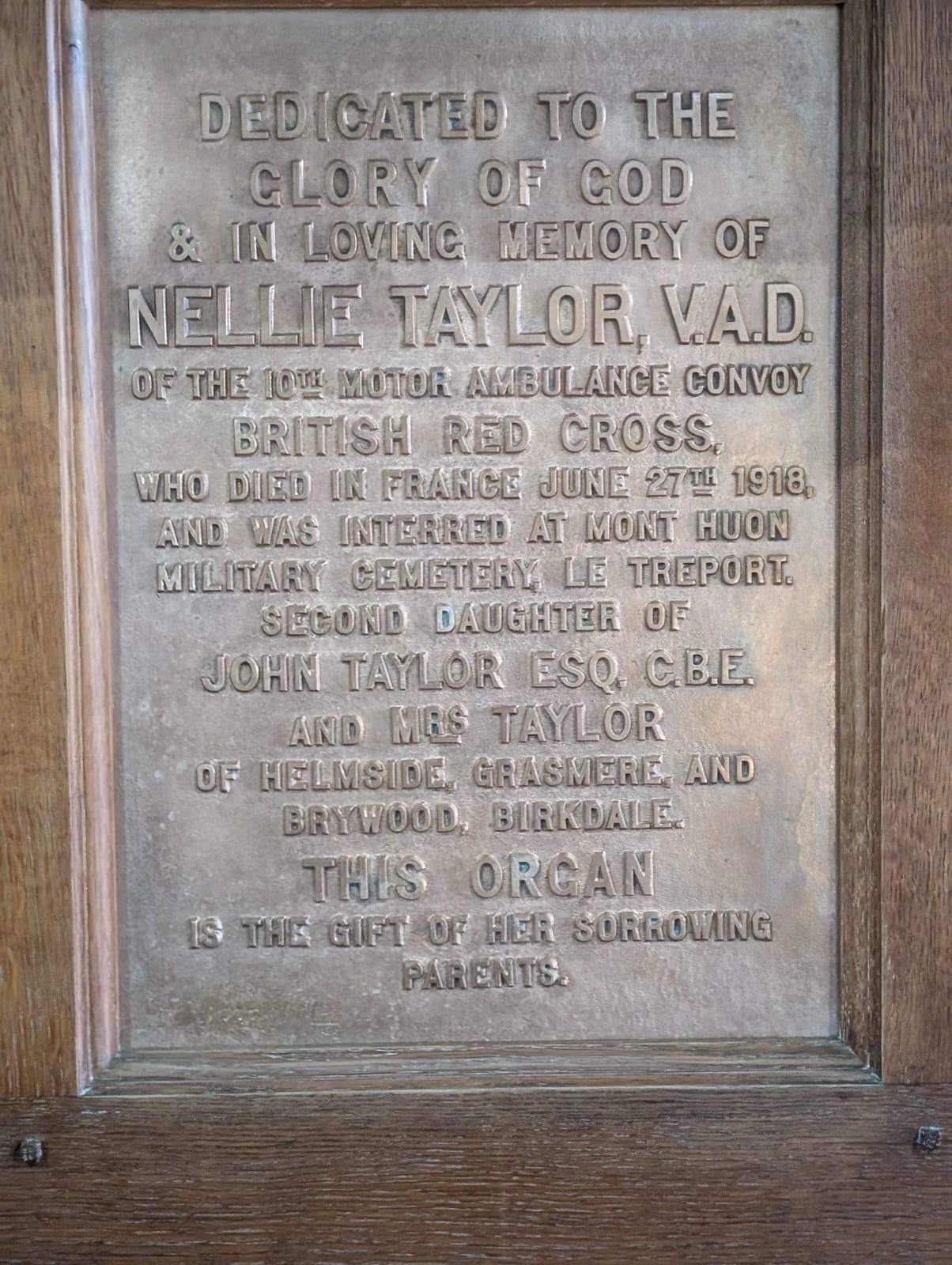

But inside, there’s a memorial to a young woman, Nellie Taylor, whose parents John and Mary, paid for an organ at the church in her memory because she was a gifted musician. Nellie was with the VAD – the Voluntary Aid Detachment – attached to the 10th Motor Ambulance Convoy of the British Red Cross.

She was a driver, and died in June, 1918, at the age of 30. Nellie is buried at a military cemetery in France, but the circumstances of her death hint at a painful background story.

A very helpful contribution to the story of Nellie Taylor was made in 2019, when a contributor called Marilyne remarked on the Great War Forum site that she’d been reading A Nurse at the Front: the First World War Diaries of Sister Edith Appleton, edited by Ruth Cowen, and published by Simon and Schuster in 2012.

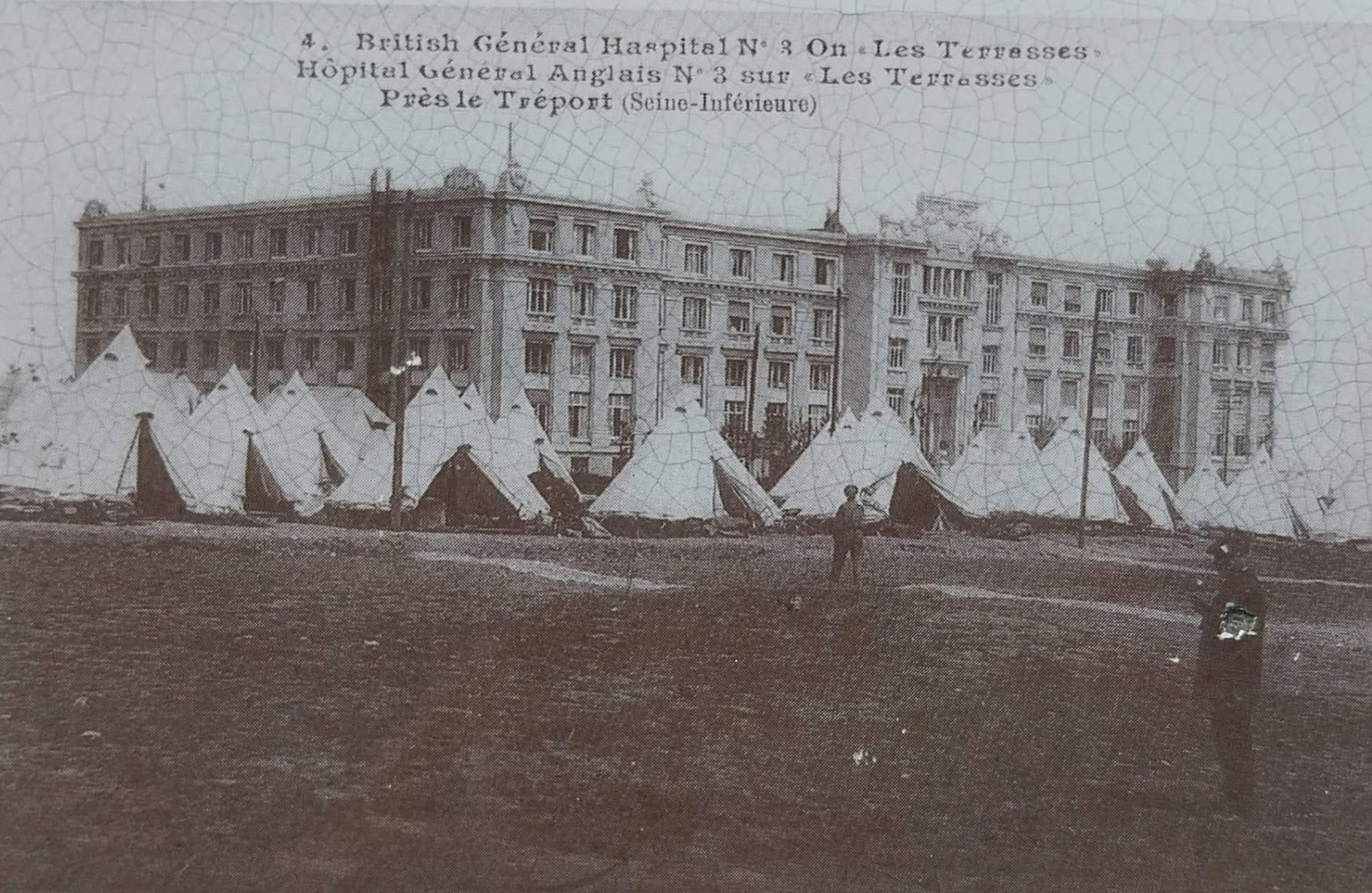

Marilyne noted that Sister Appleton, who served in France and Belgium for the whole war and whose bravery was recognised with many awards, was at the No 3 General Hospital in Tréport in 1918. On June 28th, she noted in her diary:

A sad tragedy happened at five yesterday afternoon. A mental patient – a lady driver – managed to dodge her special attendant and fling herself over the cliff. Her body was soon picked up, quite smashed in every part. She evidently meant to do it as she had left letters for people telling them so. It is said she had a similar attack a few years ago and her father insisted on her coming out to France to work. I think, if he knew her tendency, it was wrong to allow her to be in charge of helpless men at any time.

Sister Appleton also recorded the funeral. Her diary entry for June 30th is disapproving:

The poor suicide girl was buried yesterday, and to my way of thinking far too much of a pageant was made of it. There was a long procession headed by the convalescent camp band, then the ambulance with the coffin, smothered with flowers, then all the drivers – about 40 of them. There followed the girl’s own car, also full of lovely flowers, then big contingents of MOs and sisters from 47 General Hospital, our own hospital, the Canadian and American hospitals, men from the convalescent camp, then our own Colonel and Surgeon General, then the three commandants of the drivers. There must have been about 300 people. The French photographers were all over the place taking photos for postcards! If I were her people I should be heartily disgusted at the whole thing. A quiet funeral would surely have been more comely.

Despite her full account of the death and the aftermath, Sister Edith mentions no name. But the dates match the known narrative perfectly, and Nellie is buried at the military cemetery at Mont Nuon, on the outskirts of Le Tréport, so we can be reasonably certain that the diary is referring to Nellie.

Jim Strawbridge, another contributor to the Great War Forum, made a further telling contribution when he discovered a record of Nellie’s death in the diary of Maud McCarthy, the Matron-in-charge of the British Army (National Archives, WO 95/3990). In her summary for the month of June, 1918, this formidable woman recorded:

Died - Miss N. Taylor BRCS Motor Convoy Driver (Melancholia) on 27.6.18

So even though to date, no death certificate has been discovered, the evidence from two very senior nurses, Maud McCarthy and Edith Appleton, supports the idea that it was indeed Nellie who took her own life. Note the reference to ‘melancholia’.

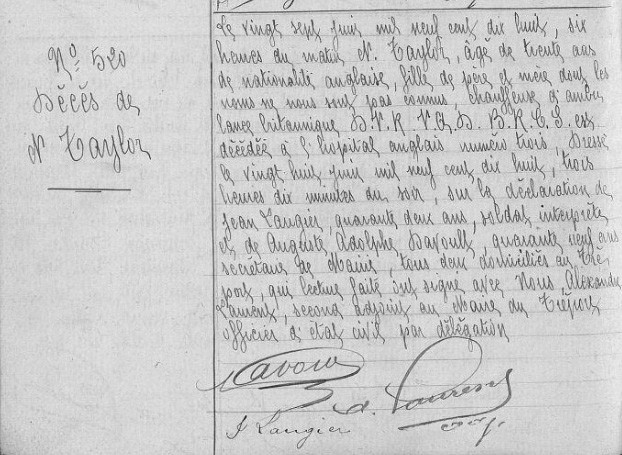

Another piece of evidence came from genealogist and historian Dr Alan Hawkins, who traced this document, known as a Death Record, in the archives of the Seine-Maritime Department in France.

The document doesn’t give a cause of death, but it does tell us that Nellie died at ‘trois heures dix minutes du soir’. This literally means ten past three in the evening, but in this context the writer is probably referring to the afternoon. The timing is slightly different from the reference to five o’clock by Sister Appleton, but it’s close and the difference might be explained by the time it took for news of the death to spread.

Another contributor to the Great War Forum, known as ‘Padre Bill’, reported that in 2020, a collection of letters purportedly written by Nellie were sold on E-Bay. Perhaps these letters were those referred to by Sister Edith, suggesting Nellie’s inclination to commit suicide. It would be wonderful if those letters surfaced; they would tell us so much.

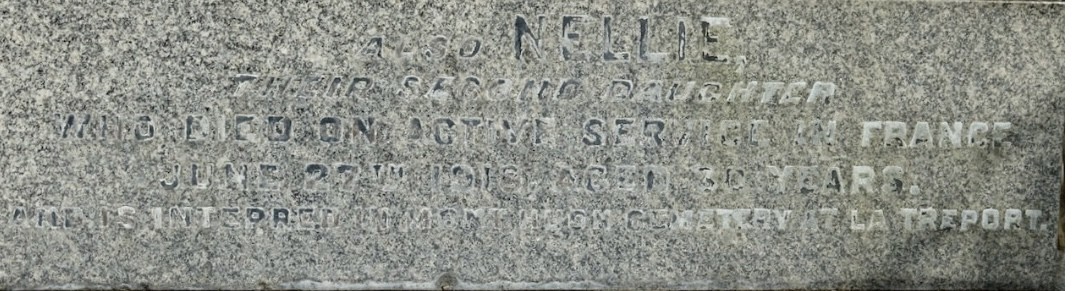

‘Padre Bill’ pointed out that in addition to the memorial at St Oswald’s in Grasmere, Nellie is also commemorated on the war memorial in Southport in Lancashire, and on her family tomb in Southport’s Duke Street cemetery.

He provided these photographs.

Touchingly, the barely legible inscription says she ‘died on active service’.

Nellie now rests at the Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery of Mount Huon on the outskirts of Le Tréport.

Her epitaph reads:

A blameless life

Cheerfully given to duty

At her country’s call.

Article submitted by Rob Kirk