The Kohima Epitaph: When you go home...

Most people recognise what we know as the ‘Kohima Epitaph’, which is a moving and familiar part of every remembrance service:

When you go home, tell them of us, and say

For your tomorrow, we gave our today.

But I suspect that many, like me, will assume that because it’s called the Kohima Epitaph, it was created to memorialise the men who died in the savage fighting at Kohima, on the border of India and Myanmar, during World War II in 1944. Not so.

I learned this as a result of an unexpected encounter with a Commonwealth War Grave Commission headstone in the graveyard of the remote church of St Mary Magdalene at Great Hampden, in the rolling Chiltern Hills near Wendover in Buckinghamshire.

Here, I found this headstone for a young man called Lieutenant G.M.A. Hobart-Hampden, of the Royal Flying Corps.

The inscription told me that he died on September 17th, 1917. He was 21.

At the bottom of the stone are the words:

WHEN YOU GO HOME

TELL THEM OF US AND SAY

FOR YOUR TOMORROW

THESE GAVE THEIR TODAY

‘Hang on’, I thought. That’s the Kohima Epitaph. What’s it doing on a headstone for a man who died in the First World War? And what about that last line? It’s normally: We gave our today, not These gave their today. I was intrigued.

I have James Bruce, a researcher for the authorised history of GCHQ, to thank for putting me right. In 2017, he published an article on www.gchq.gov.uk about the full story behind the Kohima Epitaph. The words were indeed inscribed on the memorial to the 2nd Division at Kohima, but I learned that the epitaph was composed much earlier.

It was one of several created by a Cambridge classicist turned wartime codebreaker, John Maxwell Edmonds, who was born in Stroud in 1875. During the war, he and his wife Ethel worked in the War Office’s codebreaking bureau, called M.I.1 (b), which became a forerunner of GCHQ.

His first four epitaphs were published by The Times in February, 1918. They included one called On Some Who Died Early In The Day of Battle. It included the lines:

Went the day well? We died and never knew;

But well or ill, England, we died for you

These words were much used in newspaper memorial notices, and inspired the title of the 1942 Ealing film Went The Day Well?

Over the next year, Edmonds wrote about a dozen epitaphs and nine appeared in a publication from the Victoria and Albert Museum, called Inscriptions Suggested for War Memorials. One was intended For a British Graveyard in France:

When you go home, Tell them of Us, and say

For Your tomorrows, These Gave Their Today.

Note the use of the plural tomorrows, rather than the singular tomorrow. The change happened when the epitaph appeared in a 1920 publication calles Twelve War Epitaphs, but tomorrows had been changed to tomorrow. This, apparently, was done unilaterally by the printers or the publishers, and Edmonds was upset. He had further reason to be upset later, when his original words were changed from These Gave Their Today to the now familiar We Gave Our Today.

James Bruce remarked in his article that the revised words make the epitaph more of an invocation than a memorial inscription, as Edmonds intended.

It is, though, profoundly powerful and effective.

Edmonds died in 1958, at the age of 83.

But what about the young man whose headstone inspired this enquiry?

Apart from the inscription, I noticed another unusual aspect of the burial. Lieutenant Hobart-Hampden’s CWGC stone stands at the head of a family slab tomb; his name is engraved on it, badly eroded, and it’s just possible to make out other family names too.

Now, it’s not uncommon to find CWGC headstones in country churchyards. It’s also true that even where churches show small signs saying the graveyard contains CWGC burials, you won’t find a Portland stone headstone because the family opted for a family burial.

But it’s rare to find both. In fact, this is the first I’ve come across.

The first stop in enquiries like this is always the Commonwealth War Graves Commission’s website, www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead, and I was able to supplement information gleaned there with material from the Lives of the First World War on the Imperial War Museum website, from an exchange on the Great War Forum, and most of all, from a researcher called Andy Pay on buckinghamshireremembers.org.uk.

Taking it all together, I was able to build a picture of young George Miles Awdry Hobart-Hampden.

George was born in 1896 in India, where his father, Awdry George Hobart-Hampden, worked for the Indian Forest Service. His mother was Elsie Angel Heath Pitcher. Back home in the UK, George went to Rugby School on a Scholarship, and then to Brasenose College in Oxford on a Classical Scholarship.

On September 2nd, 1914, he enlisted with the Ox and Bucks Light Infantry, and sailed to France in March, 1915, where he was severely wounded in June. He rejoined his battalion in August, 1916, but was attached in December to the fledgling Royal Flying Corps as an Observer. He was with his squadron at the front until May, 1917, when he returned to England for a Pilot’s course.

George was with C Squadron at the RFC Central Flying School at Upavon in Wiltshire.

He’d just qualified for his pilot’s certificate, when he was killed in an accident on 17 September, 1917.

He was flying a S.E.5a (B9), a biplane fighter described since as ‘the Spitfire of World War One.’

The plane is said to have veered on take-off, and the wing and undercarriage hit the ground before it caught fire.

The Brasenose College magazine, The Brazen Nose, reported:

He was killed in a flying accident, by which several mechanics who were standing near must have been killed, had he not put his helm down hard, and saved their lives by the sacrifice of his own….

He was a true and brave soldier, and his life was full of promise…

It was not given to him to die at the Front, but in his death he showed the gallantry and unselfishness which had endeared him to his friends.

George was buried at the church of St Mary Magdalene at Great Hampden, where his father had been Hampden Estate Manager. A party of the Royal Flying Corps was present.

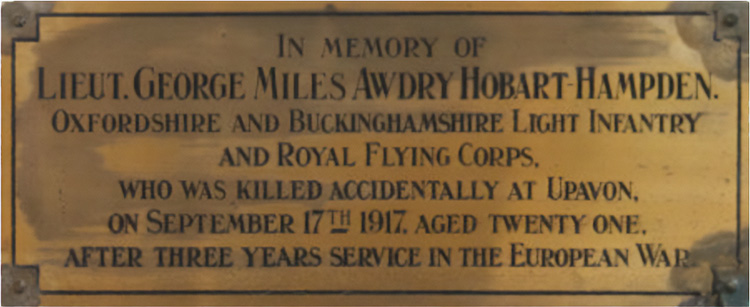

He is remembered with a plaque inside the church.

Becoming a member of The Western Front Association (WFA) offers a wealth of resources and opportunities for those passionate about the history of the First World War. Here's just three of the benefits we offer:

With around 50 branches, there may be one near you. The branch meetings are open to all.

Utilise this tool to overlay historical trench maps with modern maps, enhancing battlefield research and exploration.

Receive four issues annually of this prestigious journal, featuring deeply researched articles, book reviews and historical analysis.