Whipsnade Tree Cathedral: ‘Here was something more beautiful still…’

The man behind the Whipsnade Tree Cathedral was Major Edmund Kell Blyth, an officer with the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry.

He built it as a memorial to three of his Army comrades, Arthur Bailey and John Bennett who were both killed during the German Spring Offensive in 1918, and Francis Holland, who died in a post-war car crash.

The ‘Cathedral’ was intended as a site of faith, hope and reconciliation.

This article describes this extraordinary feature, and explores, as far as is possible, the stories of the three men who are commemorated.

You’ll find the Cathedral very near the edge of what is now Whipsnade Zoo, near where Blyth lived after he left the Army in 1922 and joined the family firm of solicitors in the City of London. In 1930, Blyth and his wife visited Liverpool Anglican Cathedral which was then being built. He later wrote that on their way home through the Cotswolds:

I saw the evening sun light up a coppice of trees on the side of the hill. It occurred to me then that here was something more beautiful still and the idea formed of building a cathedral with trees.

Work began in 1932.

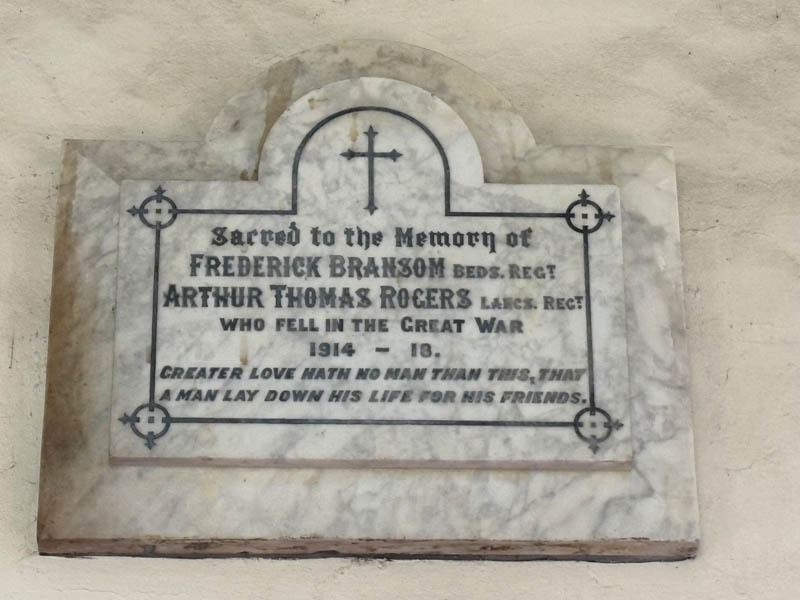

Edmund Blyth had the help of a local man, Albert Bransom, who lived with his wife Mary at Yew Tree Cottages, near to the modern entrance to the Cathedral. Their son Private Frederick Bransom of the 2nd Battalion, Bedfordshire Regiment, died on the Somme battlefield of his wounds on August 1st, 1916. He was 22 years old.

Frederick had been fighting at the now destroyed Maltzkorn Farm south of Trones Wood, near Guillemont. He was one of 186 other ranks and six officers noted as casualties in the War Diary, and is now buried at La Neuville British Cemetery at Corbie.

Frederick is also remembered in St Mary Magdalene, a largely 17th century church, which stands near the Tree Cathedral.

When news of Frederick’s death reached Whipsnade, a short obituary appeared in a local newspaper. It said:

He is the first from the parish to pay the deadly price of war, and a youth greatly loved and respected by all. For over nine years, he had worked on the land at Hall Farm, and those, who for various reasons, are precluded from an active part in this unprecedented world conflict, can well appreciate the immense shifting of outlook and vast upheaval of emotions that such a change in the life of a young man must mean. He went willingly to meet the foe of his King and country, and lay down his life in a good and honourable cause – a death above all others the most noble.

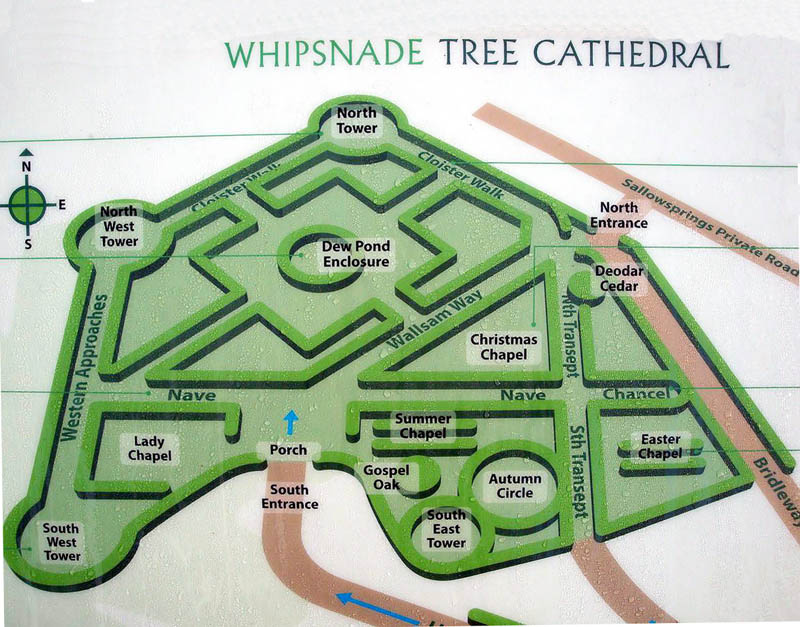

Over seven years, Blyth and Frederick’s father planted the memorial in the shape of a medieval cathedral. It covers about 20 acres.

The nave was the first to be planted, using poplars at 10ft intervals to give a pillar effect. The nave and chancel measure 128 metres – the length of nearby St Albans Abbey.

Two chapels filled in the corners between the nave and transepts – the Easter Chapel and Winter (now known as Christmas) Chapel; the Christmas Chapel is now planted with fir trees.

Blyth used silver birch to represent the High Altar in the chancel because of its gracefulness. A dew pond became the cloister walk, and three natural depressions made by farmers digging out chalk to lime the fields became the bases of towers.

Around the same time, the nave was extended with limes, and a fourth tower built to accommodate an existing oak, which became known as the Gospel Oak, recalling the preaching of early Christian missionaries under the trees. You’ll also find cedar, beech, yew, maple, Norwegian spruce, whitebeam, tulip trees, ash, birch, beech, cypresses and holly.

Work was completed in 1939 – just in time for the Second World War, when Blyth rejoined his regiment. Over the next eight years, the plantation was overgrown by thorn and other self-sown trees. When he returned from the military government of Berlin in 1947, Blyth organised its clearance during the late 1940s and early 1950s, and the reborn Cathedral was given to the National Trust by Blyth’s youngest son in 1960.

Edmund Blyth summed up its aims:

Although it contains beautiful areas, that is not its primary significance, and nor is it a garden. It is managed to emphasise the vigour and balance of individual plants, in patterns that create an enclosure for worship and meditation, offering heightened awareness of God’s presence and transcendence.

The Cathedral is now registered as a Grade II listed site by Historic England. It’s unconsecrated, but an interdenominational service takes place every year. The only addition was a hornbeam avenue from the small car park, in memory of Blyth’s son Tom, who managed the Cathedral after his father’s death in 1969 until his own in 1978. The National Trust took over full managership in 2023.

What do we know about the three men Edmund Blyth memorialised at the Tree Cathedral - Arthur Bailey, John Bennett and Francis Holland?

Genealogist and military historian Dr Alan Hawkins established a strong connection between Blyth and two of the three - Bailey and Holland. All three served in D Company, 2nd Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry. An officers’ roll in December, 1917, in the battalion war diary, shows Blyth and Bailey together. Bailey died on 24th March, 1918, and Blyth rejoined D company on 6th April, 1918, after a spell in hospital; Holland joined D Company on 17th October, 1918.

2nd Lt Walter Arthur Francis Bailey attended Shrewsbury School and entered Sandhurst as a prize cadet in 1916 at the age of 17. He was 19 years old when he died. He’s commemorated in several places, including in a black leather book of remembrance in St Stephen’s church, Bournemouth, by a seat in the Ox and Bucks regimental chapel at Christchurch Cathedral, St Aldates in Oxford, and in the Shrewsbury School Chapel, and in the Memorial Chapel at Sandhurst, pictured here. His name is on the Arras Memorial to the Missing.

2nd Lt Francis Culyer Holland, widely known as Frank, was indeed killed in a car crash, in late 1928, in Victoria, Canada. An article in a newspaper reported that he was the chairman of the local Toc H organisation, and his funeral was carried out with ‘Toc H rituals’. Among the tributes was a replica of the ‘Ypres Cross’ with red carnations and white chrysanthemums from Toc H. His wife, Sylvia Moberly, was an animation artist for Walt Disney.

Finding ‘John Bennett’ proved more difficult.

Understandably but maybe erroneously, we made an assumption that Bennett would have been an officer. But only five officers known as ‘John Bennett’ died in 1918, and of those five, only two were killed in the German Spring offensive. One of these was in the Royal Flying Corps, and as far as we could tell, had no common ground with Edmund Blyth.

So who was the other ‘John Bennett’ – the man known to Edmund Blyth and possibly memorialised at the Tree Cathedral?

Alan came up with a possible name: John Benson Bennett, a 2nd Lt with the 3rd Rifle Brigade, who died on March 28th, 1918, aged 22. With help from the sleuths in the Great War Forum, we were able to flesh out more details. This John Bennett came from Gorseinon in Glamorgan. He went to Gowerton County School and University College, Swansea, and enlisted in November, 1915, in the Welsh Regiment, serving in France in 1916. He was gazetted as a 2nd Lt in the Special Reserve in June, 1917, before moving to France and joining the 3rd Rifle Brigade in August.

If this is our man, how did he and Blyth know each other? Blyth, after all, was in the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry and Bennett was in the Rifle Brigade. If they were acquainted, it’s likely that they met in training, perhaps at an Officer Cadet Battalion, or at Sandhurst, or perhaps elsewhere. Unless someone produces new evidence, we might never know.

Footnotes

- At one stage in our research, we thought we had identified a potential ‘John Bennett’ in the 2/4th Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry. He was a Major, who won a Military Cross. This ‘John Bennett’ was called ‘Herbert John Bennett’, but Alan Hawkins’ wife Margaret discovered on the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry website that Herbert preferred to be known as ‘Jack’, a well-known form of ‘John’. There was, however, a problem: this ‘Bennett’ was taken prisoner on 30th March, 1918, when the war diary lists him as ‘missing’. Red Cross records show that he was held in Salzburg, and repatriated in December, 1918. So not only did this Bennett survive the war, but he returned to live with his wife in Oxford, which we must assume Blyth was aware of – if he knew Major Bennett at all.

- Francis Holland’s brother, John Dixon Culyer Holland, was also a 2nd Lt in the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, and was killed on November 13th, 1916, at the age of 25. He’s buried at Munich Trench British Cemetery at Beaumont Hamel.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the National Trust for the picture of Edmund Blyth, the illustrated map of the Tree Cathedral, and for information on the NT website, and to Sandhurst for the picture of Walter Bailey’s memorial seat. Also to David and Julie Thomson at La Boisselle for the photograph of Frederick Bransom’s headstone, and to Geoff Meade for his views of the Tree Cathedral. Thanks, too, to the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry website, to Alan and Margaret Hawkins for their excellent research, to the Bedfordshire Archives, to local historian Nigel Lutt for drawing attention to the newspaper obituary, and to the incredibly informed participants of the Great War Forum.

Becoming a member of The Western Front Association (WFA) offers a wealth of resources and opportunities for those passionate about the history of the First World War. Here's just three of the benefits we offer:

With around 50 branches, there may be one near you. The branch meetings are open to all.

Utilise this tool to overlay historical trench maps with modern maps, enhancing battlefield research and exploration.

Receive four issues annually of this prestigious journal, featuring deeply researched articles, book reviews and historical analysis.

Other Articles