A Testament of Youth by Vera Brittain

- Home

- World War I Book Reviews

- A Testament of Youth by Vera Brittain

Feminism of the First Hour?

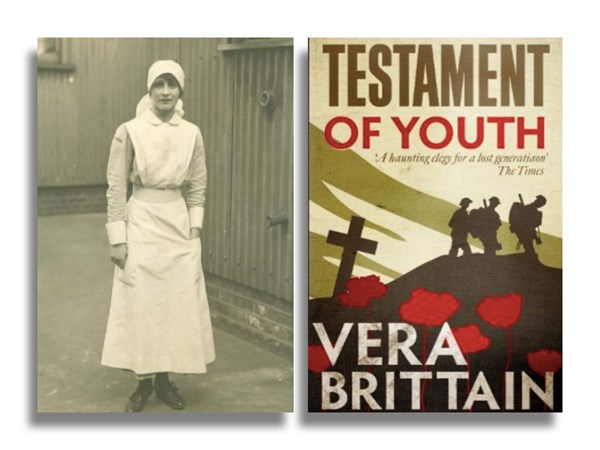

Released in 1933 as Germany faced the beginnings of the rise of fascism, A Testament of Youth recounts the First World War as years of love, desolation and loss leading to a life of pacifism, through the personal narrative of Vera Brittain – a fiancé in waiting turned volunteer nurse.

As a middle-class girl from Derbyshire, Brittain was raised in an Edwardian society whose places for intelligent women were seldom. The First World War came when she turned twenty years old and, as such, she narrates the conflict with a desolate wisdom overseeing the apocalypse of an entire society already struggling with unresolved class and gender imbalances – something Brittain views as a contributor to the nation’s approach to its military conflict. How ironic that perhaps one of the greatest written accounts of lived experiences of the First World War comes not from a working-class male in the trenches on the Western Front, or from a bourgeois politician or general privy to negotiations, but from a woman in the centre of domestic conflicts.

At the start of the war, Brittain’s fiancé goes to war, and she is left at home waiting anxiously. Desperate to help in the war effort, despite being accepted to the University of Oxford to read literature in the face of her parents’ protestations and the restrictions of societal norms, she left her studies to pursue the demanding work of Voluntary Aid Detachment. Volunteering to nurse the wounded in London, Malta and eventually the Western Front, a previously repressed middle-class young woman now was exposed to the fully anatomy of men. She draws attention to women’s fashion at the time as having been “designed by their elders on the assumption that decency consisted in leaving exposed to the sun and air no part of the human body that could possibly be covered with flannel” and describes her attraction to her fiancé Roland as primarily intellectual and artistic with little to no physical contact. Contrastingly, as soon as she signs up to the VAD, she begins treating venereal disease in soldiers, mopping up pus and vomit, stripping men naked and assisting limbless men in urinating. Given her ignorance to the male anatomy, the emotional impact of this exposure to male bodies in their rawest form heavily influenced Brittain’s prose regarding the male body and the description of love. She was determined to say, with as little graphic detail as possible, what was traditionally unsaid at a time with little convention for sexual prose, to allow for sufficient understanding of the female experience of war. We, the reader, are able to understand her processes, her thoughts and her emotions. Taking this into account, the following passage is all the more sensitive:

“In the early days of the War the majority of soldier-patients belonged to a first-rate physical type which neither wounds nor sickness, unless mortal, could permanently impair, and from the constant handling of their lean, muscular bodies, I came to understand the essential cleanliness, the innate nobility, of sexual love on its physical side. Although there was much to shock in Army hospital service, much to terrify, much, even, to disgust, this day-by-day contact with male anatomy was never part of the shame. Since it was always Roland whom I was nursing by proxy, my attitude towards him imperceptibly changed; it became less romantic and more realistic, and thus a new depth was added to my love.”

After the armistice, Brittain was alone and tenderly felt the absence of the men in her life, writing that “there seemed to be nothing left in the world, for I felt that Roland had taken with him all my future and Edward all my past.” She had lost four men, including her fiancé and her brother. Although this was not a unique experience, she beautifully recounts the prolonged apprehension of waiting for the news of death of loved ones, stating that even in 1933 (the time of writing) she could not sit in a room where it was possible to hear the doorbell ring. Upon returning from her duties in the VAD, she continued her studies at the University of Oxford, and switched to reading History before working closely with the peace-keeping organisation, the League of Nations, becoming a supporter of both the feminist movement and the pacifist movement. She then marries a political science academic called George Catlin who lived through, understood and was changed by the war in the same manner as herself. This turbulent period of positive transition in her life is reflected in her narrative as Brittain critically details key dates, names and events including the Treaty of Versailles and the shortcomings of the League of Nations, providing an elasticity to the history we think we know.

Brittain’s narrative purposely does not end in 1918 at the end of war, but in 1925 whereby the schism between her pre-war and post-war self is distinct. Travelling with the League of Nations in 1924, she sees first-hand the lasting destruction of war in Eastern Europe and is able to identify that the destruction has not yet ended. She has reached a reflective state of self in which she can posit where society, and her place in society, may progress or regress to next…

“It did not seem, perhaps, as though we, the War generation, would be able to do all that we had once hoped for the actual rebuilding of civilization. I understood now that the results of the War would last longer than ourselves; it was obvious, in central Europe, that its consequences were deeper rooted, and farther reaching, than any of us, with our lack of experience, had believed just after it was over.”

Review by Chloe Egan

Secondary School History Teacher, Liverpool City & Beatles Tour Guide, Western Front Association member