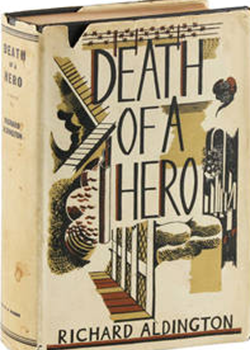

Death of a Hero by Richard Aldington

- Home

- World War I Book Reviews

- Death of a Hero by Richard Aldington

Published by Chatto & Windus

London, 1929

With reference to an unabridged edition.

Paperback, 376 pages

Published 1984 by Hogarth Press

Death of a Hero by Richard Aldington

Published by Chatto & Windus, London, 1929

Aldington, an experienced and successful poet, journalist, translator and critic wrote his first novel Death of a Hero in haste, his tone of frustration set from the start. Though labelled fiction he draws closely on his own life with the protagonist ‘George’ very much the young Richard serving during the First World War.

Death of a Hero is a book in three parts; the first addresses his precarious background as the child of a middle-class family with pretensions to gain and maintain an upper middle-class lifestyle which goes awry; the second part addresses his years in London before the war having to give up his place at university and find work and the third his experience as a soldier during the First World War.

Aldington wrote Death of a Hero a decade after the Great War having become a successful Imagist poet, an established critic, accomplished translator, writer and sometimes editor. He was obliged to enlist late (mid-1916) as a private under the Derby Scheme (being a married man). In Death of a Hero he was able to put into words the shock of training (where the most onerous and odorous tasks reduced him to tears), then receiving a commission, going through officer training, then the ins and outs between rest, in reserve, or in the front line and, of course, the intermittent short-lived climax - the experience of battle and then its aftermath.

However, as pointed out, ‘war years’ is just one section out of three that make up Death of a Hero.

Part I is a protracted character assassination of his parents and their respective families in a rail against his own stuffy and precarious middle-class background with its social mores, hang-ups and constraints. When his father’s legal practice and dealings failed the young Aldington was pulled out of university and age 18 had to fall back on his own wits to avert the blight of a clerk’s desk in the city. He writes like an angry young man, embittered by his lot, the life chances handed him and as his relationships with members of the opposite sex develop, anger at a society that failed to teach its young people even the basic mechanics of sex.

In the early passages (Part I of Death of a Hero), Aldington shows how aggrieved he felt by the hypocrisy of British society (or at least the part he belonged to) being so obtuse about sex and sex education its physiological execution, let alone its psychological impacts and purpose. Yet he wished to write of fumbling adolescent sex, about not knowing how to pleasure a girl as well as the ignorance of his parents when they married. For example, there’s a passage in which George (Aldington’s alter ego in Death of a Hero in which he doesn’t know what to do when the girl he is kissing passionately, invitingly and in hope and expectation, spreads her legs. (Willis, 1999 p.480) Willis, 1999, p.480 describes these as ”Lawrentian affectations bitter digressions, laboured satire.”

It is as if Aldington is calling for a sex manual, not that there were many of those around in the 1920s, or a few decades earlier for his parents' benefit, in which the narrator furiously argues for knowledgeable adult sexuality, knowledge of a woman’s body, her hymen, orgasms, periods, and possible pain during intercourse, or how to postpone conception. These illusions to sex, sexual arousal and fulfilment and particularly sexual relations outside marriage and the words and phrases required, risked prosecution under Obscenity Laws of 1887 and had to be severely redacted to permit publication in Britain and the US. Knowing D.H.Lawrence closely Aldington was aware of the near ruin the criminalisation of Lady Chatterley's Lover inflicted on Lawrence financially and reputationally.

‘Death of a Hero’ is unexpected, candid, philosophical, controversial, and to the uninitiated reader, messy in its so-called ‘jazz’ style which is both loquacious and rambling, cerebral and crude. The personal relationships described are equally complex and ambiguous, truer to life in their messiness than a novel’s archetype of a protagonist and heroine. As Aldington (1929) p.68 wrote "The only books which have the least importance are those which are made from direct contact with life, which are built out of a man's guts". He adopted a more conventional and readable style to his later novels and short stories.

Aldington could not write 'Death of a Hero' he wished, though he did strongly desire to be published and to accommodate, however reluctantly, the wishes of his publisher. He was after all a professional writer who lived off his income from translations, editing and criticism. Willis (1999) describes the first edition of Death of a Hero as "scarred with asterisks rendering the occasional sentence and some passages unintelligible." This is true, as whilst it may be easy to figure out the single expletive and crude word, entire sentences are lost. Crude language and bawdiness is suggested - eroticism and ‘free love’ outside marriage removed.

Aldington, in the voice of his protagonist George, is cynical, observant, witty and cruel. Never as guttural, crude or sex-obsessed as Henry Miller (someone he later met in California through an introduction by Lawrence Durrell) (1). It's nonetheless worth making comparisons with other writers of the last century who wrote about the fighting man in a fresh voice, for example, Norman Mailer in his war novel The Naked and the Dead (1948) which also struggled with the censor - with the 'f word' that is forever redacted, Mailer opting for ‘fecking’ over Aldington’s use of ‘mucking’.

Death of a Hero is a tour de force, where a form a 'jazz writing', journalism embellished and brought to life as fiction.

"The problem facing the young war novelists in the 1920s" wrote Willis (1999 p.470) "was how to be faithful to the bitter, life-changing experience of modern warfare in a realistic depiction of both action and dialogue. The war had altered forever the perceptions of soldier-writers … "

Aldington had a number of things to get off his chest and the matter of sex and personal relationships to tackle as well as the war, but when he settles into it, there are lines of poetry which provide a vivid, convincing landscape to the Great War and where he served.

There are many insights, not least of the public school boy type who "could be implicitly relied upon to lead a hopeless attack and to maintain a desperate defence to the very end - there were thousands and tens of thousands like him." (Aldington, 1929 p.332) And then about bravery, writing that "It is absurd to talk about men being brave or cowards. There were greater or less degrees of sensibility, more or less self-control. The longer the strain on the finer sensibility, the greater the self-control needed. But this continual neurosis steadily became worse and required a greater effort of repression." (Aldington, 1929, p.333)

He shares painful events, details about having to deal with soiling his pants while out with a wiring party or getting back the wounded, and of course he writes vividly about what he sees, smells and hears. “Suddenly he was wide awake and sitting up. What on earth or hell was happening? From outside came a terrific rumble and roaring, as if three volcanoes and ten thunderstorms were in action simultaneously. The whole earth was shaking as if beaten by a multitude of flying hoofs, and the cellar walls vibrated." (Aldington, 1929.p.372).

And of course, he writes about death: “Already in this first half-hour of bombardment hundreds upon hundreds of men would have been violently slain, smashed, torn, gouged, crushed, mutilated.” (Aldington, 1929 p.373)

Death of a Hero is good as the best, say All Quiet on the Western Front or Her Privates We, just ensure that you purchase an unexpurgated copy.

(1) With thanks to Vivien Whelpton for pointing this out and adding that this is a photograph of Aldington with Henry Miller in part II of Richard Aldington: Poet, Soldier and Lover 1911-1929.

Reference

Aldington, R ‘Death of a Hero' (1929. Unexpurgated edition 1965). London: Sphere Books, 1968

Ayers, David S (1998) Richard Aldington's Death of a Hero: A proto-fascist novel. English, 47 (188). pp. 89-98. ISSN 0013-8215. (doi:10.1093/english/47.188.89) > English: Journal of the English Association, Volume 47, Issue 188, Summer 1998, Pages 89–98, https://doi.org/10.1093/english/47.188.89

Willis, J. H. The Censored Language of War: Richard Aldington’s Death of a Hero and Three Other War Novels of 1929. Twentieth Century Literature, vol. 45, no. 4, [Duke University Press, Hofstra University], 1999, pp. 467–87, https://doi.org/10.2307/441948.

Whelpton, V. Richard Aldington: Poet, Soldier and Lover 1911-1929 (Part I) The Lutterworth Press (2013)

Works by Richard Aldington published by William Heinemann.

Fiction

Seven Against Reeves

Very Heaven

Death of a Hero

The Colonel's Daughter

Soft Answers

All Men Are Enemies

Verse

The Crystal World

A Dream in the Luxembourg

The Eaten Heart

Life Quest

Imagist Anthology, 1930

Fifty Romance Lyric Poems. Chosen and translated by Richard Aldington

Belles Lettres

Artifex: Sketches and Ideas

The Spirit of Place: selections from D. H. Lawrence by Richard Aldington

Stepping Heavenward

D. H. Lawrence

Medallions. Translated by Richard Aldington

The Alcestis of Euripides. Translated by Richard Aldington.

Letters to the Amazon. By Remy de Gourmont. Translated by Richard Aldington.

Selections from Remy de Gourmont: CHosen and translated by Richard Aldington.

Voltaire: Biography