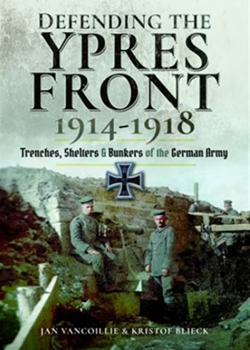

Defending the Ypres Front 1914 – 1918: Trenches, Shelters and Bunkers of the German Army

- Home

- World War I Book Reviews

- Defending the Ypres Front 1914 – 1918: Trenches, Shelters and Bunkers of the German Army

By Jan Vancoillie & Kristof Blieck

Pen & Sword, £25.00 (E–book: £14.40), 294 pp, ills, 34 maps, bibliog., index.

ISBN: 978–152–670–746–8

In outline this comprehensive book describes the German structures employed to defend the territory captured around Ypres and makes excellent use of official drawings and maps as well as photographs from the authors’ collections.

However, Defending the Ypres Front offers much more. The introduction explains how the German front line in Flanders came into being followed s descriptions of various aspects of the German defences in detail. The authors also provide an overview of the development of German defences and changes in defensive doctrine – defence in depth and the ‘empty battlefield’ and the increasing power of artillery – which necessitated construction of increasingly strong concrete structures and the move to smaller, scattered, structures to provide protection against the weather and ‘ordinary’ enemy fire.

The second section of the book describes the various types of structure – including deep dugouts – their construction, maintenance and the difficulties posed by the high Flanders water table. The authors also describe the use of troops, PoWs (principally Russian) and civilian labour – mainly forced but also Belgian volunteers attracted by the high rates of pay. This is probably the most complex part of the book – a result of the volume of information containing complicated and unfamiliar names of German units and the system under which sections of soldiers seconded to a construction project would be renamed as if a separate unit.

The authors also cover the acquisition and delivery of the materials needed and demolish the myth that German concrete defences were constructed using British Portland cement imported through Holland. Finally, a short ‘Tours Section’ details bunkers that remain today, a glossary of German terms and a bibliography. The engineering drawings are excellent and the maps, though small, are detailed (most retain legibility when magnified). The many photographs are fascinating, although the decision to reproduce contemporary photographs in sepia seems to reduce detail. As acknowledged experts – and with Nigel Cave’s editing involvement and a decent translation from the original – the authors leave little to say about the subject and have delivered a readable book.

Niall Ferguson