From the Dardanelles to Dunkirk by Peter Hodgkinson and Andrew Rice

- Home

- World War I Book Reviews

- From the Dardanelles to Dunkirk by Peter Hodgkinson and Andrew Rice

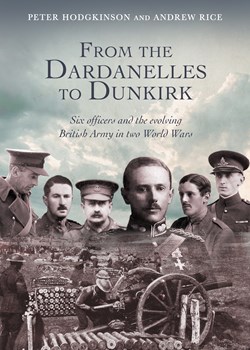

From the Dardanelles to Dunkirk

Peter Hodgkinson and Andrew Rice

Printed by Amazon, 2022.

299 pp. 19 photos, 8 maps. Bibliography.

ISBN 9798405428369.

This is an ambitious book which tells the story of six officers, all of the Rice family and spans 65 years (1887-1952) including two World Wars. It sets out to place each officer in the context of his own military unit and its operations and, in so doing, seeks to ‘examine the problems within the British officer corps during this period and how the army evolved, or struggled to evolve, in terms of its learning from conflict’. Quite an undertaking.

Fortunately, the two authors are well equipped to deal with this daunting project. Peter Hodgkinson has already written several books on the First World War and Andrew Rice is a relative of the officers concerned. Between them, they have produced a readable and informative account of military circumstances and personal experiences.

From the Dardanelles to Dunkirk is well worth reading.

Probably the most colourful, and certainly the most disreputable of the six Rice officers was Hugh who was commissioned, via the Militia, into the 1st Battalion Essex Regiment in 1888. Hugh was something of a philanderer. His marriage to the long-suffering Lydia failed and he produced an illegitimate child. Professionally, he was generally considered inadequate and was repeatedly absent from service because of illness. And yet, he was promoted Major in 1908 and served in Gallipoli and in France during the First World War ending his career as a Lieutenant Colonel. Just how he was able to continue as a serving officer when his reports, especially during the period before 1914, had consistently noted that he ‘had not the capacity for command’, is discussed at some length and illustrates both the military and social weaknesses of the Victorian/Edwardian army.

Hugh was the uncle of the five Rice brothers: Neil, Joe, Tommy, Dick and Edward. The book describes the military careers of each brother. Neil joined the Buffs (the East Kent Regiment), the only infantryman, and the other four became gunners. Undoubtedly, the most striking sections of From the Dardanelles to Dunkirk are those that feature the diary and letters of Joe. They make up half of the book and cover the period 1916-1918 when Joe was on the Western Front with the 82 Brigade RFA seeing action during the Somme, Passchendaele, the German Spring offensive and the Hundred Days. The extracts from the diary and letters are a pleasure to read. They cover technical and tactical issues: the direct and indirect laying of a gun; the difference between percussion and ‘time’ rounds and between HE and shrapnel; the use of a Clinometer; the process of ‘Registering’; the development of new techniques such as flash spotting, sound ranging, the use of Fuse 106; the tactical advances of the creeping barrage, the Chinese barrage and counter-battery work and the importance of the RFC as an artillery observer. There is considerable technical detail in the diary and letters, but they are brought to life by Joe’s humour and anecdotes. In August 1918 Joe wrote home, ‘I haven’t been able to get Edward (then aged 8) a Boche helmet. I picked up one of those peakless soft caps last night, but thought it was too smelly to bring back’. There were sad occasions, ‘on 18 September we were shelled from 05.15 to 06.45 and had to go on firing our guns all the time. We had ten casualties during that time (six killed). It was the worst hour and a half I ever had’. In contrast to Hugh, Joe was a keen and professional officer who took every opportunity for personal advancement and who liked to be in the thick of it. He ended the war with an MC and Bar and the Belgian Croix de Guerre.

Dick Rice also left a diary, but of a quite different kind. Dick was in France with the 48th Division in 1940 during the ‘phoney war’ and at Dunkirk. His diary is matter of fact and, although lacking Joe’s light touch, it adds much useful information to the Official War Diaries. It paints a depressing picture of an ill-prepared BEF and a French ally who had been out-thought by the Germans. In May 1940, Dick wrote of an incident that illustrated the general fiasco. A bridge in Belgium needed to be blown up. No fuses could be found. The French sappers had the necessary equipment, but refused to act without written authority from their General. The General could not be found. Many hours were lost. Dick survived Dunkirk but was killed by shell-fire in May 1943 while serving in North Africa.

The authors are successful in skillfully placing the operations that involved the six Rice officers in their military and social context and they use key sources to make the links between the various episodes seamless and illuminating. From the Dardanelles to Dunkirk could simply be a piece of family history for the benefit of future Rice generations, but it is more than that, it gives the interested reader an insight into past conflicts and related social conditions through the personal experiences of the six Rice officers: it is history at a family level.

There are a few quibbles: the book needs some careful editing because of spelling and typo mistakes; the maps reproduced from the British Official Histories are hardly readable; it needs an index, and, given the emphasis on artillery, there is no mention in the bibliography of Strong and Marble’s Artillery in the Great War, which must be one of the best books on the subject. Having said that, ‘From the Dardanelles to Dunkirk’ is a most enjoyable book and is thoroughly recommended.

Reviewed for The Western Front Association by Michael Senior (February 2022)