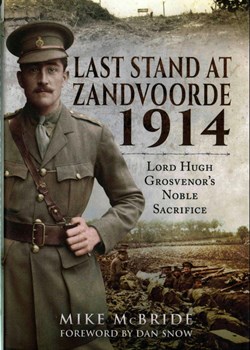

Last Stand at Zandvoorde 1914: Lord Hugh Grosvenor’s Noble Sacrifice

- Home

- World War I Book Reviews

- Last Stand at Zandvoorde 1914: Lord Hugh Grosvenor’s Noble Sacrifice

By Mike McBride

Pen and Sword Barnsley £19.99, 234pp, ills in page throughout, bibliog, ISBN 1473891574.

Review by David J Filsell

Whilst there is a very strong case for a serious study of the loss of Zandvoorde on 30th October 1914, in my judgement Last stand at Zandvoorde 1914 is not it. My concerns were first triggered by the book’s foreword by the ubiquitous ‘military historian’, Dan Snow. ‘The terrible fighting in the autumn of 1914 is often is often overlooked’. Really Dan? By whom? You can fill shelves with books on the topic.

While, and acceptably, Last stand at Zandvoorde is a work which leans on previous writing, unacceptably it also lacks a single note or reference. It is also a book which seems to lack sufficient knowledge of recent thinking and writing about British Army of 1914. Rather, it tiredly rehearses the value of the aristocratic and public ethos of its officer corps and the sheer bloody mindedness of its ‘regulars’, and fails to the note the distillation of the army’s skills in 1914 by the extremely high numbers of reservists in the BEF’s ranks.

Apart from its somewhat misleading chronology, loss of faith in the book became complete in the author’s employment of the American term First Lieutenant and, finally, its placement of the Worcestershire’s famous action at Gheluvelt on October 31st 1914 as having taken place on October 29th, the day Zandvoorde was lost. Indeed pressure at Gheluvelt here seems to be deployed as partially responsible for the loss of Zandvoorde itself. It was not.

Nor was action at Zandvoorde, as author describes it, an encounter battle. It was an expected overwhelming assault on weak, fixed and inadequately supported positions manned by exhausted British cavalry (making shift for infantry). The British trenches were on ill chosen forward slopes - its machine guns poorly deployed, and the position overwhelmed by German artillery and a strong infantry assault.

The British lost the village, but it was taken at a cost which destroyed German initiative, command and control. As at Gheluvelt the next day, the Germans failed to break through to assault Ypres (Unexamined here is the speed and effectiveness with which Haig and his Chief of staff, ‘Johnny’ Gough reacted to the loss of Zandvoorde. So speedy and effective were their measures that an effective stop line - some six battalions strong - was created that the timid German advance was halted.)

Finally, and sadly, whilst the previously unpublished letters of Lord Hugh Grosvenor, who died at Zandvoorde, punctuate this work, they add little of real value. In the main, and understandably, they are no more interesting than the vast majority of letters sent hom from the lines by soldiers suffering the discomforts, dangers and fears of war.

Sadly, what remains true is that the failed defence of British Zandvoorde has still never been adequately analysed in print. My belief is that it cannot be other since survivors of the action were remarkably few, the fog of to war dense, and remaining limited records unclear.

Why do I care that this story is not better told? Flanking the cavalry at Zandvoorde were 1st Battalion Royal Welsh Fusiliers (in positions that the commanding officer judged suicidal - and was pressed to protest). Its positions were taken in front, flank, from Zandvoorde, and, probably, rear. The battalion was destroyed in detail. Amongst those killed were its commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Henry Cadogan and almost all of lower rank. One was Private Albert Filsell. Neither he nor his commanding officer have known graves.