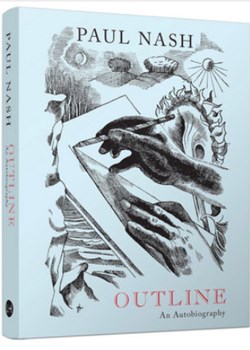

Outline. An Autobiography. Paul Nash.

- Home

- World War I Book Reviews

- Outline. An Autobiography. Paul Nash.

Hardback, 280 pages

14 Colour illustrations

9 Black and White illustrations

Published 16 October 2016

Edited by David Boyd Haycock.

Written by Paul Nash and Margaret Nash.

Oultine is four books in one. The first part is an autobiography, the second part are the notes Nash compiled to complete his autobiography, the third part are letters home to his wife while on the Western Front near Ypres in 1917 and the fourth part is a biography that completes Nash’s life, written by his wife.

The autobiography is as good as his art, and his art is masterful. Within a few sentences you realise you are reading an author of talent. You later learn that his qualities as a writer were recognised when tentatively he became an art critic; only to be crushed by jealous and vitriolic established critics who appear to have wanted to kill off that most dangerous of voices - a critic who was a talented artist too.

Nash's love of the countryside is established in his youth.

"I realised, without expressing the thought, that I belonged to the country. The mere sight of it disturbed my senses. Its scenes, and sounds, and smells intoxicated me anew." Paul Nash, Outlines p.36

I read books in print and e-Books. I am used to tagging pages and highlighting passages. With e-Books this is a tap or a swipe of the finger, in a hardback book like this one I use Post-It Note Index and Arrow tabs: I got through a pack of 120 in the 145 pages that make up the autobiography. This is evidence enough for me how worthwhile the book is to own.

On just about every page there is a line to savour, an image or view described to read through several times to get it in your mind’s eye, a sound recalled to hear perfectly and clearly, an anecdote to quote, a phrase, thought or reflection on life to be reminded of. You can sense how his artist’s mind developed and worked, whether filling a page with images or words. Paul Nash thinks a thing through with meticulous care and thought. He is an author to enjoy, and a life to study should you know someone with ambitions to be a ‘creative’: he found his way, he took his chances, he developed resolve, he made art pay (just), he believed in what he had to say and show, while circumstances saw him tipped out of the chalk downlands of southern Britain, into the torturted hell of the Ypres Salient in 1917.

People like his grandfather and uncle Hubert are such rounded characters, so well described, that you can see them: an artist could draw them and create a likeness. Nash describes his uncle:

"He was a tremendous specimen of a man, tall and powerfully built with a handsome head hewn out in Gladstonian lineaments".

In relation to the First World War, always asking myself the question, ‘what was it really like?’ having been fed, at length and repeatedly over several decades the stories of my late grandfather (a machine-gunner who served on the Somme in 1916 and at Third Ypres in 1917) I came to feel that Paul Nash said it for me; that paintings such as ‘The Menin Road’ got closest to taking me there. Reading Paul Nash’s own words, studying his work further, then attending the new exhibition at Tate Britain, confirms this and more: both as a writer and an artist, his affinity with, study of, and mastery of what his own mind saw does what not photograph can achieve - it recreates ‘the mind’s eye’ - Paul Nash put on paper and canvas what his mind re-created. We see the world translated. We sense it better for this. We begin to 'feel' it.

Margaret Nash descibes what Paul made of joining the Artist's Rifles in 1914.

"He was thrilled with a boyish pride in the whole heroic adventure of war. He saw its ugliness, but he also saw its haunting beauty and drama ... beauty and mystery."

You will reach page 145, turn to the next page and despair. Paul Nash wrote no more - war is yet to break out. He takes us towards August 1914, but no further, not in his autobiography at least. He was writing from notes made in the 1930s and this is 1946; he died suddenly.

Having been so engaged, so entralled and so convinced of the world he recreated for us: growing up, facing many boyhood struggles at school - when and where attempts were made to bash him into something he could never be (a naval officer), and seeing, hearing and sensing it all so well: eventually gravitating towards his place as a graphic designer, or illustrator, or landscape artist, and then learning how he would go off somewhere, seak out the view, and having drawn it at the time, then, many years later writing about it from the artist’s point of view, picking out the detail that matters when forming a picture. Having done all this, at first you will feel you have walked up to the edge of a great chasm.

Can you read on after page 145?

‘Paul Nash’s Notes For The Continuation of His Autobiography’ only tell you how much thought he took when preparing his text. The previous 145 pages are not, could not have been, a stiring ‘stream of consciousness’ to have come out so well. Here are the writer’s preparatory notes. It is hard to imagine how he would have filled the pages, only to know that 27 points would have been transformed into another 145 pages. A glance through his notes, and already knowing him as an artist inclined to detail, that like Proust, given a chance, his autobiography would have gone on to many hundreds of pages, and several volumes.

You quickly wonder about the rest of the book. There follow around 30 pages of letters from Paul Nash to his wife, 1917-18. These go a long way to bring relief from your sense of loss and missed opportunity. In a way, it is charming and revealing to hear Paul Nash writing in a less indulgent and studious way. The same voice is there, while his love for his wife Margaret emerges, as does the tone of a journalist - he knows how to tell a story, make a point, paint a picture and to recreate a scene, as well as any artist or screenwriter. Some of his War Work, paintings from the Western Front, are featured too. Quite quickly you understand what he has achieved: it is if a young man, after ten years perfecting his eye on the human body, has been presented with the body distressed: the skin torn off, bones broken and exposed … he would understand the comparison. His approach, as he and others saw it, was to ‘animate nature’ - to see trees as ‘personages’ as it is put. This thought alone explains his shell-struck trees on the Western Front as surreal, dripping and drooping, as if made of flesh like molten pulp. Only a master of the natural and imagined landscape could realise it thus.

As if you are taking a few steps out of a hole, depressed at having lost Paul Nash’s voice for the part of the his life that might interest you most - his war experiences, his wife Margaret Nash steps in to complete her husband’s story 1913-1946.

Margaret was smart. She had gained a scholarship to Oxford and had been working in Whitehall when they met. She tells it well.

On completing the book, by chance, I was coming into London last Sunday morning (6th November) and decided to take myself to Tate Britain to see the recently opened Paul Nash exhibition. I wasn’t disappointed. ‘Outline’ had prepared my way beautifully.

I felt I knew much of the work in Room 1 seeing many of his early drawings and paintings, while Room 2 enjoying his First World War work, which was even more powerful than I had imagined. Neither a reproduction in a book, nor online, can do justice to any painting, but here the scale of ‘Menin Road’ is incredible. It is a piece of theatre painted on a large canvas (182.8 x 317.5). That’s nearly 6ft high, and remember it is already mounted at knee height. It is over 10ft long. It shocking, memorable and appropriate.

"On looking at his work at this period," Margaret Nash writes, "one realises the immense importance of its line and plan, but I think that that formal aspect of his work came from a sudden unnaccustomed acceptance of a highly disciplined life in order to meet something that had hitherto never come into his experience - fear, danger, death and that experience included himself and me." Outline. p197.

Armed with an audio-guide, I initially crossed back and forth between these two rooms. You see that Paul Nash's mind, that was mastering his artistic interpretation of the natural landscape, is well able to visualise the flip-side hell of a landscape destroyed by artillery and poison gas, lit up by Verey lights and punctured by steel, wrapped in tangles of barbed wire with trees, as already described … not quite as dead as a photograph might show them. It is as if the sap they drip has been drawn from the puckered earth and made them like black candles. They are, and are meant to be, totems to the dead who have been churned into the battlefield.

The following five rooms of art take us through another thirty years, and another five stages in his life. I’ll leave you to explore these rooms and discover this part of Paul Nash’s life for yourself, however, it is worth noting that having been an Official War Artist in the First World War, that Paul Nash was commissioned to paint the Second World War too. ‘Totes Meer’ (Dead Sea) with broken parts of downed German bombers forming a sea breaking on a British Shore has its origins in the young Paul Nash. There is a clear logic, that I'd never appreciate before, between his early work, his experiences on the Western Front, surrealism and his later work.

Oultine. An Autobiography is a remarkable book that pieces together an author and painter who captured the pain suffered by ‘Mother Earth’ during the First World War; for me he gets as close as I have ever seen or experienced of ‘being there’ in the mud of the Ypres Salient in 1917.

Oultine. An Autobiograph. Paul Nash (and Margaret Nash, with forewards/introductions by David Boyd Haycock) A must for those with an interest an ‘artist as a young man’ (in his own words), as well as British art and times of 1900 through the Great War, Surrealism, World War 2 and a little beyond.

Find out more about Paul Nash on the Tate Britain website.

Purchase 'Outline' from Lund Humphries.

Purchase 'Paul Nash' from Tate Shop

Review by Jonathan Vernon