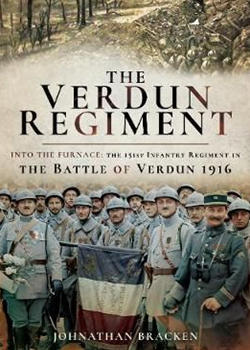

The Verdun Regiment. Into the Furnace: The 151st Infantry Regiment in the Battle of Verdun 1916

- Home

- World War I Book Reviews

- The Verdun Regiment. Into the Furnace: The 151st Infantry Regiment in the Battle of Verdun 1916

By Johnathan Bracken

Pen & Sword, £25.00, 269pp, hb, 30 ills, maps, notes, refs, bibliog and index.

ISBN: 978–152–671–029–1

The author is the president of a living history organisation dedicated to the French 151st Infantry whose home garrison was Verdun. Diverted from its annual summer manoeuvres several days before war was declared, the 151st’s service began on 31 July 1914 when, with regimental colours flying and the band playing, it marched out to defend the French frontier.

Three weeks later its first contact with the enemy in the Battle of the Frontiers resulted in over 800 casualties. Another 600 officers and men fell in the Battle of the Marne and then there was the Yser, the Argonne Forest, the Second Battle of Champagne and, in 1916, Verdun.

However, it is the regiment’s six rotations at Verdun that form the main part of the book and where the author comes into his own. Drawing closely on published and unpublished memoirs and war diaries he paints a graphic picture of its actions and of conditions both at the front and at the rear.

In addition to an interesting, although frequently distressing chapter on various shell types and their – generally – cheerful nicknames wholly at odds with from their effects, there is plenty of detail about the equipment normally carried by the long–suffering poilu which provides a detailed picture of the 151st’s service. Readers with an interest in the Battle of Verdun will not find better evocations of what it was like to serve there than this book and it is pleasing that the ‘ordinary men’ who fought at Verdun have been remembered and their sacrifice acknowledged.

Apart from the very rare error, such as placing the 72nd Infantry Division on the Left Bank in March 1916 when it was actually on the Right Bank with the 51st, the maps are disappointing. While the author clearly has the terrain firmly fixed in his head and knows what he means when he refers to this ravine or that trench, for the ordinary reader such a lot of place names without an adequate accompanying map can be irritating and tiresome. They cover only part of the regiment’s service, which could be better studied if placed in the relevant chapters, rather than grouped at the start of the book. Equally, complicated maps – like those dealing with the fighting on the Mort–Homme in May 1916, where the trenches were often very close together – would benefit from clearer distinction between the German and French positions than in grey and black. However, this does not detract from the overall quality of the work, which combines readability with detailed knowledge and great descriptive power. It is warmly recommended.

Christina Holstein